Fighting for space

They’re gathering places on a hot summer day, the best spots to relax with a book or be alone with your thoughts, or to play a game of baseball with friends. But green spaces are increasingly difficult for cities to create more of, as residential and commercial developments grow at exponential rates and eat up remaining real estate.

How can cities develop more green space with the space they have? And what would a city that prioritizes public parks look like?

When Toronto’s Rail Deck Park is built, it will deck over the rail corridor from Bathurst Street to Blue Jays Way in the west end of downtown. The 20-acre urban park, which is expected to cost $1.665-billion, is a big opportunity for the city.

“It’s really the last opportunity to add a large park downtown,” said Claire Nelischer, a project manager at the Ryerson City Building Institute. “That’s something that’s a challenge for Toronto. We may be able to add small parks, but a healthy park network includes a range of park lands.”

Toronto isn’t alone in that challenge. Park space, which includes urban parks and natural conservation areas, are a vital part of healthy, vibrant cities, and their positive effects on mental health have been well documented.

But as Canadian cities grow, existing green spaces often shrink to accommodate new residential and commercial development. The opportunity to create new ones disappear as land becomes less available and more expensive.

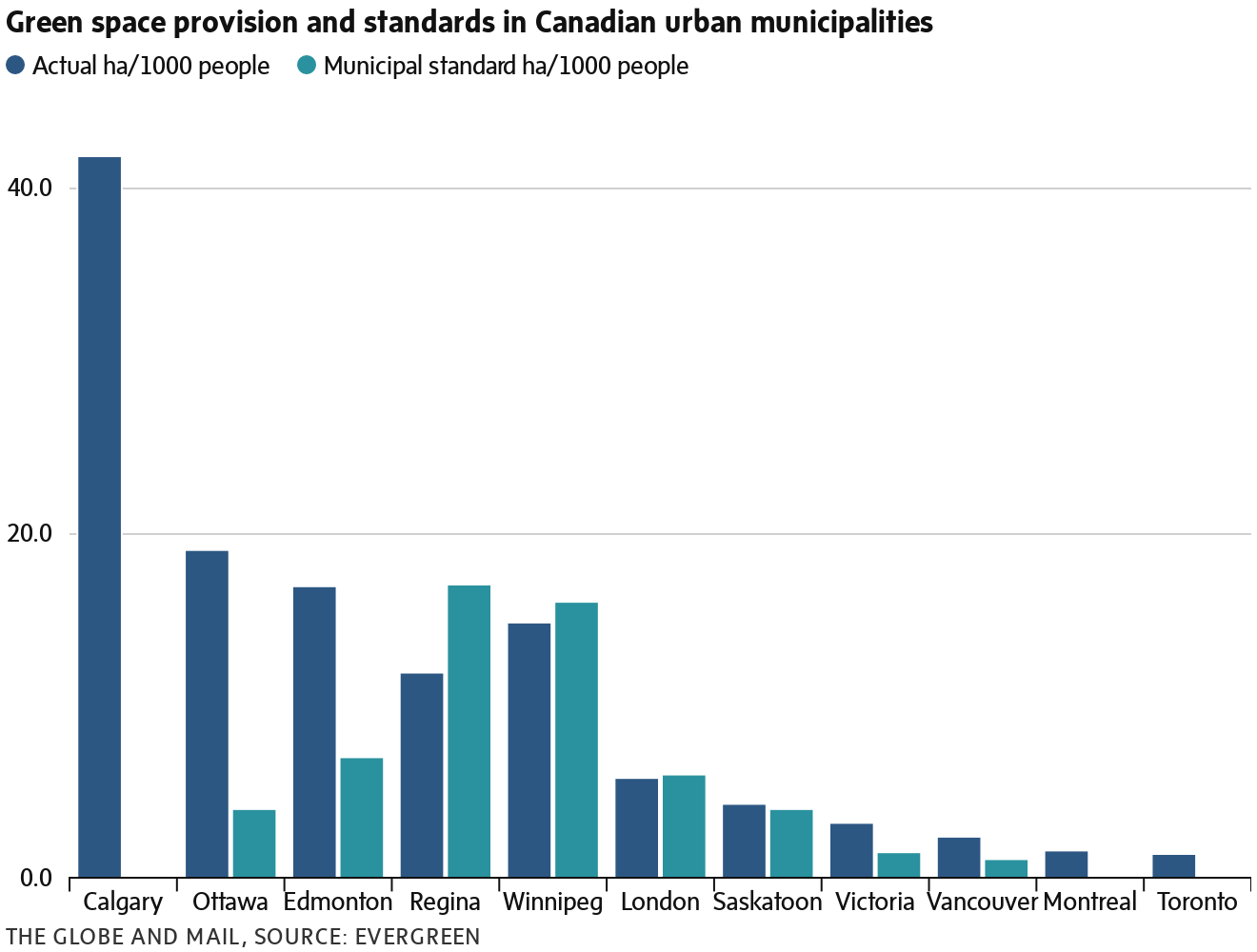

In a 2001 survey of Canadian cities, Environmental conservation advocacy group Evergreen noted that mid-sized cities like Calgary, Regina, Ottawa and Winnipeg were among the cities in the country with the highest ratios of green space to population — and in contrast, Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver had some of the lowest.

Today, with populations rising rapidly in all three cities — Toronto, for example, is expected to hit 3.4 million people by 2041 — those ratios are still lower, and it will be a challenge to even maintain their current states going forward, especially in the cities’ densely-packed downtown cores.

Development is most intensely concentrated there, and people live in vertical communities with no access to even a backyard. For that reason, Nelischer said, people living downtown “may be even more reliant on having open public space.”

Across the country, community groups are now stepping up to revitalize existing parks in their cities. Park People, a Canadian organization that began in Toronto, connects community park groups, city staff, businesses and other partners who want to work together to transform city parks. In May, they announced a collaboration with the Greenbelt Foundation on a $100,000 funding program for protecting urban river valley systems in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area.

Public green space has the power to connect communities and build more inclusive cities. It’s why TD partnered with Park People and other community organizations that seek to enhance park assets. Aside from the Park People grants, TD also started a national tree planting program in 2010. Every fall, volunteers gather at over 150 events across North America, and cumulatively have led to over 300,000 trees planted – the equivalent of 1,235 cars being driven in one year.

Recognizing the importance of investing in building more inclusive and sustainable communities, TD launched The Ready Commitment in 2018. As part of that, TD has targeted $1-billion towards community giving by 2030 in four different areas, one of which, called Vibrant Planet, will focus on enhancing green spaces and supporting the transition to a low carbon economy.

"We want to get people thinking differently about our natural assets and the value they provide," says Nicole Vadori, head of environment for TD. "The value of one tree goes far beyond its initial price tag.”

At the city level, Nelischer said she has seen some encouraging examples in Toronto of “making use of older infrastructure to meet new needs,” like the creation of the Bentway under the Gardiner Expressway, and the expansion of the Meadoway, a formerly barren power corridor in Scarborough that has become a 16-kilometre urban greenspace.

In some cases, private sector actors have undertaken major park revitalizations, or created new ones altogether. Grange Park, a 1.8-hectare park in Toronto with a community pool that is managed by the Art Gallery of Ontario, was recently reopened last year after a $12.5-million facelift.

TD has also funded major park projects across the country — last year, for Canada’s 150th birthday the bank revitalized 150 parks across the country, including seven major flagship projects.

“We’re working on activating green spaces,” said Nicole Vadori, TD’s head of environment. “They’re vibrant and beautiful places that bring people together. We’re trying to get people more connected to the environment.”

Photography: Globe staff, TD, City of Toronto, Grange Park Advisory Committee, iStock, 500px

This content was produced by The Globe and Mail's Globe Content Studio, in consultation with an advertiser. The Globe's editorial department was not involved in its creation.