Hands Open

Crying

So Soft Asleep

Wanted to Feel Good

How I Sat

Fist Clasped

I’m Actually Here

Good Fat

Think of You So Much

Alone Is OK

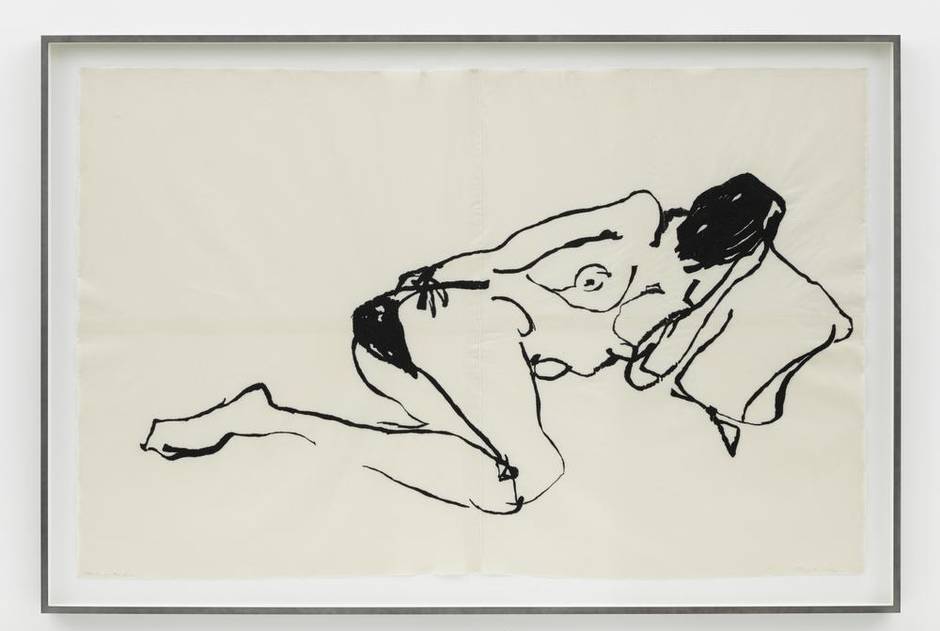

The individual titles, scrawled in her trademark handwriting across the bottom of figure drawings – loose, pooling lines of gouache on paper – read like cryptic thoughts. Gathered into a loose, poetic-like narrative, they leave you thinking Tracey Emin has gone as soft as her body.

The British bad-girl artist, who famously created the art installation My Bed – an unmade one, with stained sheets, used condoms, underwear with menstrual stains and an empty alcohol bottle, short-listed for Britain’s Turner Prize in 1999 – is now 51. She is known for her in-your-face depictions and description of her promiscuous, youthful sexuality; Charles Saatchi, former husband of cookbook author Nigella Lawson, first made Emin famous when he purchased and displayed one of her seminal works – her “tent” installation in 1997. Entitled Everyone I Have Ever Slept With, 1963-1995, the blue pup tent was embroidered on the inside with 102 names, not only those of boyfriends and casual lovers, but also family (her grandmother and twin brother), drinking partners and two aborted fetuses.

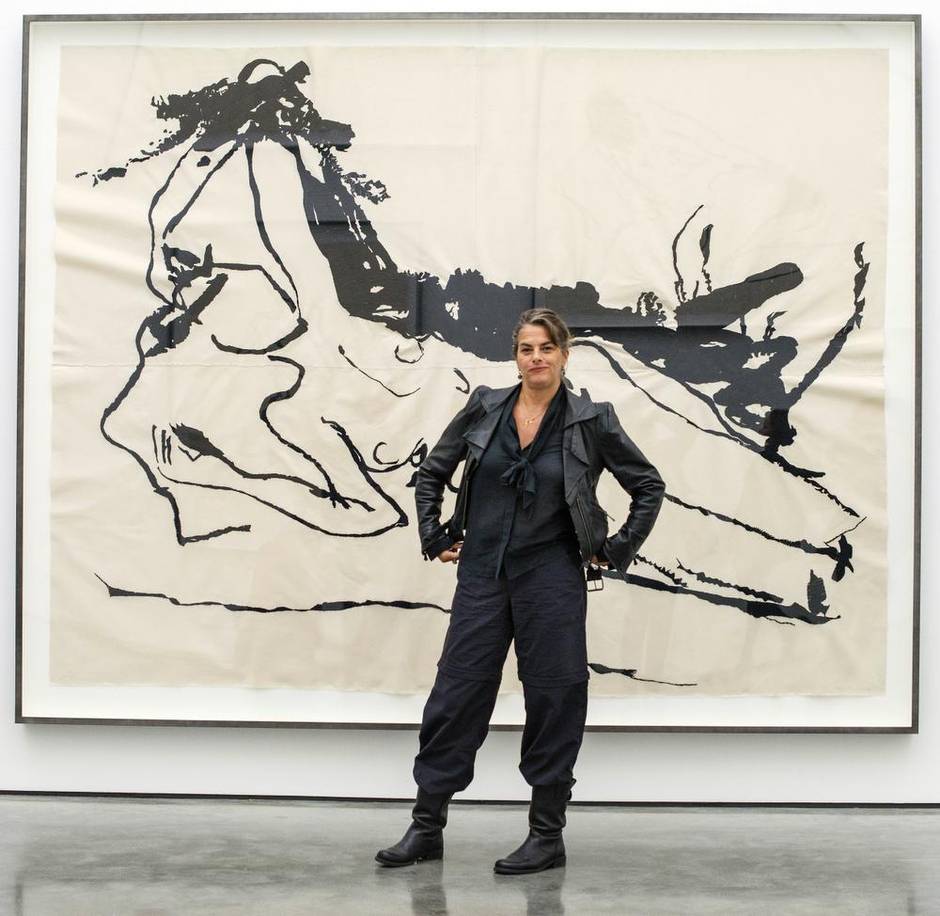

On the floor appeared the words, “With myself, always myself, never forgetting.” But this new, major exhibit, called The Last Great Adventure Is You – her first in five years for influential London gallery White Cube, run by her champion and impresario, Jay Jopling – is being billed as work from a mature Emin; an examination of “the third phase of life.” She wants to come to terms with herself, she explains in an accompanying video presentation, and that seems to involve calm acceptance and sedate appreciation of the lumpy middle and the sagging bosom.

“That’s it?” I thought, wandering through her line drawings and bronze sculptures at White Cube this week. How disappointing. Women and age is a subject as rich as a fattening dessert: such a mix of fear, vanity, loss, serenity, wisdom, freedom, defiance, self-loathing. And there’s so little discussion about it in culture, beyond menopausal comedy shows and the beauty industry’s mission to fix the aging process as if it were a dreaded disease. As a feminist, confrontational artist, surely Emin would force some interesting debate?

I didn’t expect resignation – something Emin didn’t do, not in her youth anyway, when her response to a difficult childhood, sexual abuse, rape and failed relationships was to rise above it with a joyful, defiant spunk. The agony of youth may give way to the complacency of middle age, and acceptance of self is part of it, I suppose, but I felt cheated of some added layer of thought or insight in this show. Might she have encouraged us to mock our own vanity? To move beyond preoccupations with the body? To challenge or expand the tired stereotypes of cougar and crone?

Identity through appearance is so embedded in women’s psyches that “the third phase” is not often a gentle journey into the night. That’s why you have people such as Jane Fonda raving about septuagenarian sex through her face-lifted mask. Emin’s gouache drawings may have a graceful fluidity (she is said to draw inspiration from the draftsmanship of Egon Schiele), but they lack any compelling tension. It’s mawkish, punchless sentimentality. Is there no regret for her choices? No reconciliation of her demons? The self-absorption seems lazy, as if the most profound insight she can offer is that she’s bummed out she’s not getting laid enough.

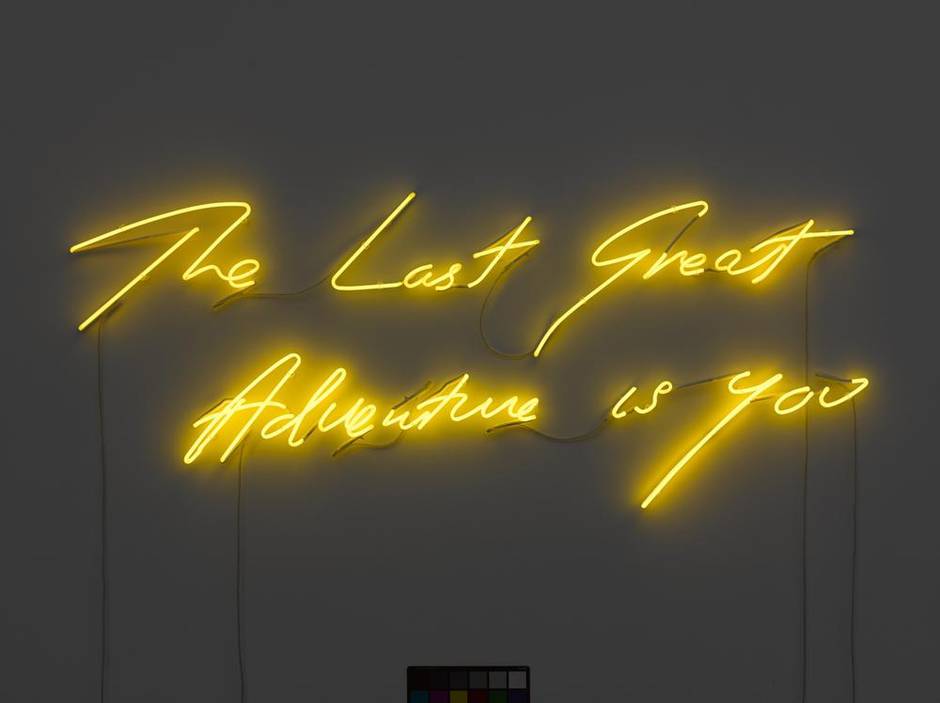

With the exception of large embroideries of line drawings of nudes and some big paintings, the works, which also include sculptures of body parts, are small and somehow tentative, half-finished-looking or half-born as though this new Tracey, this new adventure of self, is not quite certain of where it is headed or what it wants to be. Her bronze sculptures are barely recognizable as human. The neon signs feel clichéd: “The soul will always do what it needs to do,” “Your absence only makes me love you more.” The march to mortality is often portrayed as a soulful journeying, that “rage against the dying of the light”, as Dylan Thomas wrote. Emin calls hers an adventure? It appears more as a decision to stay at home, plonk yourself on a ratty sofa, recline in the nude and look at herself in the mirror in post-masturbation calm.

Rembrandt took on aging as a lifelong subject, painting numerous self-portraits. There’s an exhibition of his late works at the National Gallery in London at the moment, and his depiction of age and a life filled with hardships (bankruptcy, bitter legal proceedings, the loss of his common-law wife and remaining son) is filled with soulful dignity.

Torrid self-absorption has always been Emin’s subject. The Last Great Adventure Is You is not about you or me; it’s about her. She wrote in Strangeland, a collection of her writings about her hardscrabble life in Margate, that “I thought with my body.” By that, she meant dancing and drinking and shagging almost every man and woman in sight. She had left school at 13, the same year she lost her virginity by rape, and her art, after attending Maidstone College of Art and the Royal College of Art, combined a weird, sentimental sweetness alongside the anger and defiance. She would say and do anything. Once, she was embarrassingly drunk on TV. She would make bright neon signs saying things such as, “Is anal sex legal?” or “Fuck off and die you slag ” (written in her scrawled handwriting), as if needing to emblazon the world with her words, her voice, of “illuminated honesty” as one critic put it, and feminine angst.

And you had to pay attention to her for the courage of her vulnerable self-revelation. It was feminist and raw. Her confrontational style underscored her desire to overcome her hardship. She was an artist of prurient, morbid curiosity at the dawn of the digital age in which everyone now confesses and displays every thought, every body crevice, every behaviour. At the time, her one-woman investigation into dark sexuality was fresh. She was that archetypal, tortured young thing, consumed with (and liberated by) her physical self: anorexic, desirable, promiscuous, exhibitionist; a heroic victim who drew loving attention to her wobbly self.

And love her people did – and still do. One female visitor at the gallery described her as “a powerful icon for women.” She represented Britain at the 2007 Venice Biennale. In 2011, she was made a professor of drawing at the Royal Academy. She owns several houses, including a £4-million (about $7-million) house and studio in London with a pool in the basement and 360-degree view from its lavender-planted roof, a pad in St. Tropez, another in New York and Miami. Works from The Last Great Adventure Is You are on sale for between £17,000 and £220,000 (approximately $30,600 and $397,000). The enfant terrible is now an establishment fixture.

The show has received mixed criticism, which is not surprising. She is a polarizing figure. “A masterclass in how to use traditional artistic skills in the 21st century,” crowed the Guardian, calling her studies of the female form – all her own self – “an attack on the patriarchal temple” of male artists who have traditionally depicted the beauty of the female nude. Others have called the show “vulgar” and her drawing skills “second-rate” – evidence of little more than the “cottage industry” of Emin’s output, which includes T-shirts and home wares.

For me, the one telling comment on middle age was in the forecourt of White Cube. Called Roman Standard, Emin’s sculpture is a 13-foot, thin pole with a small bird on the top. I would have missed it if she hadn’t mentioned it in the video presentation. But it is poignant – a quiet statement of fragility and delicacy, of fleeting presence and the invisibility of middle age for women. And yet there it is, inspired by a Roman display of masculine power and aggression, standing tall.

She may like to still suggest that vulnerable, girlish mess of anxiety. “Oh, God, it’s me giving birth to myself – or maybe it’s me saying goodbye to something,” she explained to one media outlet, when asked about the meaning of her large half-finished painting, Devoured by You, which depicts splayed legs (if you can figure out the scribbly body parts) and an outline of a female form in red.

But the tortured, artistic stance comes off as disingenuous, just a knee-jerk, media-practised expression of her famous public persona. The wobbliness of her being is now, prosaically, in her derrière.

The Last Great Adventure Is You runs at White Cube in London until Nov. 16.