Your mother was right: Money isn’t everything. New research that examines levels of life satisfaction across more than 1,200 Canadian neighbourhoods shows that big pay cheques don’t have much to say about the overall sense of happiness in a community.

What matters more are factors such as affordable homes, short commuting times and - most important - a sense of community belonging. In general, rural residents are happier than their urban counterparts, despite lower incomes, according to the study conducted by John Helliwell and Hugh Shiplett of the University of British Columbia and Christopher Barrington-Leigh of McGill University.

“Incomes used to be thought of as the primary source and determinant of happiness, but it’s clear that’s not the case,” Prof. Helliwell says. “It’s important to be able to feed yourself and provide yourself with necessities, but beyond a certain point, a higher income doesn’t stack up to having good friends and family nearby.”

While the researchers stop short of deriving lifestyle recommendations from their research, it’s hard not to be struck by the gap between the stratospheric cost of housing in Vancouver and Toronto and the uninspiring levels of happiness in those cities. Based upon the growing body of happiness research, anyone setting out in search of the good life may want to look elsewhere than Canada’s hottest real estate markets.

Toronto and Vancouver ranked at the very bottom of Canadian cities in a 2015 happiness ranking from Statistics Canada. The report drew on responses to the Canadian Community Health Survey and General Social Survey to calculate life satisfaction in 33 census metropolitan regions across the country. Calgary, Halifax, Montreal and Saskatoon all did better than Toronto and Vancouver, but the happiest cities of all were Saguenay, Que., Trois-Rivières, Que., St. John’s, Nfld., and Sudbury, Ont.

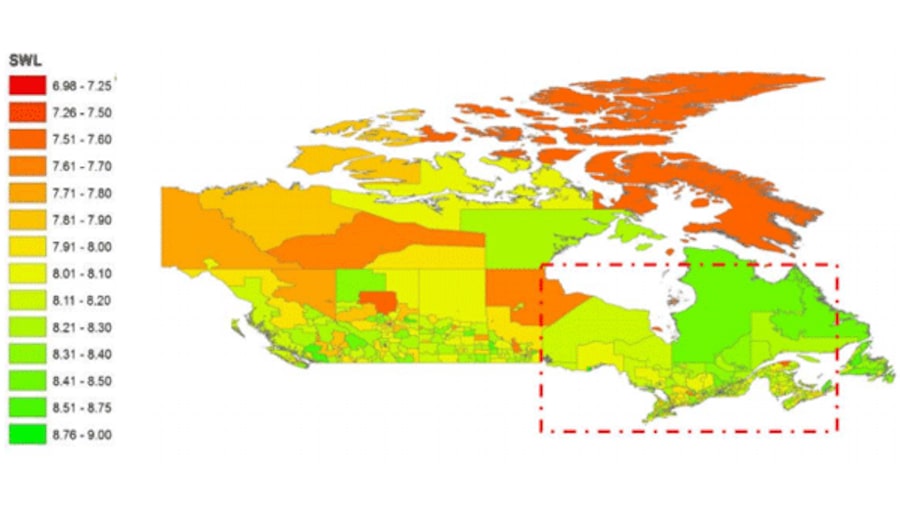

The new study, released as a working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research, is partly based on the same survey sources as the 2015 paper but offers a much finer-grained analysis. It splits Canada into 1,215 areas, most composed of 10,000 to 50,000 people. Prof. Helliwell and his co-authors used census boundaries and administrative borders, as well as geographical and man-made features, to arrive at these compact groupings. Their goal was to allow decision makers to track happiness at a local level, in keeping with what most people would naturally think of as neighborhoods or communities.

“We knew from earlier work that cities were systematically less happy than rural regions,” Prof. Helliwell says. “Now we’ve split up the cities and discovered there’s an astonishing range of neighborhood-level happiness within each city. Some of the happiest city neighborhoods are almost as happy as the happiest regions in rural areas.”

In Toronto, for instance, the happiest neighborhood is a swath of the city’s midtown, encompassing posh neighborhoods such as Rosedale, Leaside and Moore Park. It scores 8.26 on the 10-point scale used in the study. But even this unusually blissful urban patch fails to achieve the life satisfaction achieved by Canada’s cheeriest places – rustic communities such as Hope, B.C. (8.62), Souris, PEI (8.58) or Neebing, Ont. (8.94), where incomes may be not be as high as in Toronto but people generally seem more content.

To be sure, the rankings should be taken with a grain of salt. By international standards, most parts of Canada qualify as relatively happy, and so it’s hard to imagine a swarm of affluent Torontonians suddenly fleeing to Neebing in search of a better life. The authors also caution that their happiness numbers, based on data collected from 2009 to 2014, involve “a degree of statistical uncertainty.” What may be more relevant to most of us are the broad trends they identify.

The new research, for instance, echoes an earlier study that showed life satisfaction across Canada to be nearly an exact reversal of income levels. In a 2010 paper, Prof. Helliwell and Prof. Barrington-Leigh found that income levels go up as you travel west across the country, but life satisfaction goes down. Atlantic Canada was the happiest region in the country, despite unimpressive incomes. “The income difference simply wasn’t enough to offset the fact that people in the east had more time with family and friends, more trust in each other, and warmer connections with each other,” Prof. Helliwell said.

The researchers’ latest work shows that Canada’s unhappiest neighborhoods tend to be found in mid-sized or large cities in the centre or west of the country. The unhappiest community of all is a stretch of Hamilton, Ont., while Toronto has a couple of neighborhoods ranked in the bottom 10 and Winnipeg has three. Mississauga, Calgary, Richmond, B.C., and Surrey, B.C., also have markedly unhappy neighborhoods.

The top 20 per cent of happy neighborhoods don’t differ significantly from the bottom 20 per cent of neighborhoods in terms of household incomes or unemployment rates. What does vary is how strong an attachment people feel to their community. That goes hand in hand with affordable homes: Places where few people spend more than 30 per cent of their income on housing are generally happier than places where residents have to stretch to meet their mortgage payments.

Lots of elbow room and quick commutes also seem to be linked to happiness. “Average commuting times are 15 minutes in the rural areas, compared to 22 minutes in the city, while population density is almost 100 times higher in the cities than in the rural areas,” the researchers write.

Prof. Helliwell suggests that dense populations and long commuting times may not be evil in themselves, but rather in terms of how they affect the quality of personal relations. “One of the reasons cities are less happy than rural regions is that the level of social connection is less,” he says. “People tend to be less friendly because they’re more crowded, they’re rushed, they don’t know each other, they’re stuck in traffic jams.”

Fortunately, happiness may be more malleable than we realize. Quebec, for instance, has undergone what Prof. Helliwell calls a “quiet happiness revolution” that has seen its level of life satisfaction soar compared to the rest of the country over the past 25 years.

Money doesn’t explain the dramatic rise. In a 2013 paper, Prof. Barrington-Leigh examined several economic rationales for the spike in happiness and concluded none of them fit. One possibility, Prof. Helliwell suggests, is that Quebec’s growing life satisfaction reflects how a region once divided by language has evolved into a more confident society.

“I think it’s true, of francophones especially, that they feel more at home than they did 30 years ago,” he says. “It all speaks to how important it is to have a sense of belonging.”

Ian McGugan

Ian McGugan