History is peppered with quotes that are laughable now – 1947’s “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers,” by IBM chairman Thomas Watson, or 1911’s “Airplanes are interesting toys but of no military value,” by Marechal Ferdinand Foch of the French military – because the speaker was too mired in the day to day to extrapolate or, more importantly, to dream just a little.

Those two quotes resonate today because 3-D printing – the technology that turns an on-screen schematic into a hard, three-dimensional object – may still seem like a toy that belongs with geek computer clubs or in the hands of eccentric Doc Brown-types who also tinker with old DeLoreans. And, even to those who recognize its potential, it’s still far-fetched to think these machines will eventually be as common as regular paper printers in our homes.

That’s why 3DXL, an exhibition by the Design Exchange (DX) at a satellite location at King Street West and Blue Jays Way, is so important. Running May 14 until August 16, 3DXL takes the technology (invented in the 1980s) out of dark university labs and nerd bedrooms and puts it at street level, right in the heart of the city. And instead of presenting the usual small-scale objects, such as architectural models, jewellery or eyeglasses, it blasts our senses with extra-large things: tall sculpture, wide enclosures, real furniture and, yes, even the building blocks of a full-sized home.

“The real challenge with the technology now,” curator Sara Nickleson says, “is in structural integrity and volume in creating large pieces.”

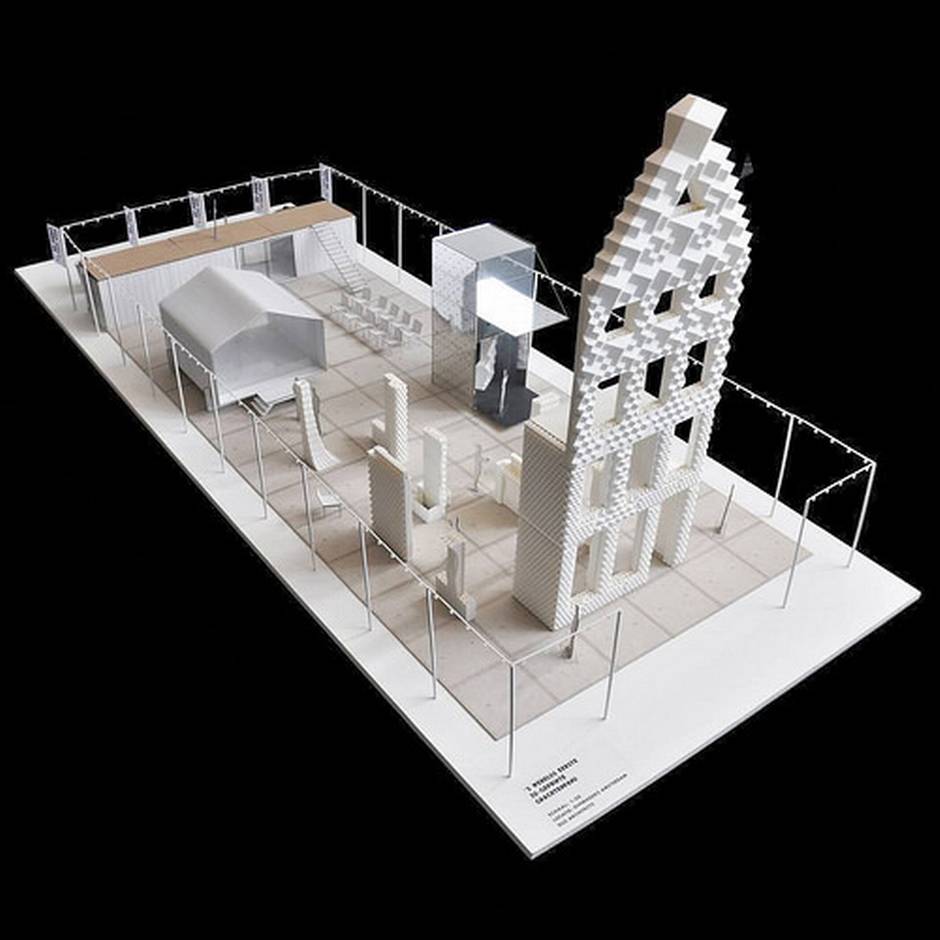

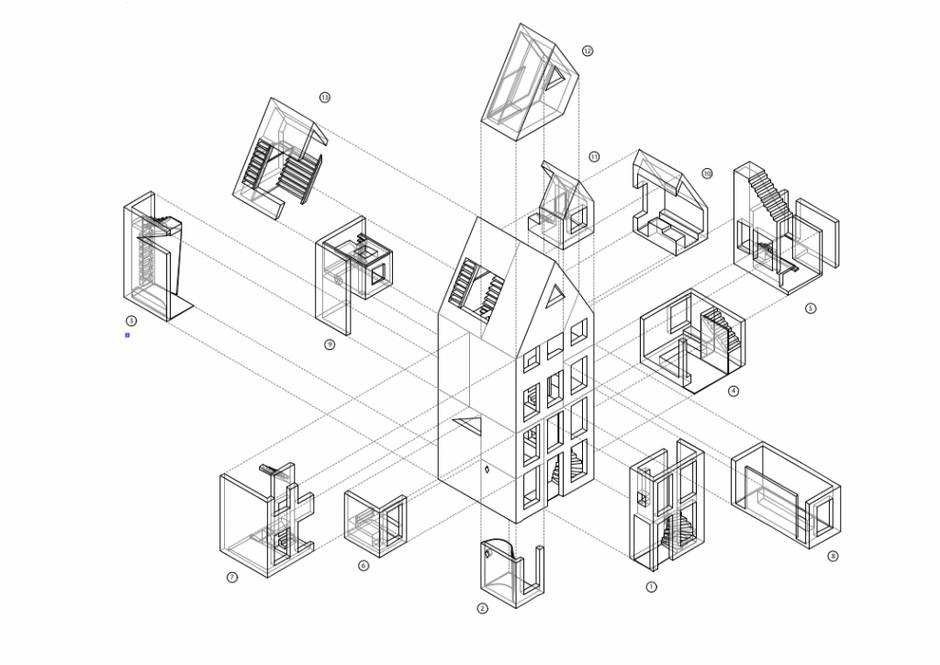

And the best example of that, she continues, is by DUS Architects, who are printing an entire house, 3D Print Canal House, beside a canal across from downtown Amsterdam. A piece of that building will be on display, as well as a large-screen video of DUS’s Kamermaker, a 3-D printer the size of two elevator cars stacked on top of each other. This giant printer, says Tosja Backer, manager of the project at DUS, means that in addition to 3-D printing a small test piece, the company can just “scale it up” to life-size. “And that’s just a really, totally new way of rapid prototyping,” Ms. Backer says. “You can immediately test, on the building site, what your building does.”

Should gallery-goers look closely at DUS’s printed block, they’ll notice openings and channels; these must be filled with concrete before use, since a “completely 3-D printed home,” Ms. Nickleson admits, is still in the future. However, she stresses we’ll get there: “They can 3-D print with metal now, so even if it means 3-D printing the structural portion of it, and then printing the façade or the interior in a different material, I think it could happen,” she says. “I’ve heard people talk about, you know, you see cranes set up to build condos now – one day those will be 3-D printers.”

The day might come where printing sculpture to decorate one’s home will also be the norm. While Benjamin Dillenburger and Michael Hansmeyer’s tall and imposing Arabesque Wall looks a little like a Victorian-era acid trip rendered in sandstone, it displays the potential of printing large-scale sculptural pieces. Look at the incredible detail these Swiss architects have achieved, and it also points to what’s possible in the heritage restoration field: Imagine an expert in England e-mailing the design for a rare piece of crown moulding to a restorer in Toronto, who then prints the pieces he or she needs.

Also on display will be the work of some of Mr. Dillenburger’s students (he teaches at the University of Toronto).

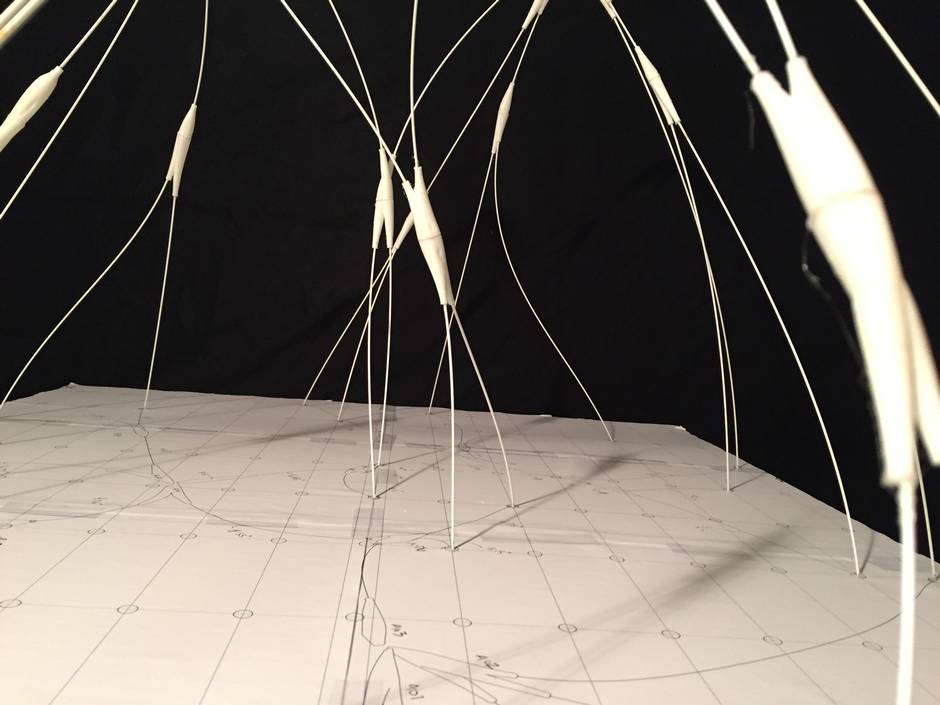

A semi-enclosed shelter, Mangrove Structure, by Denegri Bessai Studio, shows how 3-D printing can be used to create connector pieces that work with existing materials. The structure will consist of flexible tubes, which were not created with a 3-D printer, connected to one another by 3-D printed “nodes” to create a domed, tent-like space. “You’ll be able to walk through it,” Tom Bessai says, “and when you touch it, the whole thing is interconnected, so it’ll vibrate a bit, and we have sensors in these upper nodes … and the illumination will vary.”

Interestingly, each node is a unique shape based on both load requirements and material efficiency: “It costs the same,” Ms. Nickleson says, “to print customized pieces – all of them different – rather than actually having to have something mass produced, which is a real benefit of the technology.”

To satisfy the “hackers” out there, 3DXL is presenting architects from London’s Bartlett School of Architecture who have modified a robotic arm – the kind that does repetitive work in automobile plants – to become a 3-D printer. It will print one full-sized chair a day.

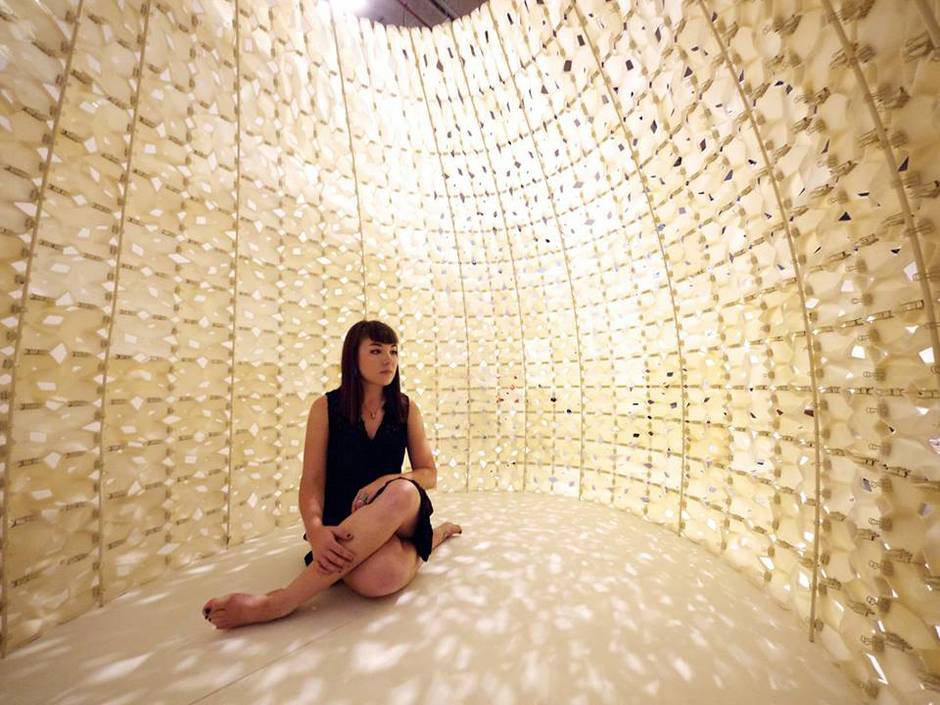

Also on-site: an igloo-shaped pavilion printed with sea salt (!) by California group Emerging Objects and an interactive area headed up by Ryerson instructor/cabinetmaker Adrian Kenny and his students, who will be on hand to answer questions from curious gallery-goers.

And there’s no doubt in my mind that there’ll be hundreds of questions every day, as this is an incredible show that stimulates, challenges and excites.

It even tempts yours truly to write something along the lines of “In 10 years, we won’t know how we lived without 3-D printers,” but, in case that prediction is wrong, pretend I said nothing.

***

3DXL runs May 14 to August 16, 2015, in a converted condo showroom at 363 King St. West. General admission is $11. See www.dx.org for more info.