Memphis is back. Remember multicoloured sofas with spheres and pyramids for feet, bookcases with jutting shelves in motley laminates? The 1980s Italian postmodernist movement – which thumbed its nose at function-obsessed modernism with loud, over-the-top aesthetics – has seen a resurgence in the past couple years. In 2015, it came full circle. Kartell, the manufacturer of sleek plastic furniture, made it official during Milan design week by decorating its shop windows in the vibrant squiggles and confetti of Memphis patterns. Inside, contemporary chairs – such as Philippe Starck’s Mademoiselle and Patricia Urquiola’s Foliage – were dressed up in eye-popping prints. The brand also debuted a collection of glossy sculptural furniture by Ettore Sottsass, the founder of Memphis who died in 2007.

This renewed interest coincides with the postmodern-inflected trend embraced by many young talents who were barely born during the Memphis heyday. A few weeks after the Milan fair, during New York design week, Anna Karlin displayed rugs and chess-piece stools decked out in a mix of raucous patterns. And, at Colony, a designers’ co-op in Tribeca, New York, Montreal’s Zoë Mowat exhibited Ora, a side table with a double-top; in one version, the upper layer, made of glass, is propped up on the lower brass surface by two sculptural objects, one double-sided marble, the other green-lacquered wood. It looks like a more refined, and functional, descendant of Sottsass’s Park Table from 1983.

Yet, the 29-year-old isn’t beholden to a defunct style. Like many designers around her age playing with pomo, she’s reinterpreting its playfulness with subtlety. “In terms of what we’re seeing,” she says, “it’s not the same subversive, anti-design movement of the 1980s. It’s more embodying a similar spirit – a lively spirit – in terms of the focus on boldness, colour and pattern.”

The Memphis Group was definitely subversive. Its intentions ran much deeper than a desire to unleash wacky, look-at-me furniture on an unsuspecting world. The San Francisco Chronicle has called the aesthetic “a shotgun wedding between Bauhaus and Fisher Price” – albeit a ceremony officiated by Federico Fellini. When its founders, a group of radical designers led by the visionary Ettore Sottsass, came together in 1980, they were rebelling against the rigid rules of modernism. At Sottsass’s Milan apartment, they rhapsodized about what would become the New International Style while listening to Bob Dylan’s tongue-in-cheek lament Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again.

The gorgeous art book Sottsass by Philippe Thomé, released last year by Phaidon, describes the heady months after that first meeting. (Another book, Ettore Sottsass and the Poetry of Things, is due out in September.) Designers including Michele De Lucchi, Matteo Thun and Nathalie Du Pasquier sketched, prototyped and promoted their inaugural collection in the evenings and on weekends – they all had day jobs. In September, 1981, their show at Milan’s Design Gallery attracted more than 2,000 spectators. “We arrived by taxi, understandably excited and terrified,” Barbara Radice – the design critic and Sottsass’s wife – later recalled. “We thought there must have been an accident. We couldn’t even get in.”

The movement had no manifesto of its own. As Radice wrote, “the roots, thrust and acceleration of Memphis are eminently anti-ideological.” Yet that first collection said it all: It mixed high and low materials, including kitchen-grade laminates with Bacterio and Spugna patterns, and it put form before function, presenting multifarious furnishings that collaged textures, shapes and uses. It included Sottsass’s now-famous Carlton room-divider-cum-bookcase, with shelves branching off in all directions, and Masanori Umeda’s Tawaraya boxing-ring bed – even nuttier than it sounds. I encountered it this spring at a retrospective staged by Post Design, the Milan gallery run by the successors of the original Memphis Group.

The excitement soon flamed out. Sottsass tired of the media circus, and the world tired of the movement’s tackier tendencies, and it went the way of teased bangs and neon sweatbands before the decade was over. But now, the aesthetic – and its influence on a new generation of designers – is back in the spotlight. Besides the end-to-end retrospectives in design galleries, the market for Memphis is hot.

The young designers who are riffing on postmodernism, though, are turning down the volume, opting for softer hues and more pleasing material and pattern mashups. They include many New York studios, such as Chiaozza and Ladies & Gentlemen, featured in the trendsetting – and pomo-loving – online design magazine Sight Unseen. The aesthetic is also big again in Europe; the new collection by London’s Lee Broom includes the Drunken Side Table, an off-kilter, black-and-white-striped cylinder balancing a sphere topped with a circular slab that screams Memphis.

The aesthetic is also a source of inspiration for Canadian designers. During Toronto design week in January, furniture designer Khalil Jamal displayed Column, a table made up of 22 layers of felt that can be stacked symmetrically or rearranged into various shapes. He’s now also working on a chair and shelf that similarly experiment with colour and configuration. “Memphis’s use of colour, decoration and shape were a big influence in conceiving these pieces,” he says.

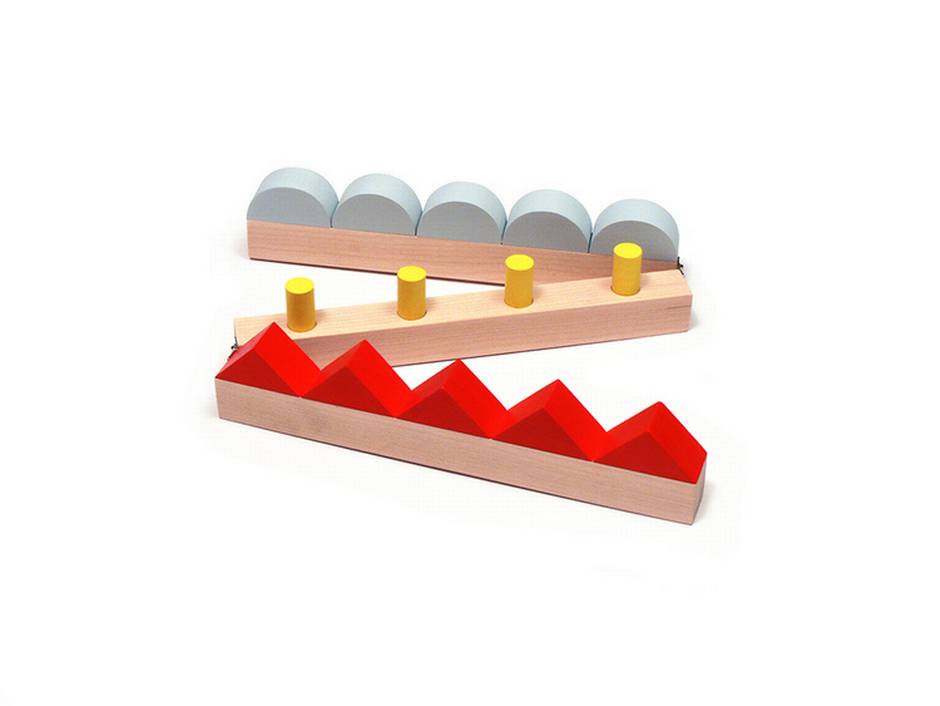

And the movement has captured the imagination of young artists, as seen in some of the offerings up for auction at the Stellar Living event by Toronto’s Mercer Union gallery in May. There, Vanessa Maltese showed off the multihued Ornament Swatch, consisting of three hinged sticks each topped with a different shape: half-circles, pegs and triangles – “a humorous, useless object,” she says, “like a swatch you might reference when deciding on gingerbreading for the roof of your house.” She encountered Memphis six years ago at the St. Lawrence antiques market, where she saw three kitchen tools by the group. “The bread knife had a circle, square and triangle punched out of the blade and each were painted in black, sea foam green and powder pink. I thought they were so ugly that they were beautiful.”

The new Memphis-inflected design is simply lovely – without the ugly quotient – but it’s still an antidote to the sameness of mass-produced furniture. It channels the desire for the hand-crafted, custom and authentic. Eight years ago, when Zoë Mowat began designing, her pieces were a reaction to the white shiny blobs that were big back then. “I wanted to focus on material and simple geometric forms, but with colour. And make people wake up a little bit,” she says. She’s more interested in seeing what happens when different materials – such as lacquered wood, brass and marble – butt up against each other, than in creating a pastiche of inscrutable materiality. Her tactile, self-produced designs, including the Ora mirror, Arbor jewellery stand and Stack lamp, beg to be touched as much as be looked at.

Her affinity lies with the enduring designer (Sottsass), rather than the short-lived movement (Memphis). In fact, Sottsass was constantly innovating, before, during and after Memphis. An exhibit opening in September at the eminent New York design gallery Friedman Benda covers his career from 1955 to 1969; and his sculptural collection for Kartell – six vases, two stools and a lamp, with names such as Colonna (column), Pilastro (pillar) and Calice (chalice) that exemplify his love of blowing up small objects and shrinking down architecture – was actually designed in 2004, when he was 87 years old. Kartell is producing a selection of the pieces today because it now has the plastic moulding technology to do so. As always, Sottsass was ahead of his time.