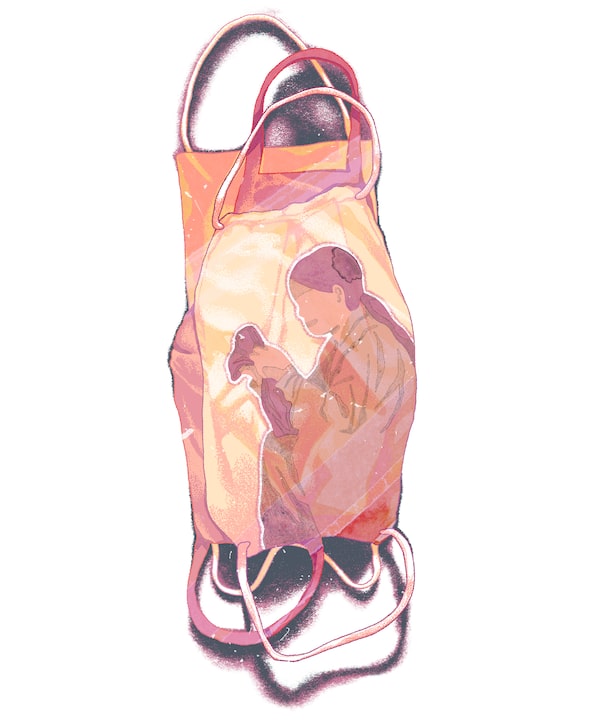

Illustration by Rachel Wada

After this pandemic is over, I’m going to keep on stitching. I did a lot of sewing as a teenager. It felt like an invisible cocoon took shape around me as I guided the fabric with my fingertips to the sewing machine’s gentle judder. Here I found refuge from the occasional dark days of adolescence. My aunt started me off with a length of white cotton dotted with tiny red embroidered strawberries. I made a blouse with puffed sleeves.

In later years, I stopped sewing after making a few quilts for our kids when they were young. Their activities, my job and writing filled the days. I will quilt again when I’m old, I thought.

There is no shortage of cloth. When we moved to our current home 20 years ago, my fabric stash was stuffed into garbage bags and filled the back of our half-ton truck. My husband hiked the bags up into the garage’s attic and strapped them onto the rafters under the roof.

I rationalized my urge to collect and hoard fabric by saying it fulfilled an underused hunter-gatherer instinct. It’s also about stories: All those designs trigger associations and memories. Fabric language is as expressive as body language. Sewing masks during the pandemic has affirmed this.

Fearful for family members who live in large cities, it was a relief to mobilize my arsenal of sewing implements.

First, I found a mask pattern online. I printed and pasted it with an ancient glue stick onto cardboard and cut the template out. There was great comfort in using these artisanal tools again.

Then I went into the attic where my treasure waited patiently, aging like bottles of fine wine.

The first bag I dumped onto the dining-room table was a batch of discontinued fabric samples from my friend’s futon store. (We’re both flute players and met at university in a youth orchestra.)

The cottons are thick and tightly woven, as recommended by medical officers of health. I choose obedient plaids for guys and demur florals for gals. I trace around the cereal box template with a decades-old pencil crayon and cut out the mask’s two sides.

Now the sewing machine is deployed. My foot on the treadle sets the gentle, light hammering action of the needle into motion.

I think about my futon-store-friend who is a sensational flute player. She passed on a simple exercise that helped my playing, too. Puffing out my cheeks would loosen and eliminate the tension in my embouchure muscles, resulting in a free, natural sound. During my 30-year teaching career, all my flute students benefited from her puffy cheeks exercise. We are like a dispersed flute dynasty with our warm, silvery tones.

Reminiscing about my flute-friend as I give the mask a final pressing helps me gain some equilibrium against the current horror.

I empty another bag. One remnant, a riot of neon colours, seems to leap onto the table. Bright blue and sunny yellow cartoon-like dinosaurs with happy smiles and spikey backs are superimposed on a wobbly purple grid filled with a jumble of red circles and green triangles.

This piece is from my designer-friend, who established a children’s clothing line in the 1980s. My young sons loved their dinosaur pants. I know I can edit out the juvenile dinosaurs for a mask, but is the chaotic arrangement of colours and shapes too wild for my adult sons?

I go all the way back to high school with this friend. We’d sit on her bedroom floor discussing fabric options while leafing through Singer Sewing pattern books. Our imagined fashions wound us up into an exhilarating frenzy. I feel that creative excitement stirring again as I shift the cardboard template around to avoid the dinosaurs. The finished mask reminds me of Kandinsky’s colour studies. I text a photo to my son. He assures me that it’s fashionable.

Making and then mailing masks to him is more constructive than ruminating about his temporary loss of taste and smell.

My 1960s and 70s collection got a significant boost when my Grade 13 English literature teacher passed away. I’m indebted to Miss P for teaching us how to organize information to write an essay. I preferred to write willy-nilly because it felt more poetic, but she convinced me that poetic thoughts fail without clarity. Miss P was a single woman with no family nearby. Her executors posted an ad in the newspaper inviting her friends to take a gift from her apartment. I chose a teacup and a John Steinbach paperback. As I was leaving, I passed the open closet, which revealed a colourful array of clothes. I found myself offering to take them. I told the overwhelmed executors that I’d keep the cottons for quilting and donate the rest to charity.

Twenty-five years later, I tip her clothes onto the dining room table. Gruff Miss P, whose cheeks shook scarily when she was angry, wore a go-go dress? Clusters of hot pink daisies and purple tulips bloom atop wavy lime green, mustard yellow and bright turquoise lines. I remember her only in loose polyester pantsuits. Still, as I cut the seams of the go-go dress open, I can imagine her wearing it when she was young. I loved how she used to say “a catharsis is a cleansing of emotion,” after we’d all been quieted by a poignant reading.

It is cathartic, in this sorrowful time, to sew against COVID-19. While the sewing machine and I drum along, I’m grateful for the emotional relief generated by the spirit of those long-ago relationships.

Our ability to share and collaborate has a powerful energy. It’s a marvel to see the innovative scientists, the steadfast front-line workers and many of us ordinary people exerting our best selves to persist through the dark days of this story.

Dorothea Belanger lives in Kenora, Ont.

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.