As part of The Globe’s move to a new building next year, many dusty old files are being assessed. What do you save for history, and what is tossed?

I was asked this week to evaluate four banker’s boxes filled with folders from the sixties and seventies, a trove of journalistic treasure: stories and photos from the Peking (that’s what it was called then) bureau. And, yes, the plan is to preserve and perhaps display this trove in some manner. It’s a snapshot of how much (and, in some cases, how little) journalism has changed.

I was struck most by a few folders labelled “Ping-Pong.” In 1971, in the midst of the Cold War, the American table-tennis team received a surprise invitation to play in the People’s Republic of China. The first official visit since the 1950s to what was then a closed, even secretive Communist country, the tournament remembered as “Ping-Pong diplomacy” changed the course of history. It broke China’s deeply hostile relationship with the United States, and led to the momentous visit by President Richard Nixon the following year.

At the time, only three members of the Western media were based in China, and only one worked for an English-language newspaper: The Globe and Mail.

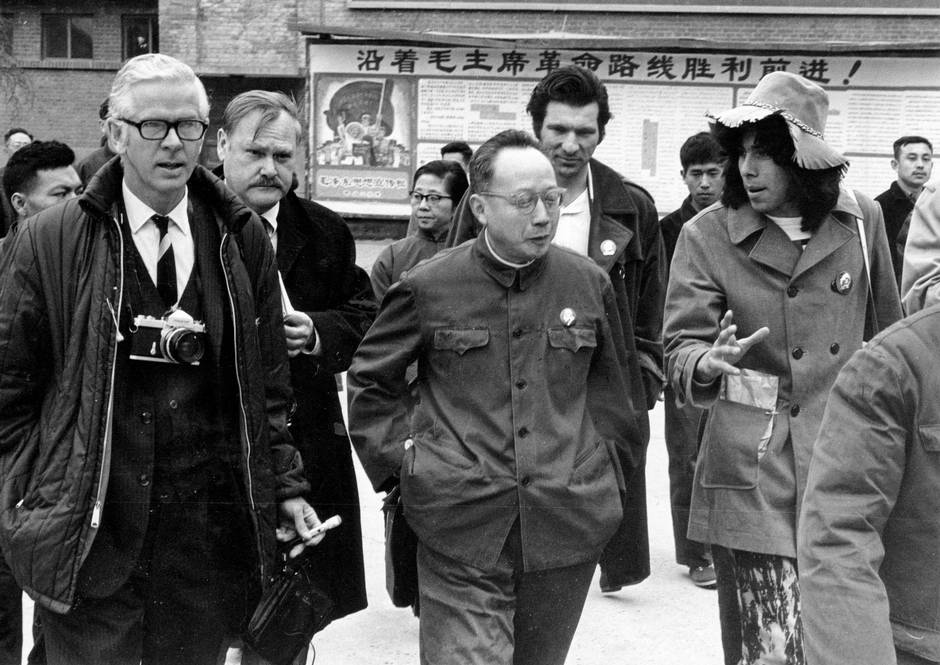

I showed the files to the China correspondent of the day, Norman Webster, later to become editor-in-chief of both The Globe and The Montreal Gazette. He recalls that he was in Hong Kong with his family on a break when he got word that the tournament was on. He met the U.S. team and returned with it to China. A contingent of reporters from Hong Kong also rushed in.

In those days, it was hard to be a foreign correspondent if you weren’t also a great observer of people and trends, knowledgeable about history and a brilliant writer. That’s because, especially in a secretive country where few spoke English, you couldn’t research online or just ask for help. Communication with your editor took at least two days, so few changes could be made once your copy was sent. A few quotes from the historic article:

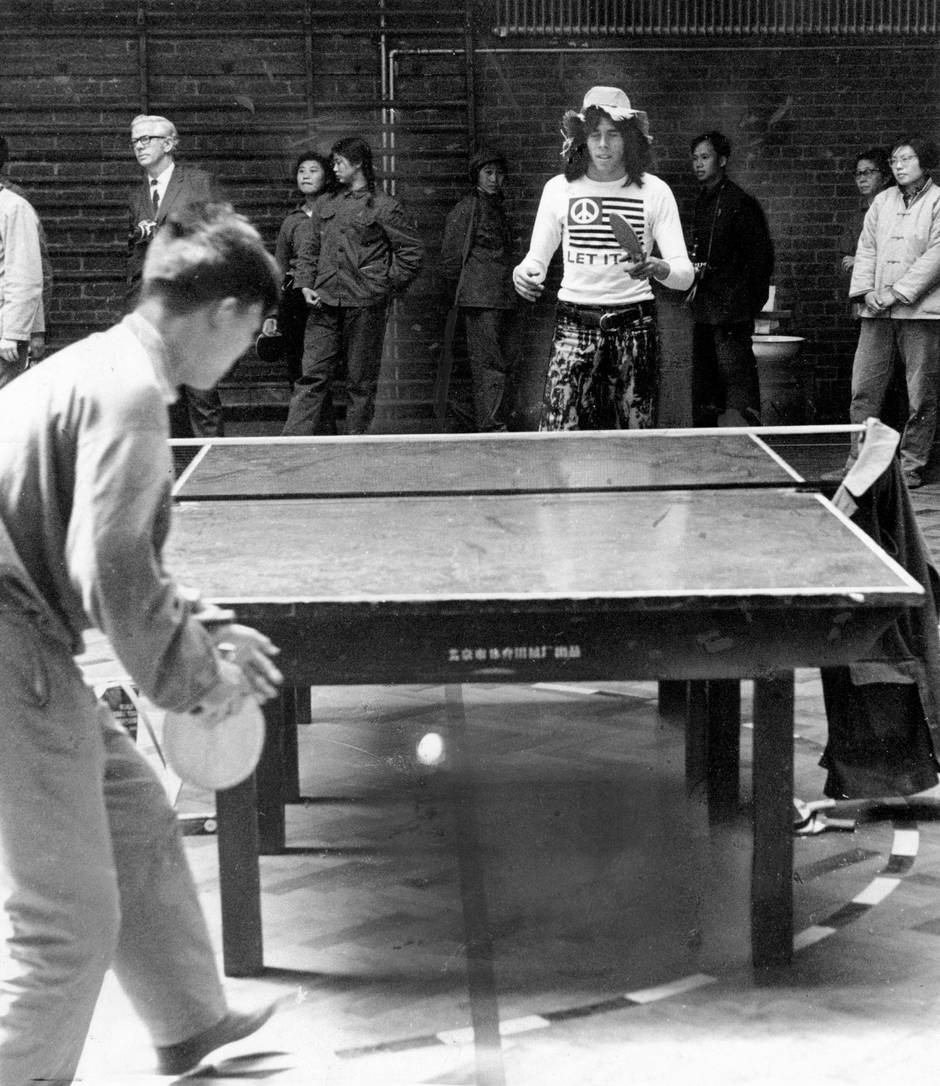

“China received its first U.S. delegation in more than two decades, and the smile on the face of the dragon was dazzling. … Most striking member of the party was 19-year-old Glen Cowan in purple bell bottoms, flowered shirt and Mao badge, with brown hair tumbling softly down to his shoulders. He provided a severe test for Oriental inscrutability.”

Getting that story and his photos out to a waiting world required logistics, skill and luck – and being first with a world exclusive was as important then as it is now. Mr. Webster explains that he would ride his bicycle to the cable office and type out his story in a cold and miserable building with perhaps a dozen suspicious locals watching every keystroke. The photos were more complicated. The film, along with long explanations typed on very thin paper, was sent by air.

The visiting reporters said they planned to send their photos of the event through Canton and then Hong Kong. Mr. Webster, with two years’ experience working in China, knew that route was unpredictable, and suggested they use his. He preferred to send photos from Shanghai via either Dhaka (then called Dacca) or Karachi to Paris and then by air cargo to Toronto. The others stuck to Hong Kong, and Mr. Webster’s photos arrived first, were published in The Globe and promptly sold to at least 18 publications around the world.

You can read all about those logistics in today’s dusty files with dozens of telegrams from broadcast media wanting to interview Mr. Webster, telegrams clarifying photo captions, consignment numbers from various airlines with emergency contact numbers for the most senior editors. Here’s one of the telegrams: “Small wood box with twelve undeveloped films airfreighted Peking to go via Air France Shanghai Stop.” Today, you’d take a photo, check the facts online, write the story and hit “send.”

“I’m jealous,” Mr. Webster says, comparing journalism then and now. “You had to have a lot in your head. You had to study before you left [Canada]. No one spoke English then and you couldn’t trust the government propaganda. So you had to observe and write about what you saw.” Or didn’t see: “like Mao being out of sight for months.”

It shows just how difficult journalism could be, when back in Canada, most reporters had no trouble with language, finding sources of information and paper records. On the upside, you were more likely to have the luxury of time to think and craft your writing. Today, the competition is so much broader, the scrutiny on the facts much greater.

What prevails is the need to tell compelling stories in an interesting way – and, yes, to be first.

UPDATE (SEPTEMBER 29, 2015):

A former editor, Wilf Slater wrote to me on the weekend explaining how tense and exciting it was in the newsroom in 1971 when then China correspondent Norman Webster broke the ping pong diplomacy story and the first photos were shared by The Globe with the world.

“I was assigned to track the package of film. It did travel via Shanghai, Paris and Montreal with DHL Courier.

Although it was a frustrating exercise at times it enhanced The Globe's reputation as a world class newspaper.

Canadian Pacific Airlines was the carrier and when the package arrived in Montreal I arranged with CP to entrust the package with the pilot or co-pilot to expedite its transfer.

Customs at the airport were alerted and the Globe's customs broker stood by to except its release. When customs called to report its arrival the agent said:"I have nine rolls of film, each three feet long." I was not amused and told him so.

The broker dispatched the package via a cab and there was excitement - and relief in the newsroom.

The darkroom staff was poised and had to fight off interlopers anxious to see the prints. TIME magazine arranged for its photo editor and an editor to examine contacts first hand and be the first outsiders to obtain prints. The editor was Ted Bolwell who had been associated with Globe Magazine.

The 18 newspapers noted received regular dispatches from China which were overseen by Eddie Phelan, an assistant managing editor. The newspapers from my aging memory include The New York Times, Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post.

Another Chinese story involved the death of Mao Tse-Tung. The correspondent at the time, H. Ross Munro, was not in the capital when the death was announced. He could not call Toronto from where he was located, but managed to get in touch with a British correspondent in Peking who took Munro's dictation and then dispatched the article to The Globe.

In the early days of China coverage telephone calls were relayed via San Francisco. On one occasion, Eldon Stonehouse, on rewrite, was told by the U.S. operator that she could not accept his request because"the United States does not recognize China". I do not remember whether the issue was resolved with another operator, but the link eventually become available.