Facts & Arguments is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

One year ago, my sister and I discovered that our adult brother had a horrible illness. No, not cancer, or some other physical disease, but a disease of the mind – delusional (persecutory) disorder.

How did we find out? He didn’t phone to tell us – one of the hallmarks of this disorder is denial. The afflicted person rarely believes there is anything wrong with them.

Its presence in our brother’s life crept up on us. Maybe it had been creeping for years and we’d missed the signs. Now that he and we are in the thick of it, we will never truly know.

Most people are hardwired to try to fix problems and help others, so last year at this time we set out to “fix” our brother’s problem. Devoted and optimistic in those early months, we researched all we could, spoke to friends, doctors, lawyers, police and others, and made four visits to Toronto from the other side of the country trying to figure out how to make things better for our brother.

We were thankful we were living in an era when mental-health issues have come out of the closet. After all, we live in the times of Bell’s Let’s Talk campaign and the like. Our brother lives in Toronto. We assumed help would be readily available. We were naive.

After endless frustrating efforts, a modicum of relief set in when our brother ended up in hospital for close to three weeks last summer. We were hopeful that the medications and other support (which turned out to be much less than we expected) would solve his problem.

He seemed to be improving, but it turned out that he completely believed that the doctors were also against him, just like his neighbours and workmates. He took the medications just to make the staff happy so he could be released.

He was able to connect those dots, but in other ways had lost all sense of cause and effect. Once released he stopped taking his medications and still did not believe he had a problem. In the psychiatric world, this is referred to as “lack of insight.”

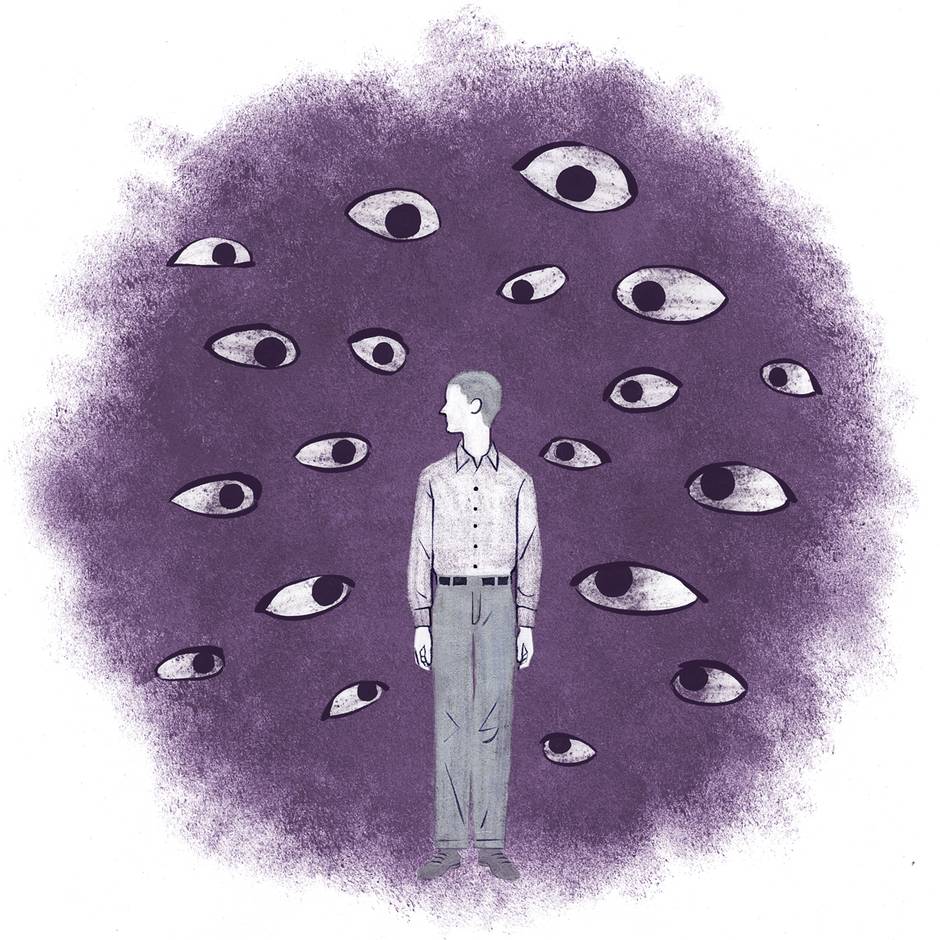

For many reasons, loneliness has been a fact of our brother’s life. Delusional disorder has made it worse. The delusions that torture his mind are part of his conversation for anyone who will listen. Not many will any more, because they are frightened of the things he says. He cannot understand why people do not believe he is being followed and watched on cameras at home, at work and everywhere in between. With great frustration and sadness, he tells us that people completely ignore him at home and work. That, I believe to be true. Who wouldn’t try to avoid a person who speaks irrational thoughts and turns on you if you don’t buy into his beliefs?

We learned a little too late that we should never challenge his delusions, that in order to help him continue to trust us and to preserve some sort of relationship we should listen neutrally – neither denying nor embellishing the delusions. This isn’t easy to do when you see someone you love being tortured day and night by bizarre beliefs.

We are learning that there is mental illness and then there is mental illness. For close to a year, we have been trying unsuccessfully to find a psychiatrist, a doctor or anyone in the helping professions who has an interest or specialty in working with people with delusional disorder. Every single door has slammed shut. It appears that no one wants to work with this type of disorder.

And even if we did find someone, how would we get our brother to see the person? He is highly suspicious of doctors.

As the failed attempts to help our brother find relief from his delusions (and by extension, some joy in life and peace of mind) mount up, we ourselves are starting to suffer from intense worry, frustration and sleepless nights, and have sought out our own help to cope better with the situation.

Recently, my sister reminded me that when a close friend of ours was dying of cancer a few years ago, we stopped trying to find solutions for her illness and accepted her fate. Why, my sister asked, are we not more accepting of our brother’s illness?

One year after his hospitalization, he has not improved. In fact he has regressed.

Sadly, there was no follow-up from the overburdened medical staff. People with mind disorders often fall through the cracks, especially if they have a job and can make it to work every day as our brother has been able to do.

But the circles are darkening under his eyes as his thoughts taint his every waking and semi-sleeping moment. He is so invested in his false beliefs that simple suggestions from caring family members are rebuffed with anger, profanity and accusations that we are like everyone else – we do not believe him.

I have today hit the wall of despair. No amount of money, worry or sleepless nights will solve his problem. He might become worse. He might never get better. This disease, like a terminal illness, may have no cure.

Now, I am sadly repeating a mantra over and over: “Please give me the grace to accept that which I cannot change.”

Samona Easton is a pseudonym, chosen to protect the identity of the author’s brother.