Red boulders, large and small, lay scattered across the barren landscape. A dry riverbed wends its way toward the craggy mountain range. Tucked into its bank several metres away, an oddly-shaped shelter confirms our party was not the first to visit here; closer at hand, spiky plants threaten to nip at unprotected skin: “Now do watch it,” cautions our guide. “These don’t bend, they’re hard, and they will poke you.”

If it weren’t for the blue sky above with the dark clouds threatening rain on the horizon, this could be Mars.

Alien, yes, but this is merely the Sonoran Desert behind Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West, an architecture school that has perched on the McDowell Mountain foothills above Scottsdale, Ariz., since the 1930s. And, for just as long, apprentices (a.k.a. students) here have been designing, building and inhabiting shelters as part of the school’s “Learn by Doing” philosophy.

Current student Christopher Lock, 48, an affable one-time English teacher from snowy Michigan, takes us to see “Tree House Shelter” first. William Schoettker’s 1990 design is the perfect introduction, since the little building is so Wrightian it could pass for 1950: a generous roof overhang shades almost-floor-to-ceiling windows sporting multi-angled muntin bars; inside, an oxblood-tinted concrete floor and raised triangular fireplace create instant intimacy.

“I think this is one of the better fireplaces,” says Mr. Lock, who then points to the ceiling and tells the story of how, before he could move in a few years ago, student Pablo Moncayo had to restore the roof because of a giant termite mound on top.

That’s the thing: since Taliesin retains ownership of the little dwellings, it allows for new students to renovate/restore an older shelter rather than create one from scratch. And since there are only 50 approved sites on the school’s 251 hectares – add more and “it would feel like a little city, and we want to be in the desert,” Mr. Lock explains – that’s sometimes the quickest route to getting one’s own place while enrolled. And although it’s not mandated that students live electricity- and plumbing-free among the scorpions, snakes, pig-like javelinas and coyotes, it is strongly encouraged (hey, you want to stay soft, go to another architecture school!).

Consider, however, that one-third of the sites contain only foundations – probably poured more than a half-century ago when the popular choice was the shepherd’s tent – and that Taliesin’s small student body is made up of risk takers, oddballs and “alternative thinkers,” and it makes sense that a number of applications for ground-up construction are filed each year.

For instance, our next stop features Trevor Pan’s expansive “3 Desert Way” (2006). The delicate, Chinese lantern-esque building sits on a large concrete pad with built-in benches and jutting geometric forms that took Mr. Pan 400 days to construct. While beautiful, large pads such as these caused the school to introduce new footprint restrictions, since leaving the desert as undisturbed as possible is a key consideration.

After passing an old, crumbling foundation, we stop under the stretched canopy of “Brittlebush,” an open-to-the-elements shelter by Simón De Agüero (2010). To access the cantilevered slab containing the bed, one climbs two rungs jutting from a rammed earth wall, snuggles in, then hopes sleep comes before the residual heat from the fireplace underneath dissipates; then again, with the scratchy sounds of critters scaling the walls, it’s possible that sleep here is impossible.

Finally, we arrive at one of Taliesin’s older shelters. “Lotus” by “the great love-master” Kamal Amin, Mr. Lock says, was built in 1963 to appeal to Mr. Amin’s girlfriend, who had issues with desert living. Last year, students consulted with the octogenarian architect to restore it.

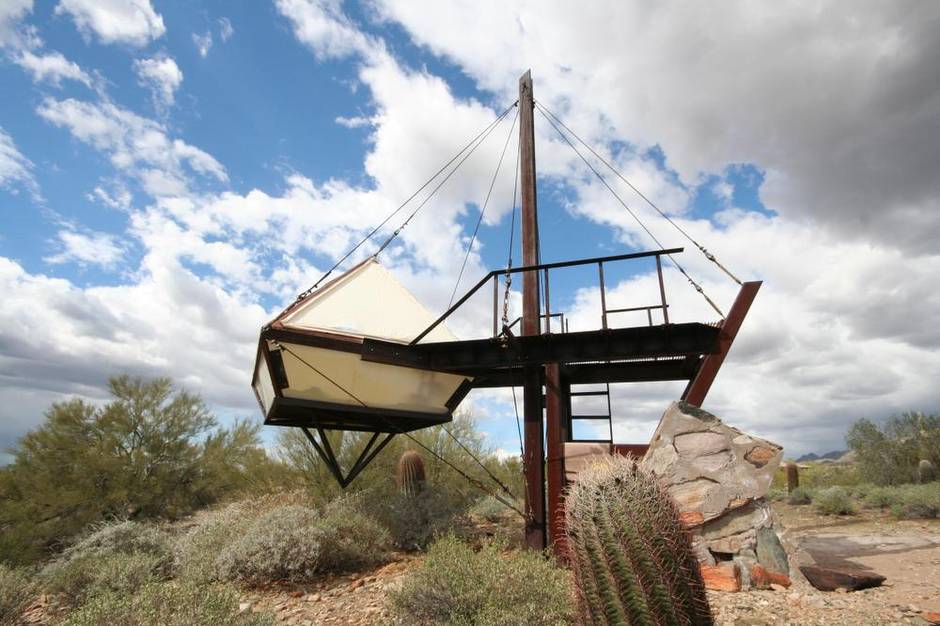

And speaking of girlfriends, “Hanging Shelter” (2001) was built (or “overbuilt,” Mr. Lock says) by Fabian Mantel and Fatma Elmalimpinar as an enticement for co-habitation also. Striking in form, it’s a composition of steel deck, tall mast and buried counterweight to support a hanging, diamond-shaped tent. Obviously, a shelter this complex requires more than the $2,000 stipend students receive; Mr. Lock says it’s common for a bill of 10 times that, so students try to solicit donations from steel suppliers, glass manufacturers, corporations and the like.

David Frazee’s “Miner’s Shelter” (2012), a handsome black box attached to an existing 1980s fireplace – Toronto architect Lloyd Alter described it as a “tiny gem” on Treehugger.com – is less Wrightian and more Miesian, as is the “Glass House” (1979), by Alan Olin, which “has always been inhabited” because “people do love things that are like miniature houses.”

After passing Louis Salazar’s “completely impractical” shelter “Hook” (2002) and one from the 1950s that’s currently locked up for fear it might topple over, we reach the impressive “Ironwood.” While Mr. Lock has called it home for the past year, its original occupant was Chad Cornette, who designed it in 2000 as a V-shaped bridge that crosses a desert wash twice. As we enter, a trapped hummingbird is easily released when Mr. Lock flips a large window over to turn it into a drafting board.

“I think I lucked out,” Mr. Lock says, adding that students interested in living in an existing shelter are asked to come to a meeting after they arrive at Taliesin, and the first one to show up gets first pick, second one gets second pick, and so on – it’s that simple.

What’s not simple is the decision to take on a shelter project in addition to one’s studies, since it’s not a requirement for graduation. Looking through Ironwood’s glass floor at the ruddy wash below and explaining it’s a “highway for wildlife,” Mr. Lock ponders the question. There’s another shelter out there, he says, that many students consider to be “the ugliest” of them all; although it was designed and built in 2001 by Aaron Kadoch, the glass block gives it a very 1980s, Miami Vice vibe.

“I, of course, am falling under its seductive spell,” he says. “Maybe this will be my project, I’m going to make ‘Glass Block House’ cool.”

Yes, seduction comes easily in this desert heat, but so do the scratches and bites.

If you go

Many airlines offer direct flights to Phoenix-Scottsdale from Toronto. Taliesin West offers multiple tour options, some all year long, some seasonal. The Desert “Shelter” Tour is $40 and worth every penny; there are many other shelters to see not mentioned here. “Plan a trip” at franklloydwright.org.

The most appropriate – and fun – place to stay while in Scottsdale is the Valley Ho Hotel, a 25-minute drive from Taliesin in the Scottsdale Arts District, a charming area brimming with art galleries, restaurants, and even a tiki bar. Opened in 1956, the Valley Ho was a celebrity playground in its heyday – Robert Wagner and Natalie Wood chose it to for their wedding reception in 1957.

The Valley Ho was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright apprentice Edward L. Varney, who clearly paid attention when the master was lecturing, as it has many Wrightian touches, albeit with a playful Jetsons-type futurism mixed in. The hotel underwent a restoration and expansion by Westroc in 2004-05. See hotelvalleyho.com

Editor's Note: The author received a discounted media rate for his accommodations on this trip. The provider did not review or approve the story before publication.