Facts & Arguments is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

I am a very emotional person. Maybe it's part of my personality or maybe it's because I fall under the category of moody 17-year-old girl.

I'm emotional when I get a bad mark. I'm emotional when I get in a fight with my friends. I'm emotional when I hear about a tragedy in the world.

The last one is part of human nature. We naturally feel sad when we hear the news that someone has passed away unexpectedly or that a catastrophe is happening on the other side of the world. It's sincere, but it's brief. I am occasionally guilty of this.

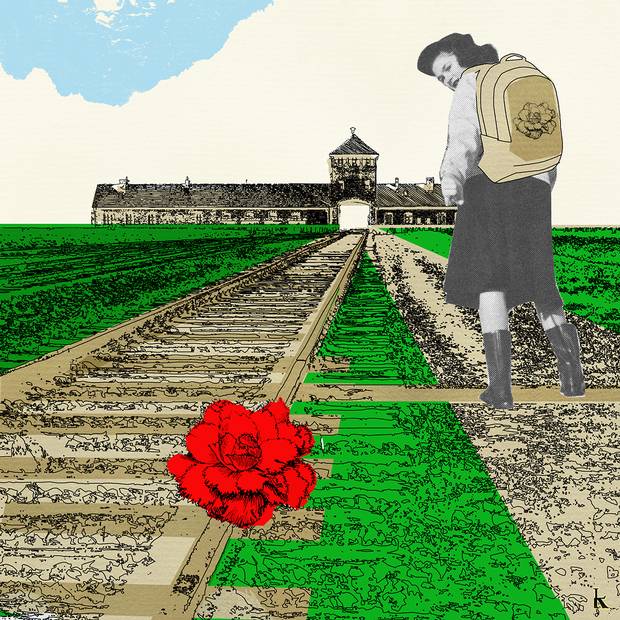

My entire mindset on what constitutes a tragedy changed in May, however, when I was part of the 2016 March of the Living. This is a two-week Holocaust-education trip for which Grade 11 students travel to Poland for one week and to Israel for the next.

The two weeks exposed me to such atrocities that it seemed they must have been separate from the world we live in, that they could not have happened in our time.

I placed a wooden sign on the train tracks to Birkenau to commemorate the 9,000 people killed daily in the death camp.

I stared at the masses of hair that had been shaved to humiliate prisoners arriving in Auschwitz.

I stood in gas chambers in Majdanek, where tens of thousands of people were poisoned with Zyklon B gas.

I walked through what is left of Treblinka.

I mourned for the 400 children who were brought to a forest and shot in pits in Tikochin.

I listened to survivors recount the times they were forced to shovel up masses of corpses, some of whom were their friends and family.

I found myself in the shadows of a catastrophe that has no direct connection to my current life. It's as if you were given a tour of the Bataclan theatre, where one of the Paris attacks took place. You stand in the footsteps of people who have lost the meaning of their lives – it is an indescribable feeling.

On each bus of the trip, a Holocaust survivor accompanied the group and we were able to experience a small part of their lives. We listened to their testimonies at the places where they occurred – such as a barrack in Birkenau. Susan, the survivor on my bus, was in hiding as a child. Bill was a slave labourer for the BMW car company. Nate was a prisoner at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

For the first time in my life, I was exposed to a new magnitude of pain: a pain so deep it clouds your mind and governs every inch of your body; an emotional pain so brutal it becomes physical. It is the pain that comes from seeing your mother shot before you; it is the agony of watching helplessly as your brother is whisked away to a gas chamber. It is an all-consuming, life-altering pain that one can never forget.

I could not fathom how the survivors had continued on with their lives – and yet they had. Their ability to overcome such horrors showed me that, in the end, maybe strength can conquer pain.

I learned much more than I could have ever imagined during this trip. I developed an appreciation of what it means to have family, to be healthy, to be alive.

We hear about tragedies on the news and we feel sympathy for a few minutes, then we continue to pour our coffee and text our friends because the pain isn't real to us. We hear the stories of victims of terrorist attacks and car accidents, of people struck by illness and misfortune, but we are not able to truly understand the extent of their suffering.

I saw with my own eyes physical evidence of atrocities and heard personal recollections of them. Because of this experience, I was able to uncover the true depths of pain and how to better empathize with victims.

I learned something that had such an effect on me, it changed the way I look at the world.

Imagine a line. This is the spectrum of humanity. At one extreme, we have good and far removed, at the other, we have evil. This spectrum is what we visualize as humans' full potential. The Holocaust extends beyond the boundaries of evil; it is immeasurable. The pain of the victims is immeasurable.

But there is much more to the spectrum. If so much evil can exist, to the point that it has no limit, then the same applies to the other end. We hold the ability to do so much good for humanity, more than imaginable and more than can be measured. We have infinite power to do good in our own hands.

So after your few seconds of reflection to mourn a tragedy that isn't directly related to you, think of how lucky you are to be alive and remember that your potential to bring goodness to the world has no limit.

Rachel Rothstein lives in Toronto.