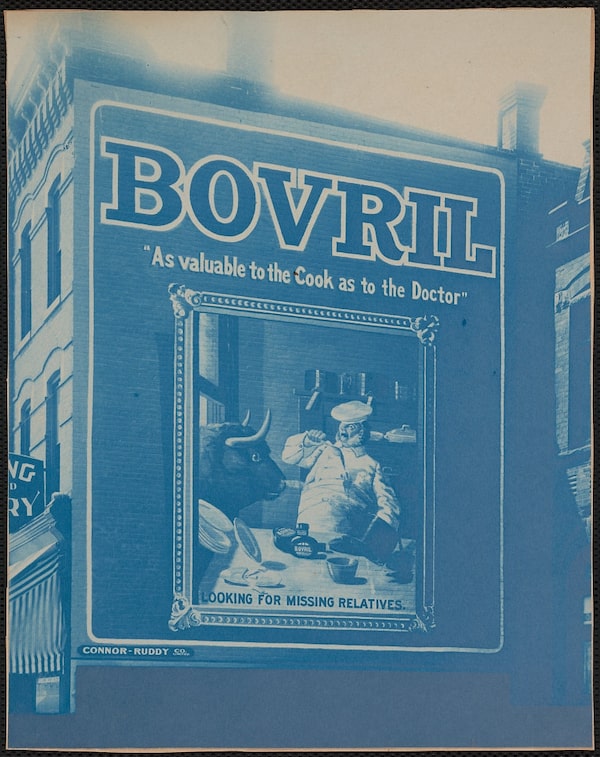

Toronto, 1906: Signs for Tona-Cola, Bovril and hand-made watches stand on a building opposite Old City Hall. Connor-Ruddy, an outdoor ad company later renamed E.L. Ruddy, monetized the vacant lots and blank walls of the city with carefully painted billboards like these.Photography: E.L. Ruddy Company Ltd./City of Toronto Archives

For more than half a century, the wind, rain and snow have clawed at a painted sign high on a brick wall overlooking Richmond Street West. The black-and-white serif lettering has weathered and flaked away in patches, but its message is still just legible:

GELBER BROS. LIMITED. WHOLESALE WOOLENS AND DRESS GOODS.

The Gelber Bros. sign is just one of dozens of ghost signs that are hiding in plain sight around Toronto. These old hand-painted advertisements and company logos, often applied to the exterior wall of buildings, were a popular way to drive up sales before the rise of cheap printed posters and radio and TV commercials.

Each one is a relic from the city’s past that tells a small but important piece of a bigger story about how Torontonians used to live: the food they ate (and the salty condiments they seasoned with), the groceries they bought and the clothes they wore.

The Gelber Bros. textile company was founded by Louis and Moses Gelber, who arrived as teens from what was then Austria in 1896. Louis spent time as a travelling entrepreneur in Eastern Ontario before finding success with his brother in the early 1900s. In 1912, their company built the Gelber Building, that now bears their fading sign and, in 1932, added a warehouse next door on Richmond Street.

For a time, Gelber Bros. was a major player in the Toronto garment industry and it made the family wealthy and influential. Their children grew up to become prominent diplomats, politicians, philanthropists, lawyers and doctors before the business faded out like its sign.

In his novel Consolation, author Michael Redhill conjures the painting of the Gelber Bros. sign in a passage about the building of Toronto. “…[W]e have seen that sign since we were children, we have watched it slowly fade – the brick rising through the skin of the weathered paint like a welt – and although we do not know the name of the man who put those words there, and surely he is dead, we cannot doubt that he lived, he lived here, he worked here, he was a Torontonian.”

Before printed posters and illuminated advertisements, painted signs were ubiquitous in Toronto. The outdoor advertising company Connor-Ruddy (later renamed E.L. Ruddy) made a fortune monetizing blank brick walls and filling vacant lots with billboards.

Businesses big and small barked commands from practically every wall and rooftop: DRINK LIPTON TEA. CHEW WRIGLEY’S GUM. BUY UNION-MADE SHOES.

In 1906, the company printed a scrapbook of blue-tinted cyanotype photographs that proudly displayed its work for companies such as Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce, Sweet Caporal cigarettes, President Suspenders and Wampole’s Formolid Cream – “sweetens and purifies the breath, and keeps the teeth sound and pearly.”

Samples from Connor-Ruddy's cyanotype photo book show some of its billboards across Toronto. At right is the Connor-Ruddy lot at 835 Yonge St., with painters at work on sections of wooden board.

'Looking for missing relatives,' reads the caption on one Bovril ad in which a chef making the meat-based beverage is intruded upon by a cow.

Ruddy had a yard at Yonge and Church Streets where artists painted gigantic billboards on sections of wooden board that were later assembled on site.

Working on a scaffold, those same artists were also skilled enough to render company logos and fonts in exquisite detail on the rough brick of a building exterior.

One particularly intricate work by the company advertised the beef extract Bovril with a painting of a chef recoiling in horror at a cow bursting through his kitchen window. The caption reads: LOOKING FOR MISSING RELATIVES.

No matter how creative and skilled, the explosion of outdoor advertising in the first half of the 20th century in cities across North America was deeply unpopular with urban reform groups such as those associated with the popular City Beautiful movement.

“Cities spend tens and hundreds of thousands for beautiful buildings, for parks and parkways and playgrounds, and then allow the bill-poster to use them as a background for his flaming advertisements,” complained Pittsburgh politician Clinton Rogers Woodruff in the January, 1908, issue of The Craftsman.

In Toronto, the Guild of Civic Art pushed the city government to restrict outdoor advertising and keep it away from beauty spots such as parks. Like tangled telephone wires and the problem of stray dogs, all ads were considered tacky monstrosities that diminished the city’s grandeur.

A Globe article from July 13, 1912, reports on citizen's complaints about the profusion of billboards in Toronto.

Despite their protestations and laws restricting size and “indecent” or “objectionable” content, outdoor advertising continued to spread. In 1912, The Globe and Mail reported on what it called the “signboard plague” sweeping the city. “In almost every section [of Toronto] where there is any vacant land, the billboard rears its ugly head.”

To survive into old age, a painted advertisement must be lucky, perhaps located on the leeward side of a building or hidden beneath siding. The best-preserved examples are usually to be found on an old exterior wall after the demolition of a neighbouring building, such as the Quaker Oats sign at the Honest Ed’s site.

For all the ghost signs exposed and vanishing in Toronto, there are many more still hidden, waiting to be revealed. Around 1906, Connor-Ruddy covered the east wall of the Nealon Hotel at 197 King St. East with a display for Old Dutch cleaner. In later years, the same wall advertised Liptons Tea and Wrigley’s chewing gum.

A billboard on the side of the Nealon Hotel on King Street.

In the 1980s, a new residential building at the corner of King and Frederick Streets obscured the wall and its advertising, which at the time was a faded display for Coca-Cola. Peering into the gap between the buildings today shows plenty of cyan paint still adhered to the wall – fraying historical threads that will one day be gone.

The Gelber Bros. sign owes some of its longevity to being covered. As recently as April, 2007, a vinyl advertisement for Red Stripe lager obscured the sign from view and protected it from damage.

Those left to the elements sometimes give way to older advertisements beneath. At 345 Adelaide St. West, a painted sign for trade journal publisher Hugh C. MacLean is slowly resurfacing from under a newer ad for the camera company Gevaert. Like a slow movie cross-fade, the old MacLean sign gets clearer each year as the Gevaert paint slowly flakes away.

Editor’s note: A photo caption in an earlier version of this story misidentified a sign for Tona-Cola, a Coca-Cola imitation beverage, as a sign for Coca-Cola. This version has been corrected.