It’s haute couture week in Paris, and I fully expect news of another revival. But which forgotten fashion label will it be this time?

Karl Lagerfeld managed a revival expertly. “When I took on Chanel, it was a sleeping beauty,” the late designer said of joining the brand in 1982. And you can’t blame a risk-averse company for trying to capitalize on past success – it’s precarious to invest in a new designer with no name recognition, and Lagerfeld helped build Chanel into a US$10-billion business. Hence the strategy of taking a dormant name, leveraging its history, dusting the runway with a bit of its mythology and maybe boosting fragrance sales while you’re at it.

After 90 years of dormancy, Paul Poiret, for example, the once-powerful heritage French brand, was recently revived by South Korean fashion group Shinsegae. Likewise, after buying a majority stake in Patou last year from the holder of its fragrance licence, luxury conglomerate LVMH is set to revive the historic French haute couture brand with young designer Guillaume Henry at the creative helm. Both historically important houses, but also both bygone couture brands nobody is clamouring to wear.

Vaguely familiar, fondly remembered ideas retooled and rebooted into lucrative legacy franchises have worked well for Hollywood. But in fashion? It’s trickier.

Five years ago, for example, The Weinstein Company bought the Charles James label with plans to relaunch, but repeatedly stalled and last year quietly put the brand up for sale. A similar fate hit the attempted resurrection of fabled Schiaparelli by Tod’s Group chair Diego Della Valle, which has yet to find its footing beyond the red carpet, and is now on its fourth designer since 2013.

A successful revival is about more than blowing the dust off the box and tweaking a logo. It has to go beyond the cliché of motifs and monograms easily slapped on handbags, shoes and dresses. The challenge is to make not just the idea of the brand relevant, but to design clothing that resonates today.

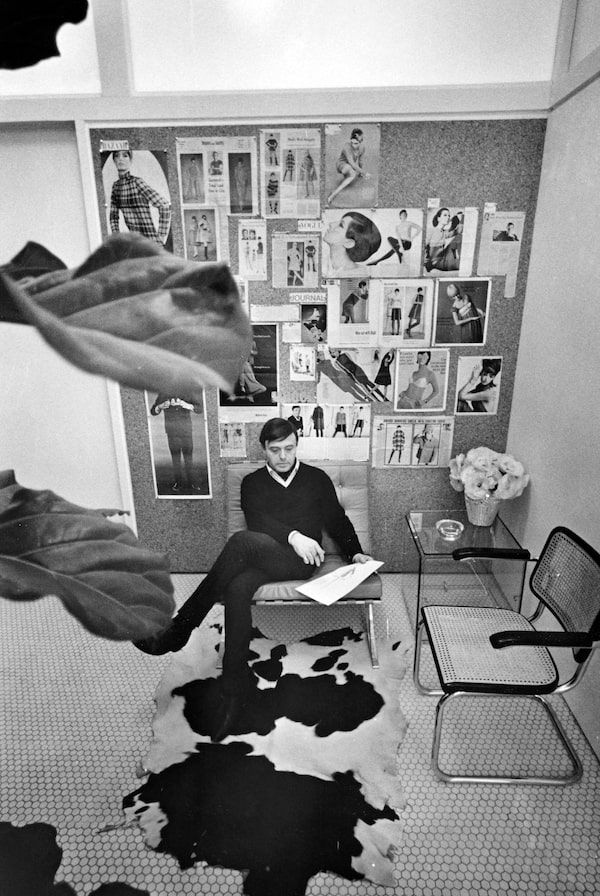

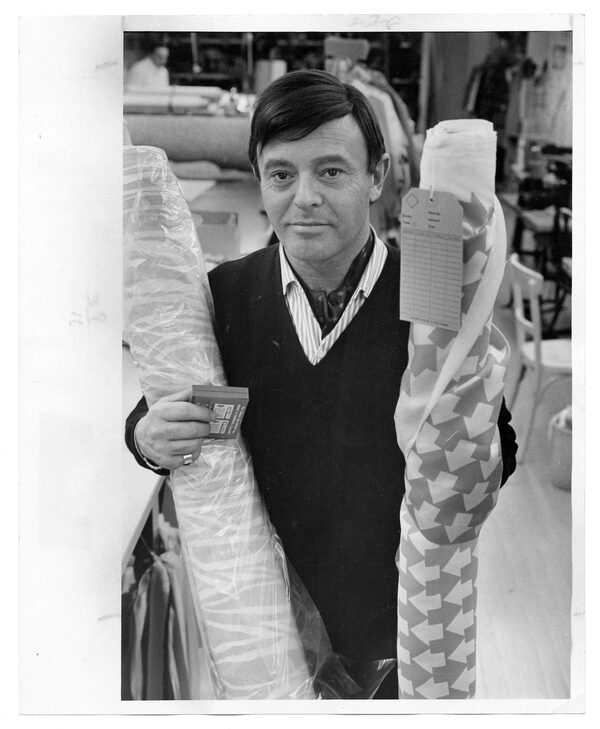

Rudi Gernreich at his office in Los Angeles, 1966.courtesy of Demont Photo Management & Fahey/Klein Gallery Los Angeles, with permission of the Rudi Gernreich trademark./Handout

With some brands, such as Celine, that’s easier, but other revivals seem anachronistic to the prevailing mood and what we need. There is, however, one revival that seems perfectly poised to succeed, and it’s that of visionary provocateur Rudi Gernreich, who died in 1985. His heyday in the 1960s was a time of similar cultural tumult.

The Austrian-born designer’s inclusive ethos was shaped by the experience of fleeing the Nazi regime and facing discrimination because he was Jewish and gay. After emigrating to the United States in 1938, he became one of the founders of the Mattachine Society, one of the first gay-rights organizations in the United States, to whom he left the intellectual-property rights of his estate.

Through an arrangement with the estate, an entrepreneur has quietly reintroduced the label at retailers such as Net-a-Porter and SSENSE. It’s been so stealth, in fact, that in spite of legendary stylist Camilla Nickerson’s work as co-artistic director on the relaunch, even dedicated followers of fashion still don’t know about it. But that hasn’t stopped the clothes from actually selling (unlike the runway fanfare of luxury French brands.) It figures: Gernreich was resolutely anti-couture, and rather than set up a Manhattan salon – as many of his contemporaries did – he went west and became part of the artistic California modernism scene.

Early on, he saw fashion as a vehicle for social change and political commentary. In the same year Betty Friedan’s second-wave feminist landmark The Feminine Mystique was the bestselling non-fiction book, for example, Gernreich made a political statement with pantsuits inspired by Marlene Dietrich (several years before Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking). And in that same year, 1964, he released the monokini, a close-fitting bottom with two straps to wrap around the neck. Denounced by the Pope and banned in several countries, the controversial topless swimsuit remains Gernreich’s most notorious garment.

Gernreich saw fashion as a vehicle for social change and political commentary. Here: Peggy Moffitt in a Nehru ensemble designed by Gernreich, Resort 1965 collection.ourtesy of Demont Photo Management & Fahey/Klein Gallery Los Angeles, with permission of the Rudi Gernreich trademark./Handout

The monokini was about body positivity, says Dani Killam, co-curator of the exhibition Fearless Fashion: Rudi Gernreich, on view at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles until Sept. 1. “It was so women could swim unfettered and in comfort. Gernreich saw fashion as a liberating force,” Killam says, “to challenge conventional notions of beauty, identity, gender and body type.”

The fashion radical had a hand in engineering a total lifestyle aesthetic and designed everything from tea towels to fragrance to gourmet soups, Killam adds. “I think it was his innate creativity. He didn’t feel restricted to one medium at all.”

Everyday ideas that were considered avant-garde at the time are, today, taken for granted because they populate our closets (or should). He eliminated linings, used alternative materials (“like a dog leash for a belt or bike springs for the neckline of a dress”), championed unisex looks and pioneered sheer unstructured bras – the no-bra brassiere that’s now Calvin Klein’s stock-in-trade – and sold over a million of them, marketed with the tagline ‘Rudi sets you free.’

Gernreich eliminated linings, used alternative materials ('like a dog leash for a belt or bike springs for the neckline of a dress') and championed unisex looks.courtesy of Demont Photo Management & Fahey/Klein Gallery Los Angeles, with permission of the Rudi Gernreich trademark./Handout

Other Gernreich innovations include – with deepest apologies for Borat’s version – the thong swimsuit, trademarked in 1974 (“You should forget what you are wearing, and enjoy yourself,” he said). His lack of shame about nudity, through clothing cutouts and use of unusual sheer materials, was also ahead of his time.

Gernreich may have also anticipated the most inclusive fashion phenomenon of all: trendlessness. “What is happening today is most curious,” he wrote of his anything-goes philosophy to buyers in the invitation to his fall 1958 collection. “No waists, high waists, low waists, slimness, fullness, barrels, triangles – and all of it is right. It is not a silhouette, but an attitude which is the important change.”

Throughout Gernreich’s success, his love-hate relationship with the fashion industry persisted. “Fashion, as we know it, is dead,” he declared after returning from a self-imposed sabbatical in 1971, when asked to comment on the industry relative to the state of the world; by then, he felt the key condition of fashion should be reality.

That year, his military-inspired collection was created in reaction to the Vietnam War and, in a presentation staged not long after the Kent State University shooting, Gernreich styled models with dog tags and rifles as further commentary not only on the general discontent about war, but the prevailing fragility and femininity of waif-like models of the day.

“By reality, I mean the use of real things: blue jeans, polo shirts, T-shirts, overalls,” Gernreich further explained at the time. “Status fashion is gone. What remains? Something I am obliged to call authenticity.”

Visit tgam.ca/newsletters to sign up for the weekly Style newsletter, your guide to fashion, design, entertaining, shopping and living well. And follow us on Instagram @globestyle.

Nathalie Atkinson

Nathalie Atkinson