John Ware arrived in Canada as the Prairies were being dotted with homesteads, when Calgary was a collection of tents and clapboard buildings without a rail station, a mayor or even 500 people. Mr. Ware loved the openness of the foothills. The black cowboy, who had been born into slavery in the American South but by then was long a free man, crossed the border at the rear of a cattle drive and never left.

From his arrival in 1882 to his death in 1905, the tall, bearded horseman and rancher helped shape the territory that would become the province of Alberta. He battled 19th-century racism to become an integral member of the almost all-white ranching community of the day. It was in Canada that Mr. Ware found a permanent home and family, becoming a regional folk hero in the process.

Decades of myth-making mean Mr. Ware has been credited with Paul Bunyan-like acts of strength, such as pulling a democrat carriage across the prairie when his two horses were killed by a lightning strike. But the retelling of the John Ware story – with a focus on the man rather than the lore – has become a life's passion for Calgary author and historian Cheryl Foggo.

Now, she hopes her National Film Board of Canada documentary – currently in production – will bring Mr. Ware to a broader Canadian audience – and that the story of his life will be a revelation for others, the way it has been for her.

"It is time for an update. And it is time for the story to be told from the perspective of a person of African descent," Ms. Foggo says.

The truth about Mr. Ware is no less epic than the myths. He pioneered new agricultural techniques at his ranches. He walked across the backs of cattle in crowded stockyards. He was physically strong – able to ride the wildest bucking horses and wrestle steers onto their backs with his powerful grip. He once confronted a racist Calgary bartender by throwing him over the counter. He also endured the harsh climate and back-breaking work of sod busting, the flooding of his family's cabin and the deaths of his wife, Mildred, and one of his children.

Ms. Foggo says Mr. Ware's early presence in the West makes him an unusual figure in Canadian black history – which is usually focused on Ontario and the Maritimes – and shows that settlement was more diverse than most people think.

"It helps us to understand that our settler history was multiracial going back to the earliest times of contact with Europeans here," she says, adding that Mr. Ware was not a lone black figure on the Prairies in his day.

As the director and writer of John Ware: Reclaimed, Ms. Foggo has three aims: To say something new through DNA research and other sleuthing about his early life and where exactly in the American South Mr. Ware came from; to tell more about his life in Canada; and to explore her own roots and Mr. Ware's connection to her as a black woman in Alberta.

The film is pegged for a late 2018 release. Filming in Alberta is ongoing, and the U.S. work begins this spring. Rodeo star Fred Whitfield depicts Mr. Ware in scenes filmed in Calgary and at one-time Ware family ranches in the Millarville and Gem/Duchess areas of Alberta. Author Lawrence Hill and Alberta singer-songwriter Corb Lund, along with others, will narrate anecdotes about Mr. Ware's life.

Mr. Ware's beginnings aren't clear, but he was born between 1845 and 1850, in the dying years of slavery in the United States. As a young man, he worked in Texas and eventually headed north. He was in Idaho when he got a job to help bring cattle to Canada.

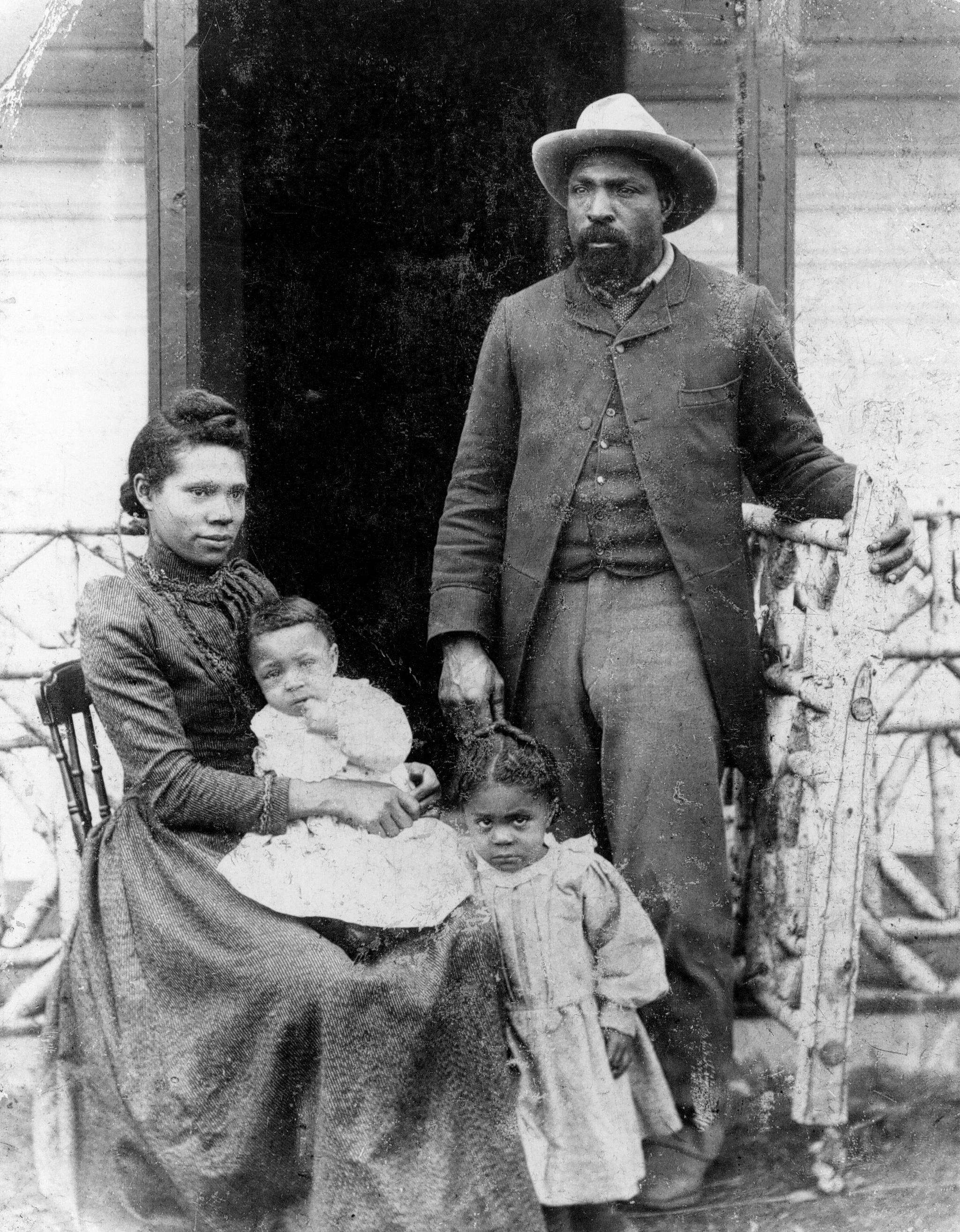

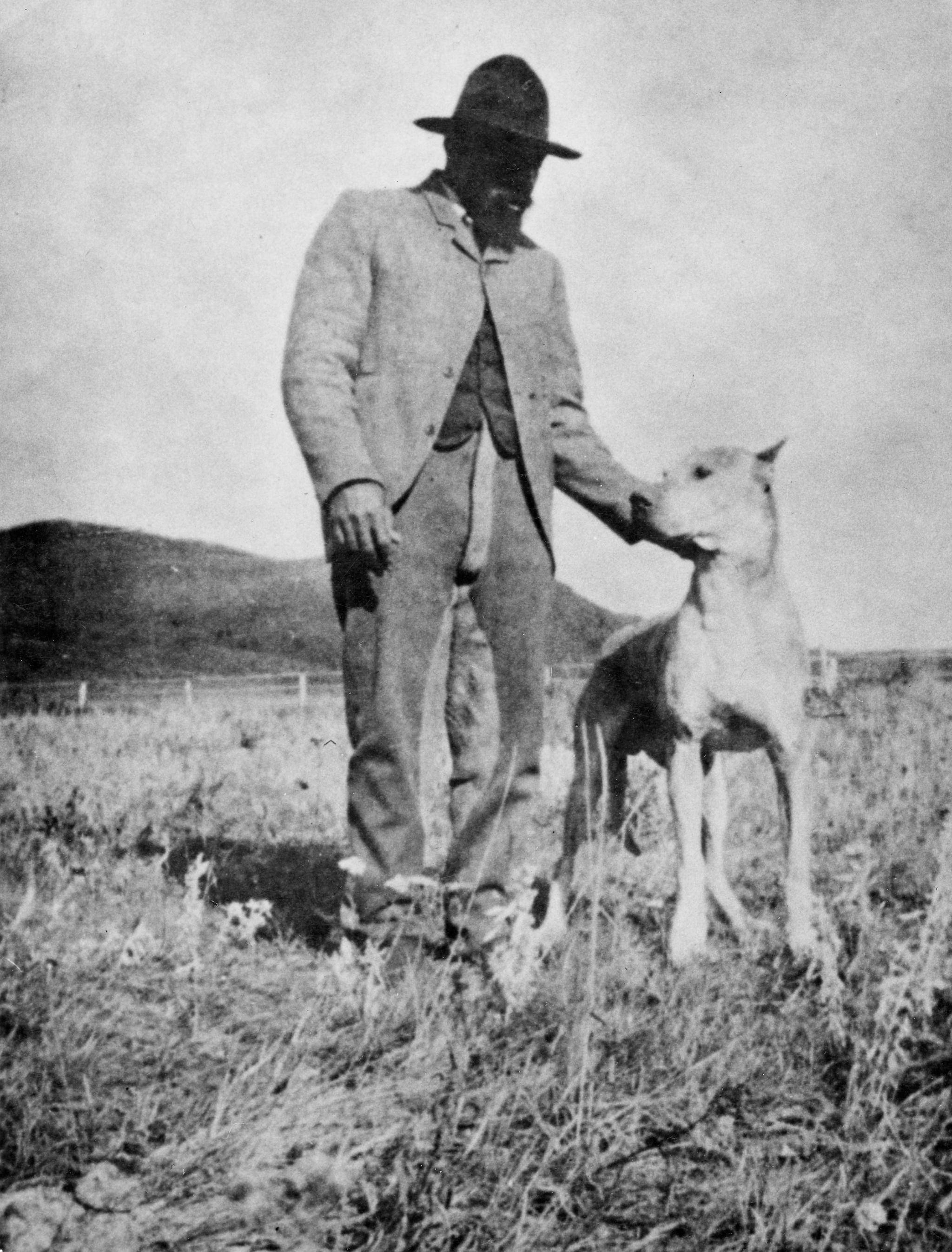

John Ware’s ranch in Millarville, Alta, 1896.

Collection of Glenbow Archives

Ms. Foggo says Mr. Ware thrived in the small ranching community south of Calgary due to his abilities with horses and cattle. But he was also known as a good neighbour and was a natural leader. In a 1956 interview, his daughter Nettie said her father "loved people, to talk, to dance and to play tricks. He was afraid of nothing but snakes."

He was one of the first ranchers in the area to develop irrigation systems and was an early adopter of dipping cattle in a parasiticide that prevents mange – a burrowing mite disease.

"His ranch was a focal point for the treatment of mange in cattle," Ms. Foggo says.

Through the film, the director also wants to explore Mr. Ware's relationship with Indigenous communities. She believes Mr. Ware met Crowfoot, the famous Blackfoot chief, in 1885.

In Canada, Mr. Ware often had to fight racism – sometimes literally. At one point, he asked the government why he was being charged almost twice the price for land that his white neighbours were paying, Ms. Foggo says. A legendary story came from Joe Standish, a ranch hand employed by Mr. Ware, who said that when confronted with a Calgary hotel bartender who refused to serve him and called him a common derogatory term, Mr. Ware "dumped him across the counter and served drinks to everybody." The bartender called the police.

Mr. Ware died in early September, 1905, when his horse tripped in a badger hole and fell on him. It was not long after the death of his two-year-old son, Daniel, and half a year after Mildred had died of pneumonia and typhoid. Now orphans, their five other children went to live with their grandparents. Mr. Ware's funeral, held two weeks after Alberta became a province, was reported as the largest gathering in Calgary to that point.

"People really did come from hundreds of miles around, and there was a genuine outpouring of grief," Ms. Foggo says. "He had such a big impact on people that his neighbours and the other ranchers of his time – and the descendants of those people – have just never let the story die."

Ms. Foggo's own history comes from another little-known piece of Canadiana: Her great-grandparents came to Western Canada with hundreds of other black families from Oklahoma in the years shortly after Mr. Ware died. As Oklahoma gained statehood in 1907, segregation and disenfranchisement laws were passed – and moves to further codify racism spurred violent attacks on black communities. An increase in the number of lynchings in Oklahoma coincided with a Canadian government push to attract U.S. immigrants to the Prairies, and some black families chose to move north.

The window for immigration to Alberta or Saskatchewan was short-lived, however, as the Canadian government began receiving complaints from white settlers.

"Discriminating against blacks through medical examinations and depriving potential black settlers of immigration material were haphazard methods […] and Canada eventually sent two agents to Oklahoma to dissuade blacks from migrating," writes historian R. Bruce Shepard . "Their work was highly successful, and by the fall of 1911, the black migration from Oklahoma to Western Canada was coming to an end."

Ms. Foggo, 61, was born and raised in Calgary. She grew up in what was then a mostly white city where she felt "invisible." She has no memory of a single positive representation of black people in the novels she devoured in childhood – instead, she remembers that her school library had a copy of the derogatory The Story of Little Black Sambo. But she and her brother loved the Calgary Stampede and cowboy culture.

At 11, she learned that John Ware the famous Alberta cowboy was black – and it changed her life. "It was an incredibly healing situation for me," Ms. Foggo says. "It changed my perspective on our place in this part of the world."

Young black men who have seen her play, John Ware Reimagined – first performed in 2014 – have a similar reaction, she says. It makes them feel more comfortable about wearing western gear at the Stampede.

"They have that moment of, 'Once a year when I have to put on that cowboy hat for my office party, I am not separating who I am as an African person from my identity as a Western person or as a Calgarian.'"

There's a mountain ridge named for Mr. Ware, as well as two creeks, a Calgary junior high school and a building at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology. Mr. Ware was the subject of Prairie historian and author Grant MacEwan's 1960 book and was featured on a postage stamp, in tandem with Nova Scotia's Viola Desmond, issued for Black History Month in 2012. (Ms. Desmond will also grace the new $10 bill next year.)

Still, Mr. Ware's story is not widely known in Canada. Ms. Foggo thinks this is because his story is old history, in Canadian terms, and Western Canadian history generally receives less attention than that of other parts of Canada.

She says the story of one of Canada's pre-eminent black pioneers deserves more recognition. She often thinks of the day when Mr. Ware arrived on the land that would one day be the Bar U Ranch National Historic Site near Longview, Alta., shortly after he arrived in Canada. She imagines he was "struck by the beauty and openness" of the place.

"I always envision him on a horse, looking down over the valley with the foothills just rolling out behind, and then the mountains. … He may have thought here he would have the opportunity to become a rancher – and not just remain a cowboy."