Facts & Arguments is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

Academics often have to fly to conferences. They are a great way to get one’s work out to the academic community, to network and to reconnect with old friends. Naturally, we look forward to them.

Conferences are also costly: conference fees, association membership fees, flights, hotels and other logistical costs. There are also non-material costs associated with lost time, energy and, sometimes, health. But there is one type of cost that only some of us have to bear: the cost of colour.

As a scholar of transnationalism and immigration, I am all too aware of the cost of racial profiling in international travel in the post-9/11 world. And I’ve been subjected to some covert racial profiling – unlike my partner, also an academic, who often gets blatantly profiled as a Muslim man and bears the brunt of harassment whenever he’s travelling. Following a few egregious experiences, he did not leave the United States for eight years for fear of being harassed and detained. His conscious refusal to be humiliated every time he travelled cost him the opportunity to present at and participate in many prestigious international conferences.

While I have been bothered by the fear of profiling for years, a recent string of personal events compelled me to write about the hidden and cumulative cost of travel for people of colour.

Last year, I moved to Calgary with my partner to take up a post as a sociology professor. After participating recently in an invigorating conference on “Unequal Families and Relationship” in Edinburgh, I was flying back to Calgary, travelling via Glasgow, where I had spent a day before boarding my flight home.

It was four days after the Orlando shootings and one day after the murder of British MP Jo Cox. While in Scotland I had overheard much Islamophobic outrage over the Orlando shootings, but less outrage about Cox’s killing (a white man has been charged). Glasgow seemed particularly unfriendly to me. People were rude and unresponsive. I had loved Edinburgh (I was always with and around colleagues there), but I was glad to get out of Glasgow.

I made it to the airport bright and early. I had checked in online, but hadn’t got a boarding pass due to a glitch, so I stood in line at the desk of my Western Canadian airline carrier. I was the only person of colour in the queue. Out of nowhere, a white airline agent approached me, asked for my passport and pulled me out of the line. She asked where I was going, why I didn’t have a boarding pass and what proof I had that I was on that flight. I realized I was being profiled.

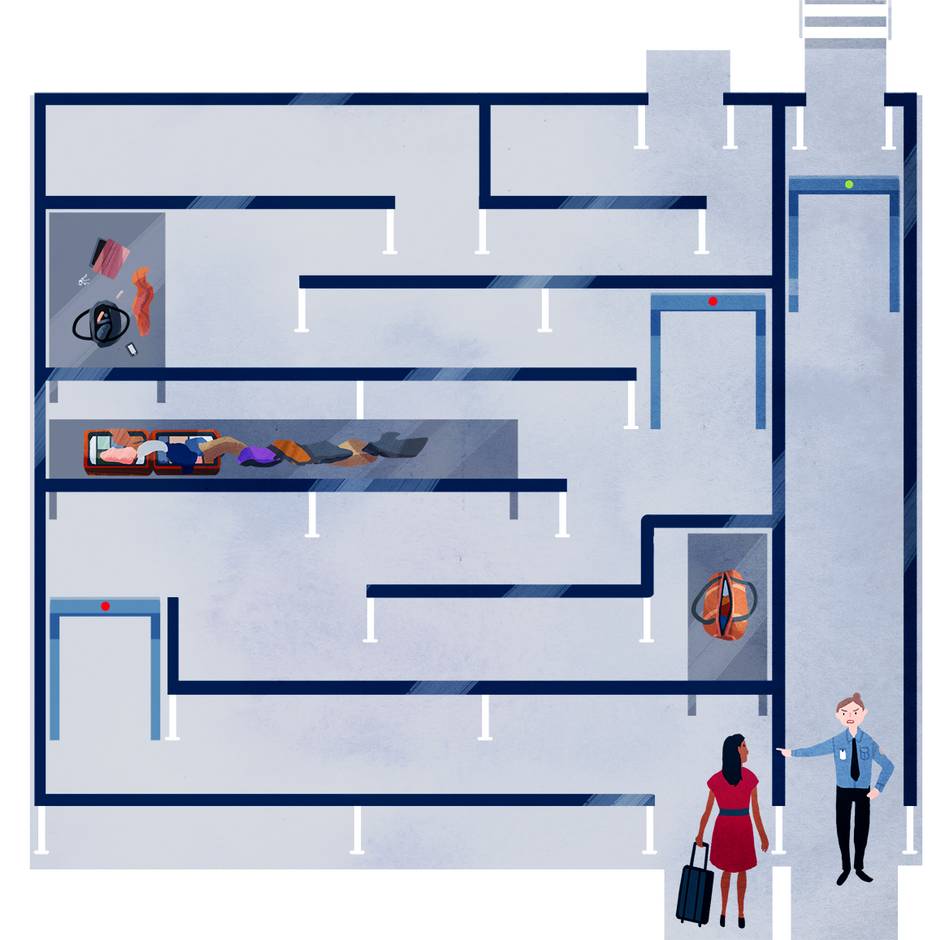

Perhaps it’s a reaction to Orlando, I thought. Or perhaps the woman is living her racist fantasy. Regardless, I was powerless. Then the ethnographer in me kicked in. I started taking mental field notes. She questioned me for 20 minutes, then walked away with my passport for 15. Meanwhile, the line grew. When she returned, I asked her why I was singled out and she said, “Do you want me to give you a lesson?” I stared back blankly. She continued: “… because the other people in the line have British, Canadian or American passports. And people with your kinds of passport do all kinds of things that are not legal. The Canadian High Commission has instructed us to be extra careful with people with your kinds of passport.” I told her she was racially profiling me and asked her name. She glared and put a purple sticker on my passport that said “security.” At security, my bags were searched.

When I finally made it to the gate, the plane had started boarding. The same airline agent was at the gate. Though I was troubled to see her, I hurried on to the jetway – and right before I stepped into the plane, I twisted my ankle. It swelled up, but I could still walk with a limp. I’m sure it would have been fine, but the flight crew decided to deplane me instead and get a medic to check it out. They asked me to get a doctor’s letter stating I was fit to fly before I could get on their plane (yes, all because I’d twisted an ankle). At that point, ground staff (two friendly white women) took over and wheeled me out of the airport.

Feeling humiliated and worried about the medical bills I was about to incur, I hobbled to a taxi and went to a hospital in a city where I knew not a soul. A doctor checked me, did X-rays and figured it was a mild sprain. She gave me a clear-to-fly letter and I didn’t pay a dime – the National Health Service covered it. But I did pay to stay overnight in an expensive hotel by the airport. Feeling alone and vulnerable, I posted about the incident on Facebook. My friends immediately responded with support and love, but what was telling was that, while a few of my white friends were surprised, most of my brown and black friends shared stories that were uncomfortably similar to mine. I did win the crown with my ankle sprain, but the rest of it was far too common.

Back in Calgary, I’m recovering from my sprain and also the heavy, and now not-so-hidden, cost of my trip. I lodged an official complaint with the airline and they responded quickly with a gesture of goodwill – a voucher. But I still feel enraged and traumatized by whathappened.

Pallavi Banerjee lives in Calgary.