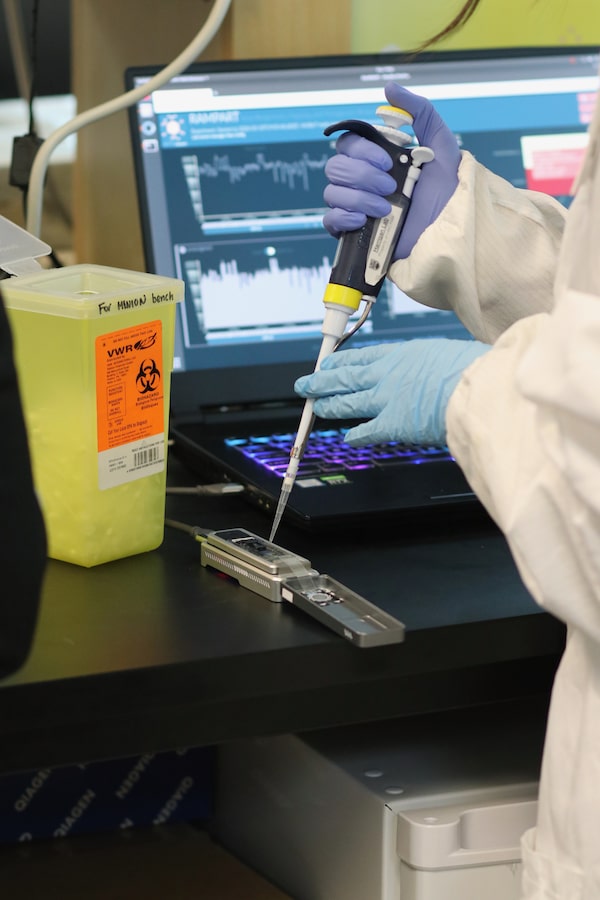

Since the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in B.C. one year ago, scientists at the BCCDC were able to pull apart the genetic blueprint of the virus.Michael Donoghue/BC Centre for Disease Control

B.C.’s biotechnology sector has emerged as a critical arm of the province’s pandemic response. As a result, this has been a rare year where funding and resources are not in question.

In the coming days, the B.C. Centre for Disease Control aims to increase its surveillance to screen every new COVID-19-positive sample for the presence of those variants of the coronavirus that are alarming public-health officials around the globe.

Where the variant is flagged, the sample will then be run through the process of whole genome sequencing – a complex and time-consuming technique to determine the genetic makeup of COVID-19. Sequencing allows scientists to identify where the virus is coming from, how it is spreading and when it is mutating.

When the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in British Columbia one year ago, scientists at the BCCDC were already prepared to take the first swab and analyze the virus’s genetic information. The capacity to do this work is the legacy of 20 years of private and publicly funded research in the province, and it has guided Bonnie Henry, Provincial Health Officer, through a year of wrenching decisions over opening schools, closing borders and more.

“From the very beginning, genome sequencing helped us understand how the virus is travelling,” Dr. Henry said in an interview. She recalled the fateful telephone call from Mel Krajden, the medical director of the public-health laboratory at the BCCDC, confirming the arrival of COVID-19 in B.C. late in January, 2020. Dr. Krajden’s team was able to match their data to the first genome blueprint that had been released by China on Jan. 10. “It established our need to step up our response,” Dr. Henry said.

Public-health officials began this year with an ambitious plan to vaccinate 4.3 million British Columbians by the end of the summer, laying out the order of when each resident can get in line. The detection in January of what public health refers to as “variants of concern” may reshape that plan.

There are thousands of genetically distinct branches of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The variants of concern are ones that have the power to transmit between people more easily – possibly bringing more serious illness. On Friday, health officials reported they have found a total of 28 cases – a small number, but troubling because contact tracing has not been able to determine how all of those cases arrived here.

The data released on Friday show encouraging progress in slowing the pandemic in B.C., but Dr. Henry said she is not ready to roll back restrictions just yet. “We need to buy time to understand whether these variants of concern are going to affect transmission in our community.”

When B.C. Premier John Horgan pressed Ottawa last spring to close the U.S. border for non-essential travel, he was able to point to the BCCDC’s research to justify his request. “What we were finding was that cases were clustering, they were essentially from Washington State,” Dr. Henry said. “This was at the point where we needed to make decisions about what we were going to do in early March. … We needed to do things differently, and stopping travel was the first thing.”

The province closed schools last spring, and when classes resumed in September, Dr. Henry was at odds with the B.C. teachers’ union and some parent organizations over safety in the classroom. Her certainty over concerns about school transmissions was based, again, on her data. And on Friday she released the latest data to show that school-aged children, despite the reopening, remain at low risk. COVID-19 transmission in B.C. is largely driven by those at the ages of 20 to 49.

“What genomics does, it offers an amazing tool to create evidence to support these decisions,” said Pascal Spothelfer, president and chief executive officer of Genome BC.

The capacity for genome sequencing at the BCCDC is funded by Genome BC, which was launched in 2000 as a virtual research institute. It doesn’t run its own facilities or hire its own scientists, rather it corrals and funds existing research science resources.

This year, funding for research is flowing. But it is only by good fortune that B.C. had the infrastructure in place. When there is no obvious health crisis, Dr. Henry noted, it is harder to maintain the funding for such research. “They’ve been whittled away – as all public health has over the years – but we’ve been fighting to keep this core of our public-health lab going. We’d be lost without them.”

Dr. Natalie Prystajecky, program head for the environmental microbiology program at the BCCDC Public Health Laboratory, says her team plans to continue to monitor the spread of the virus after most adults are vaccinated.Michael Donoghue/BC Centre for Disease Control

Natalie Prystajecky is the program head for the environmental microbiology program at the BCCDC Public Health Laboratory and specializes in genome sequencing.

“Last year at this time, we were working around the clock to generate a diagnostic test to detect [COVID-19],” she said. “It was to the wire that we actually got the test ready for the first case, and around that time we decided, if we do find one, we should sequence that.”

Initially the sequencing was regarded as research, but by last summer, it had become a routine clinical test, helping health officials understand outbreaks and transmission. Her lab can now produce 750 genome sequences every week, but they are working flat out and need to do more.

A year into this, Dr. Prystajecky sees relentless demand for this kind of bioinformatic surveillance ahead. Even as B.C. hopes to have most adults vaccinated by the fall, she said her team will still be monitoring to see if people are still at risk as the virus continues to mutate.

“I think that when we look back a year ago, we didn’t really expect to be here today, but as microbiologists and public-health practitioners, we’ve been training for this sort of thing for a whole life. This is what we’re meant to do.”

Michael Donoghue/BC Centre for Disease Control

We have a weekly Western Canada newsletter written by our B.C. and Alberta bureau chiefs, providing a comprehensive package of the news you need to know about the region and its place in the issues facing Canada. Sign up today.

Justine Hunter

Justine Hunter