Blair McMillan and his girlfriend, Morgan Patey , turned back the clock to 1986 – the year of their births – banning all modern technology from their home for a year. The Guelph, Ont., parents embarked on the tech-free challenge last April after their older son, Trey, 5, got hooked on their iPad . Trey had also developed the slightly unsettling habit of identifying aunts and uncles by their brand of smartphones.

“A light bulb went off for me watching the kids at playgrounds,” says McMillan, 27. “The other parents would sit on a bench with their phones not interacting with their kids. I was guilty of it, too.”

The family’s year-long tech detox is a radical version of the less committed experiments North Americans are increasingly dabbling in to tune out the information age. Think e-mail sabbaticals, tech sabbaths , vacations at black-hole resorts where mobile phones are shunned, as well as more precious urban incarnations like the “phone stack” game, which sees friends dining out together place their phones in the middle of the restaurant table. First one to cave and pick up during the meal also has to pick up the tab.

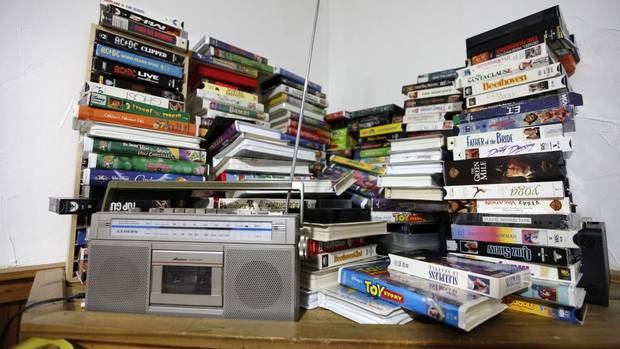

In Guelph, the hiatus is more extreme. The couple shuttered their social media accounts. All tablets, mobile phones and laptops have been banished from the house; they’re locked up at the home of McMillan’s mother. Guests are asked to place their gadgets in a wooden “cellphone box,” where they buzz away through dinner. Relics from 1986 have replaced modern technology. There’s a land line on a bar stool and a Yellow Pages phone book in the kitchen for calls. A pink Panasonic boombox blares Talking Heads, Roxy Music and Wham!, on cassette. Gone is the high-definition cable TV, replaced by a wood-panelled tube television donated to them by a septuagenarian. A set of worn encyclopedias serves as the Internet. In the basement playroom, Trey and his brother Denton, 2, can peruse a towering stack of VHS cassettes and try their hand at Top Gun on the ancient Nintendo system. What they don’t know won’t hurt them.

The family’s trial is up on April 27, and while this mulleted endeavour has earned them reality-TV offers, a New York agent and the label of “that eighties family” in their quiet neighbourhood, they think we’re weird, too.

“Going out in public’s a funny thing,” says McMillan. “You look around and you see everybody on their cellphones.”

“We were at a restaurant recently and a mother and daughter were having lunch,” recalls Patey, 28. “You could tell they hadn’t seen each other in a long time. The entire meal, the daughter was on the phone and the mom was staring at her. There was no communication at all. It’s just the way the world is now and it’s just going to get worse.”

Before the detox, Patey and McMillan also suffered their antisocial moments. He would stream a hockey game on a laptop while group chatting in one room while she watched films on her iPad in another room; occasionally they’d text through the walls. “It’s silly when we think about we did,” says McMillan.

Today, McMillan believes the bizarre experiment – which involves banking with a real live teller and finding a way to develop rolls of film – has actually brought his family closer together. “There are no distractions. We eat dinner together. We sit in our family room on the weekends, Morgan on the couch, I’m on the chair and the kids bring out their toys. Nothing can take us away from the moment.”

The family wanted to take on their 1980s challenge before Trey started Grade 1 and before Apple products slowly became inescapable in his life. There’s a calmness in the house, free of the siren song and constant ping of digital toys. The adults relish not being on call: “When we leave the house, we leave the house,” says Patey . “You’re not getting a hold of us. It’s quite nice.”

There are of course some downsides to their stunt. Without the controlled convenience of text and e-mail, the family has become somewhat alienated. “We don’t talk to our friends as much any more. They all communicate via text and we’re a phone call away now,” says McMillan. “Everyone wants to know what’s going on instantly.”

“You talk to somebody and then it could be months before you talk to them again,” says Patey . “You literally have to sit right by that phone there, pull up a chair and talk. Sitting on the phone for an hour isn’t always convenient.”

Social calls have also shortened. “I think our house scares people away. People walk in here and they have to put their phone away in the cellphone box and they have to talk,” says Patey . “It’s foreign to them to not have any technology for an entire day and not know what’s going on out there. It stresses people out.”

Still, when people do swing by, there’s more to catch up on “because they can’t see our life on Facebook ,” McMillan points out.

What will they do after April 27 when the experiment runs its course? One reality-TV series idea pitched to them was a spin on Wife Swap: the mulleted duo would coach families “totally torn apart” by technology. They’re also contemplating a tech-free bed and breakfast.

“The scariest thing is that we’ll be able to use everything again and maybe we won’t have learned anything and we’ll just conveniently go back to the lifestyle we had,” says McMillan, who would, however, like a moratorium on tech at the dinner table going forward.

Patey’s not ruling out booting up her iPad at the end of the month.

“It’s hard. I hope we can keep a lot of this lifestyle. I miss TV. I would love to get some cable.”