iStockPhoto / Getty Images

Craft beer is becoming increasingly popular, but the industry itself doesn’t reflect the diversity of its clientele.

According to the Brewer’s Association, an American organization with the goal of promoting and protecting craft brewers and their beers, in 2019 the demographics of the industry ranged from “76.2 per cent white for production staff (non-managers) to 89 per cent (brewers).” It’s difficult to find statistics for the Canadian industry, but it’s clear that trend holds here, too. Things are slowly changing. In July, the Canadian Craft Brewers Association launched an Anti-Discrimination Committee in “an effort to combat racism and discrimination in the craft brewing industry in Canada.” But there’s still work to be done.

“Historically, the first beers were made in Mesopotamia, and they were made by women. Brown women,” says Ren Navarro, founder of Beer. Diversity. “If it weren’t for women, we wouldn’t have beer the way we do now.” Next, she steers our conversation to the Middle Ages, when “brewsters,” or women brewers, dominated the beer industry—and were often branded as witches. (The reason we associate tall, pointy hats and broomsticks with witches is actually because that’s how brewsters used to market themselves.)

Navarro’s message is clear: beer has always skewed toward a particular demographic, and it’s time for some change.

To do her part to bring change to the brewing industry, Navarro founded a consulting company aimed at increasing diversity in beer in 2018. And she wasn’t shy about the goal of her business—it’s named Beer. Diversity., after all. Fast-forward two years and she’s a well-known, well-respected name in the industry.

Her message is consistent: There’s room at the table for everyone. Navarro’s aim is to educate and inspire brewers and consumers to scoot over and be inclusive in their branding, distribution, staff and community management. “We need to stop with this secret handshake and secret knock. Breweries say, ‘our door is open’ but it’s not always,” she says.

How can they do better? Invite people from different backgrounds to show their techniques, but always acknowledge and never appropriate. “Incorporating other cultures' fruits or spices into something… that’s how you break down the secret handshake or knock,” she says.

And if you need some help figuring out how to stock some diversity into your fridge, take Navarro’s advice: “Don’t ask your Black friends—Google works faster.”

Eden Hagos' brand is a great place to start. As a kid in the 90s, Hagos used to visit her family’s Ethiopian restaurant—one of the first in Windsor, Ont.—and enjoy meals prepared by her aunt and uncle. She observed the joy of preparing and sharing a special dish (like injera, a slightly spongy Ethiopian flatbread) and internalized the lessons that food and drink help forge bonds and feeding people is a way to show love.

Years later, Hagos is the founder of blackfoodie.co, a platform built to celebrate and promote Black food. She’s admittedly not a huge beer drinker, but she knows the history of the brewing process and how good drink is arm-linked with good food.

“Beer is a part of the culture,” Hagos says. “Ethiopian beers are made at home; it’s the original craft beer. Red Stripe is part of Caribbean culture. Oftentimes restaurants are a piece of home for someone that maybe hasn’t gotten to visit their home in years.”

And they’re also an opportunity to branch out and discover new things. “I eat Caribbean food at least two to three times a week. I don’t have roots there, but I love it so much,” she says.

Luckily, trying a new-to-you dish or bev doesn’t take a lot of legwork in Ontario, with its diverse culinary scene. In fact, sometimes the hardest part is just deciding to try something new. “There can be an uneasiness when something is unfamiliar, especially with African food,” Hagos acknowledges. She encourages everyone to have an open mind and not to be afraid to ask questions or do some research—and that maybe it’s worth starting by trying a new beer.

Like the craft brews from Mascot Brewery, for instance. After all, with his East Coast hospitality background, beer and good times are synonymous for Aaron Prothro, founder of Mascot. “I’ve always associated bringing people together and the sense of happiness and joy that comes from trying new beers,” he says.

Ask him about craft beer and you’ll hear the passion in his voice as he talks about starting his business and how much he loves supporting local. “What you drink in this day and age represents you as a person,” he says.

Prothro likens beer with good times (rightfully so), and that was part of the approach he wanted to recreate at Mascot. With more than a dozen varieties on tap at their two locations, you can also find their pilsner on LCBO and The Beer Store shelves, which is not an easy market to break into.

But when asked what it was like forging a path in a small and predominantly white industry, Prothro is modest. “I’m a pretty bullheaded person, so I never paid attention as much to those barriers. I never looked at things from the perspective of ‘oh, this is hard because I’m a mixed-race guy trying to do beer,’” he says. Still, “there’s definitely some adversity there. The craft beer industry is very welcoming, but at the same time, as you get more into it you start to notice different attitudes.”

He’s a private person and isn’t comfortable with too much attention or praise for his trailblazing. But he does see the value in talking about it, at least a little. He wants “people [to] see it’s something you can do,” Prothro says.

“If someone else looks like me and I can inspire them to open a brewery, it’s worth it for me to put myself out there.”

Beer + Cider Tour

These breweries (and one cidery!) amplify BIPOC voices, prioritize community and support anti-racist causes

Lost Craft

Toronto-based Lost Craft bills itself as Ontario’s first minority-owned brewing company, and its approach is to “think global, act local.” That means its brews are inspired by interesting beer styles from around the world—but diversity and community are core values.

Manitoulin Brewing Co

Situated on Lake Huron island, Indigenous-owned Manitoulin Brewing Company taps into the region’s iconic landmarks with brews named after Cup and Saucer Trail and Little Current Swing Bridge, which connects the island to the mainland.

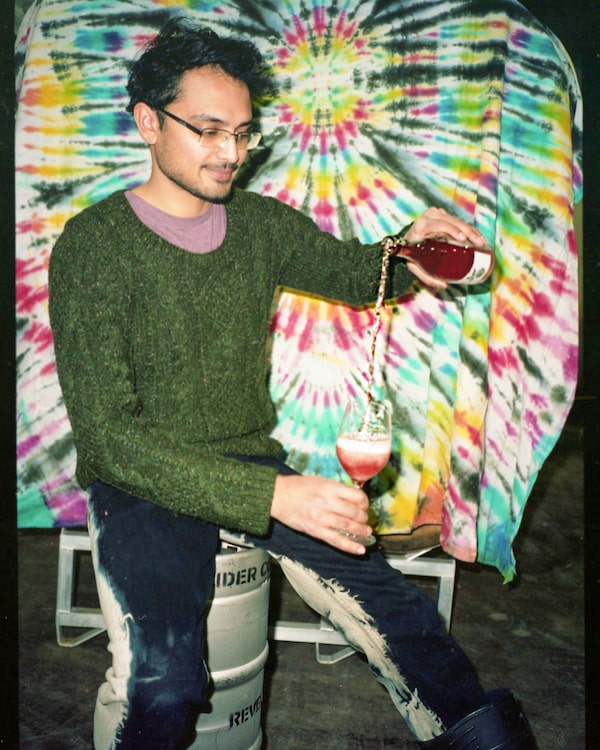

Revel Cidery founder Tariq Ahmed, who got his start interning with ManoRun Organic Farm in Copetown, Ont.Handout

Revel Cidery

POC-owned Revel started from a passion for food and drink fermentation. Founder Tariq Ahmed started experimenting with native yeast fermentations to make aged ciders and wines while completing an internship at ManoRun Organic Farm in Copetown, Ont. And he never really stopped. This year’s new releases include Nimbus, a cider aged on golden plums and Gewurtzraminer lees (leftover yeast particles) and Lucid, which is aged in tequila barrels alongside Muscat skins. Ahmed is donating $500 from the sales of all of his 2020 releases to organizations that are fighting systemic racism.

The Second Wedge Brewing Co.

On the scene since 2015, The Second Wedge Brewing Co. is showing up in small-town Uxbridge. Among their lineup of brews is a slow sip called Black is Beautiful with all profits going to Ontario’s Black Legal Action Centre, a non-profit offering free legal services to low-income Black residents.

Brunswick Bierworks

You don’t have to dig far to see how Brunswick Bierworks is working to fight systemic racism. They acknowledge their privilege and responsibility on their homepage, and pledge to continually donate and support BIPOC organizations. So far, they’ve supported Black Lives Matter and the Black Business & Professional Association.

Explore The Great Taste of Ontario at ontarioculinary.com/great-taste

Advertising feature produced by Globe Content Studio. The Globe’s editorial department was not involved.