John de Ruiter's signature stare in action. These ‘silent connections’ with his followers can sometimes last for hours at a time, producing intense visions or near-death experiences.Footage excerpted from College of Integrated Philosophy video

This article was originally published on Nov. 25, 2017.

There was a cup of coffee on her desk, growing cold. There was her wallet and her cell phone, her purse and her winter coat, a framed picture of John. The face she had stared at for countless hours, light hair and clear blue eyes, a gaze that felt as though it could unlock the universe itself.

Anina had moved across the world to be close to John de Ruiter. Four times a week, she and hundreds of others filled the long rows of chairs at The Oasis Centre in west Edmonton, staring silently at him for hours as he sat beatifically under a beam of light, staring back.

He was their guru and teacher, to some even a saviour, a humble messiah they called simply “John.” They left their lives and families to be with him, devoted themselves completely to him and his teachings.

He arranged their marriages and relationships, their jobs and homes, gave them counsel and made their decisions, their lives winding ever more tightly around him while he drew from them their time and their labour, their money and their love. They were Johnites or Oasis, sometimes The College, or just “the group.”

Anina’s mother and sisters struggled to understand. Like others on the outside, they thought it was a cult or a sect and they wondered about de Ruiter’s motives and his power. They’d seen his followers sitting rapt and silent while he spoke what, to Anina’s family, sounded like gibberish.

They saw how Anina had changed. How when she talked about him, she adopted his mannerisms and tone, her face becoming distant and her voice sleepy and soft, almost like an entirely different person than the one they had known.

They weren’t the only ones with questions. There had been allegations de Ruiter had sex with married female followers, stories about the break-up with his first wife and his relationship with two beautiful blonde sisters, who later filed court documents saying he was nothing more than a manipulator and a fraud.

Some former followers believed they’d been brainwashed or hypnotized while in the group, targeted with disturbing “psychic violence” when they left.

But though Anina’s family worried, John seemed to help her and give her balance, and they didn’t want to lose her altogether. If forced to choose, they knew, she would choose him.

Anina was one of hundreds of followers who sat silently with John de Ruiter, staring at him in the hope that he would stare back.Family photo; David Maurice Smith/Oculi

Despite her devotion, Anina didn’t always understand the things John did, the things he called on her and others to do. In the winter of 2014 she found herself increasingly confused and questioning, even as she tried to push those feelings aside.

She knew doubting, even in oneself, showed a lack of faith. In true belief, there were no questions.

“Part of me wonders why John entrusted such teaching to me when it is likely to have me spinning,” she’d written in her diary, a few weeks earlier.

“But I am able to not spin. I am able to be clear. He said I am really learning. Don’t mix levels. With John you will never have less difficulty. He will always give you more.”

It was Saturday, March 22, 2014. There was an event that night that Anina had marked in her calendar as “Party with John.” But she offered her ticket for sale on the group’s private message board instead.

Then she left her cup of coffee and her wallet, her cell phone and her winter coat, her framed picture of John de Ruiter with his eyes as vast and blue as heaven, and headed into the darkness of a cold Edmonton night.

John de Ruiter was a shoemaker who turned to preaching in the 1990s. ‘Blue-eyed savior: Followers of this charismatic guru say he’s the real thing and Edmonton may be the new Jerusalem,’ said one headline about his rise to fame and his growing base of devotees.Family photo/Saturday Night magazine

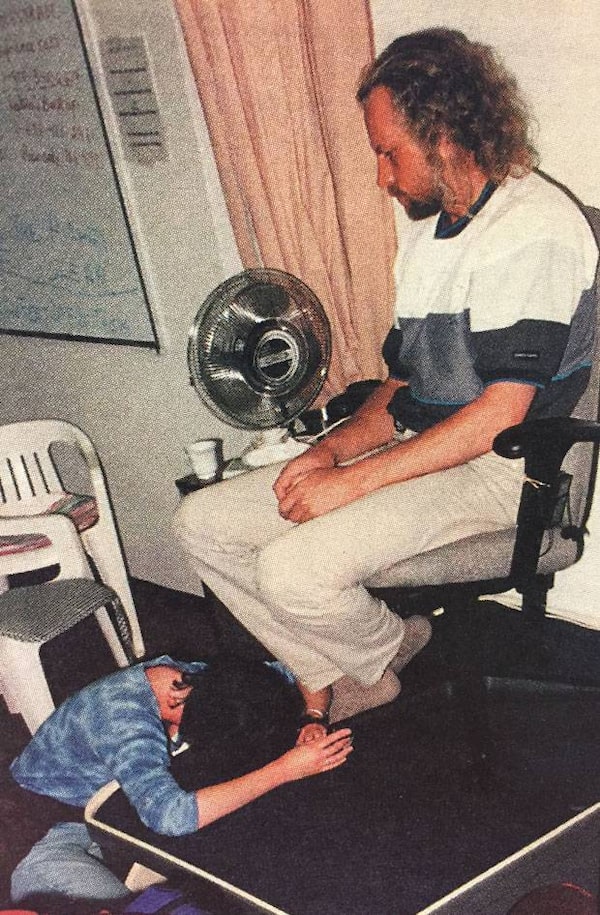

One of de Ruiter’s followers lays herself at his feet. In an intense and intimate environment, it is not unusual for both male and female followers to believe they are in love with de Ruiter.Family photo/Saturday Night magazine

The story goes that John de Ruiter was 17 when he had an awakening, a “flowering inside that made everything in this existence pale in comparison,” then disappeared as quickly as it arrived. The story goes that it took several years of searching for him to find it again, but once he did, it would change everything. He was born in Saskatchewan but grew up in Stettler, Alberta, one of four children of Dutch immigrants, the son of a shoemaker who later took up the craft himself. He met his first wife, Joyce, in 1981 after walking into the Christian bookstore where she worked. He was 22 years old, tall and handsome. She would later say she was drawn by his eyes.

He spent some time in Bible school and later preached at Edmonton’s Bethlehem Lutheran Church, but he clashed with church leadership and strained against the bounds of the established institution. During one sermon, he stood weeping, repeating “God wants to set you free.” Another day he didn’t deliver a sermon at all, telling the congregation, “There’s no word. God has no word for you.”

But delivering his testimony to church leaders he spoke for nine hours straight, and those present knew they’d witnessed something exceptional. When he left the church, a handful of couples followed. He began preaching to them in his home, and soon, they started giving him money.

In 1996, he gave up shoemaking, and by the next year the first news stories began appearing. “Messenger of Beingness: Believers think Edmonton man is conduit from Jesus Christ,” one headline read. “Blue-eyed savior: Followers of this charismatic guru say he’s the real thing and Edmonton may be the new Jerusalem,” read another.

He was an unlikely messiah, a long-haired man from rural Alberta who liked monster trucks and drove a motorcycle. But his following grew into the dozens, then the hundreds, and their devotion intensified. Sometimes his followers wept and clung to him, kissed his feet, supplicated themselves before him on the floor.

In early interviews, de Ruiter described meeting Jesus on a highway in Alberta, and said Jesus then appeared to him thousands of times and “transferred who he is over to me to do as he did.”

But before long de Ruiter’s preaching drifted toward a more new age message, his second awakening becoming not a meeting with Christ but an experience of being “re-immersed in the benevolent reality of pure being.”

He also adopted the approach for which he would become known: Prolonged periods of staring and “silent connection” with his followers. During the staring sessions, some who looked into his eyes had intense visions and hallucinations, transcendent and even near-death experiences. Sometimes de Ruiter would stare intently at one person for half an hour or more, his gaze never wavering.

From early gatherings in his Edmonton home he moved into the aisles of a Whyte Avenue book store, then rented strip mall office space and began holding four meetings a week, with hundreds of followers paying $2 a meeting to attend. Pamphlets called him “the living embodiment of truth,” and promised, “John de Ruiter lives in total surrender. John knows what is actually true. John can reveal to you who you really are.”

His powers, whatever they were, proved profitable. A news story at the time said the congregation was supporting him and Joyce and their three children, and his following continued to grow.

By the late 1990s, de Ruiter’s message was available for purchase through a catalogue of cassettes and videotapes, and he was holding seminars and retreats around the world, recruiting new followers who began moving to Edmonton to be near him.

Among them was Jeanne Parr, a retired CBS broadcaster from the United States, who rented an apartment in Edmonton and began producing videos for de Ruiter. Her son, Chris Noth, then a star of popular TV shows like Law and Order and Sex and the City, sometimes joined her in Edmonton.

Dr. Stephen Kent, a University of Alberta sociology professor specializing in alternative religions, was keeping a close eye on de Ruiter and the group growing around him. As a young man in university in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dr. Kent had watched with fascination the rise of groups like Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church and The Children of God, and had devoted himself to the study of their structures and successes, the power he saw in them to transform people and rob them of independent, rational thought. In de Ruiter, he saw the beginnings of a powerful movement, even the seeds of a new religion.

Dr. Stephen Kent warned in the de Ruiter group's early years that 'John has embarked on a dangerous path, one that promises great rewards but can lead to terrible tragedy.'Jana G. Pruden/The Globe and Mail

Meeting with de Ruiter and his inner circle in the early years, Dr. Kent urged them to build safeguards against the temptations of power and devotion, to be cautious with psychologically troubled converts and ensure followers maintained the right to question and criticize de Ruiter.

In some groups Dr. Kent had studied, people suffered serious psychological harm, and the dynamics between leader and follower could be extremely dangerous, even deadly. He noted that even with pure intentions, unchecked power and influence can be treacherous.

“John has embarked on a dangerous path, one that promises great rewards but can lead to terrible tragedy,” Dr. Kent warned in the Calgary Herald in May of 1997. Two months earlier, 39 members of Heaven’s Gate had died in a mass suicide in California based on their leader’s heartfelt belief they could leave earth for a spacecraft.

Questioned then about the potential for misuse of his own power, de Ruiter said it was impossible.

“I love the truth more than my own life,” he told a reporter at the time. “At the heart of truth there is no interest in power. There is just the love of being.”

Left: John de Ruiter and his wife, Joyce, are married in 1982. Right: Joyce embraces her husband in 1998, the year before he announced he would take two additional wives from among his followers.Family photo/Saturday Night magazine

On the last days of December, 1999, on the eve of a new millennium, Joyce de Ruiter sat before a room of her husband’s followers and stared deep into his eyes for the last time.

The confrontation that followed was the culmination of a series of conversations in which de Ruiter told her that after 18 years of marriage, he now believed he’d been spiritually called to have three wives, each one “a complete physical, emotional and sexual relationship.”

The new wives were to be Benita and Katrina Von Sass, beautiful blonde daughters of two of de Ruiter’s wealthy and devoted supporters. Both women – Benita a law student, and Katrina a former star of Canada’s Olympic volleyball team – had moved to Edmonton, and were spending increasing amounts of time with de Ruiter and his family.

The von Sass sisters, Benita and Katrina.Instagram, The Canadian Press/COA/Scott Grant

Joyce had questioned her husband about the relationships twice in front of the group. On the third occasion, she began reading aloud a letter she’d written.

“I am the only one who loves John the man. Everyone else loves John the god,” she read. “My sweetie, you are not god, you are not deity. You, more than anyone, have been sucked into a powerful deception.”

“Sex with Benita and Katrina is not truth,” she told him. “Can you just, for a tiny moment, look at what is happening to you?”

She left the meeting alone.

In the months that followed, the couple’s rift became front page news, notable not only because it offered a glimpse into the dynamics of the group and its enigmatic leader, but because of the questions it raised about de Ruiter’s teachings and behaviour.

In a story headlined “Sex and the sect,” de Ruiter admitted and defended his relationships with the von Sass sisters, saying they were not affairs because of his deep spiritual bonds with the women.

“To me, it’s not infidelity. It’s not unfaithfulness because my heart is still completely with Joyce,” he was quoted as saying then.

He assured his followers,”It didn’t have to do with their looks, their appearance, their heart, their age. Didn’t have anything to do with any kind of compatibility. It only had to do with what arose from within my innermost.”

But urges of the innermost weren’t enough of an explanation to appease everyone, least of all Joyce, who saw it as proof her husband was neither the man she’d once known, nor the messiah he now claimed to be. She left the group, initiated divorce proceedings, and took part in anti-cult counselling in the United States to try to make sense of her experience and feelings.

The situation was also a turning point for the sociologist Dr. Kent, who until that point had regarded the group with a leery eye, but had seen nothing that directly caused concern. But a leader using divine claims to take selective sexual partners –especially rich and attractive ones –was something he’d seen before, an all-too-predictable pattern that could indicate an abuse of power for the pleasure of the leader.

The situation also left some of de Ruiter’s followers disappointed or confused, if not exactly critical. One man, an American psychiatrist who had taken a leave from his New York practice to move with his wife to Edmonton, told a reporter he was bothered at first but later saw it as comparable to Jesus and Buddha putting their spiritual enlightenment before the good of their families.

Others, like the former CBS correspondent Jeanne Parr, remained intensely attached to de Ruiter, but had trouble reconciling the image of an otherworldly messiah with the less exceptional reality of a cheating husband.

Within weeks, Ms. Parr and a handful of others left the group.

“I miss John,” she told a reporter later. “I miss his teachings on higher consciousness. They are beautiful, but I can’t sweep his behavior, what he’s done to his family, under the carpet.”

For 10 years, de Ruiter divided his time between the von Sass sisters, usually alternating weeks at each of their homes. They worked for him, travelled with him, stood side-by-side with him in evening gowns when the Oasis Centre opened in west Edmonton in 2007.

The Oasis Centre in Edmonton, where de Ruiter holds meetings with his followers.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

Oasis was the headquarters of de Ruiter’s College of Integrated Philosophy, a luxe house of worship built especially to house his meetings, quietly situated amidst warehouses and strip malls in an industrial area a few minutes’ drive from West Edmonton Mall.

A newspaper column at the time of its opening described the building as “something out of Italy, or The Great Gatsby,” with “state of the art everything” and an “upper floor worthy of a New York five star hotel.” On days it wasn’t in use by the group, it was available for public rental as a luxury venue for weddings and events, staffed by a legion of volunteers who did everything from manage daily operations to scrub toilets out of devotion to John.

Among the volunteers was Anina, who moved to Edmonton around the time the Oasis Centre opened. In some ways, she was typical of many of de Ruiter’s followers, a smart and professional woman but driven by a strong desire for spiritual growth and enlightenment. In John, she found not only a leader but a tight-knit community that appeared, at times, almost perfect.

But in August, 2009, de Ruiter abruptly split from the von Sass sisters and legally married another follower, Leigh Ann Angermann.

The sisters then filed lawsuits against de Ruiter and his various corporate entities claiming they were owed significant amounts of money as spouses, employees and benefactors. Oasis has denied these allegations.

The sisters also allege de Ruiter used spiritual pressure, even fear, to manipulate those who believed in him for sex, power and financial gain.

De Ruiter and his wife Leigh Ann, shown in 2014.Facebook

In court documents, Benita, who once described de Ruiter as “goodness and purity personified,” now called him “an opportunist and a huckster.”

“Having been drawn in by the Defendant and initially convinced he was an entirely honest man with deep and great integrity and knowledge, I have come to learn that the Defendant is fraudulent,” one of her affidavits read. “It has taken me years to come to understand this.”

She described de Ruiter fostering “a spiritual obsession and submission to his teachings,” and said he once asked her to imagine killing her children to show her “allegiance to truth,” and used her faith to pressure her into sexual acts.

“The defendant convinced me to sexually submit to him, reminding me that this was ‘God’s will,’” read one affidavit she filed with the court. “The Defendant stated he was the ‘Christ on earth’ and that defying him was to defy truth, goodness and God. Accordingly, I obeyed and submitted.”

She alleged that at the same time de Ruiter was preaching about marital fidelity he was having affairs with married female followers, telling her “his ‘burden from God’ was to act against his own message and to violate his own marriage so as to prepare him inwardly for his upcoming battle with Satan.”

In her own lawsuits, Katrina von Sass portrayed de Ruiter as a persuasive, controlling, and charismatic man who isolated her from her family and, at one point, convinced her to buy a $910,000 house and put it in his name to “contribute to the dearness of their relationship.”

The sisters’ affidavits and the unseemly allegations they contained circulated through the community.

Some, like Anina, pushed the allegations aside or chose not to read them altogether. But for others, the documents ignited serious questions about whether de Ruiter was truly the pure being his followers believed him to be.

Jasun Horsley, who had been on the verge of moving from England to Edmonton to join the community, saw in the affidavits confirmation of doubts he’d previously dismissed as his own lack of faith, a failure to understand an enlightened being operating at a different level than himself.

But inconsistencies had been pulling at Mr. Horsley – like how he heard de Ruiter lived in luxury, though he told followers they must always choose the path of misery and discomfort – and Mr. Horsley wondered whether his teacher was not living the same values he prescribed to others. There seemed to be discrepancies between de Ruiter’s teachings and actions, his public image and private life.

When Mr. Horsley read one of Benita von Sass’s affidavits, something shifted. In that moment, he began to see de Ruiter in a vastly different light.

“I didn’t go from loving John to hating him,” he says now. “But I did go from absolute trust to absolute distrust.”

When Anina moved to Canada to be near de Ruiter, ‘I remember thinking if it made her happier and more balanced, we should just leave it,’ says her sister Johanna Parkinson, shown on a beach in Queensland. Only later, when Anina’s mother and sisters visited her in Edmonton, did she see how her life totally centred on de Ruiter.David Maurice Smith/Oculi

On the day before she disappeared, Anina pulled into the Oasis Centre’s expansive parking lot well after noon, more than two hours late for a morning meeting.

Those waiting for Anina were shocked by her lateness. She had always been organized and meticulous in her work, so dedicated to John that she’d recently asked to work one day less a week at her government job to devote more time to her volunteer work at Oasis. Arriving over two hours late for a meeting was extremely out of character, as was Anina’s seeming nonchalance. Those present would later remember her being pensive and introspective and telling them she was late for a very good or important reason, though she wouldn’t tell them what it was.

In fact, something had been changing about Anina for weeks if not months. Friends would remember her seeming lighter and more animated, sometimes smiling or laughing to herself as though she had a secret she was not yet ready to tell.

She’d lost a noticeable amount of weight, and one woman described her seeming almost elated at times, but then hearing her burst out crying when she thought she was alone. Another recalled her being giddy, smiling and laughing to herself, though she wouldn’t tell him why. Anina told a friend she’d known since childhood that she would never be sad again.

To some who knew Anina, it seemed almost like she was in love.

Her family and friends would have been thrilled if that were so. She was respected and accomplished, a forest entomologist who worked for the Government of Alberta researching pine beetles, but she could be naïve, even innocent, and insecure.

At 32, she was unmarried and still a virgin, and had been extremely uncomfortable even talking about sex since she was a child. Her sisters hoped one day she would find someone who would love her and make her feel as beautiful as she was, and that with love and trust, her discomfort with sexuality and physical intimacy would fade away.

Anina and her father.Family photo; David Maurice Smith/Oculi

Top: Anina and her father. Bottom: Anina lies between her sisters Johanna and Anna.FAmily photos; David Maurice Smith/Oculi

Anina was German but had grown up in South Africa, the youngest of three girls, whose family nickname translated to “little hoppity” because she skipped everywhere. But she could be dark and emotional, too, with outbursts that left her family reeling.

She first fell under the influence of a spiritual leader working at a non-profit in India after high school, and returned home almost unrecognizable: extremely thin and dressed in traditional Indian clothing, telling her family they should be eating on the floor and no longer touching dogs; upset about lawn-mowing because of the violence inflicted against the blades of grass.

Her family played along, thinking the phase would pass, and it did. But while attending university in England in the early 2000s Anina got involved with Andrew Cohen, a controversial American spiritual leader later accused of being abusive and controlling. That too passed, and Anina extricated herself from the group amidst bullying and threats from other followers.

But in those experiences, Anina glimpsed what she believed to be enlightenment, and she told her mother she would dedicate the rest of her life to finding truth. Sometime around 2006, she went to a John de Ruiter meeting in England. By the time she finished university, she was ready to move to Canada to be near him.

“She said, ‘Oh no, it’s completely different.’ And, at first it sounded that way,” recalls her older sister, Johanna Parkinson. “What we sort of grasped was truth and beauty, it’s all about truth and beauty. She seemed happier for it, and more balanced. I remember thinking if it made her happier and more balanced, we should just leave it.”

Visiting Edmonton in 2008, Anina’s mother and sisters began to glimpse the full extent of de Ruiter’s influence. Outside work, Anina’s life was almost totally focused around de Ruiter and the group, and he was involved in all aspects of her life.

It was disturbing, but by then Anina’s family had been in contact with sect specialists in Germany who warned any kind of confrontation would only increase the divide. They told Anina’s mother and sisters to focus on things they had in common, to hold on to the bonds of family and shared experience. But still they saw the distance growing between them. When Johanna asked why de Ruiter sometimes just stared silently at those who asked him questions, Anina said, “He’s giving an answer on a different sphere, and you can’t see or hear that because you’re not enlightened. You’re not part of it.”

On Saturday, March 22, 2014, Anina went to her office in downtown Edmonton. Though not scheduled to work, she stayed much of the day, leaving only briefly to meet a tenant in a townhouse she owned, another follower of de Ruiter’s, who signed a new lease and gave her post-dated cheques for rent. Her last phone call was to talk about volunteer scheduling at the Oasis Centre.

When Anina didn’t show up at the party with John that night, and when she wasn’t home the next day – and uncharacteristically missed both of the group’s Sunday meetings with de Ruiter – her roommate began to get concerned. A member of the group who spoke German called Anina’s mother to tell her family she was missing.

At first, Johanna wondered if maybe her sister had finally grown disillusioned with John de Ruiter, as she had with Andrew Cohen, and had found it necessary to disappear as a way to leave. Through a mixture of hope and belief, she imagined Anina showing up at her mother’s door in Germany, safe and free.

But Anina’s passport was at her apartment with the rest of her possessions, and her car was found three days later parked on an isolated Alberta highway.

A box of the belongings Anina left behind at her apartment before her disappearance, including her Alberta driver’s licence and health card.

A page from Anina’s diary. Some journals appear to refer to sexual encounters between her and de Ruiter, though a law firm representing him denied this, telling the family that these were 'visions.'

Anina’s disappearance was as mysterious as it was disturbing. She’d recently requested vacation time at work and had flights booked to Germany and Australia to visit her family. Though she enjoyed the outdoors and sometimes worked in the wilderness, there would have been no reason for her to be alone in a remote area on a dark and frigid Saturday night, certainly not without her coat, wallet and phone.

Police officers investigating Anina’s disappearance talked to her family and friends and examined diary entries written in English and German, looking for any clue about what may have happened, any talk about threats or suicide.

Among the entries in early March, investigators found what appeared to be references to sexual encounters between Anina and her spiritual leader, John de Ruiter.

“The next day I tried to make sense of why he moved that way with me. I was wondering what the consequences would be, whether he is doing this with everyone…,” one entry read. “I knew more deeply that all there is for me to do is to respond and keep opening, no matter what the consequences are. I wondered how John can make love with many women while being married to one. What he is can’t be contained, it can’t be owned. When I go into my mind and emotions about it I get confused.”

Another passage read, “You don’t understand why he did that. Don’t draw any conclusion in yourself about that experience. It would be safe to treat it as an awakening that you might understand later. For now don’t assume it will continue, don’t make anything up that you can have from it. Take care that you have a clean mind and don’t push the experience to have more.”

Her body was found seven weeks later near Nordegg, where the group went for summer camping trips and where de Ruiter sometimes held survival training or “hell proofing” for the dark times he predicted were coming. She was twelve kilometres away from where her car had been found, a tough slog over difficult winter terrain. Her remains were too deteriorated for an autopsy, but there were no indications of violence or foul play. The police investigation was closed as “non-criminal,” which can be used to describe either an accidental death or a suicide, and means police didn’t find any evidence to indicate a crime occurred.

In the spring of 2015, around the first anniversary of her death, Anina’s family decided to make excerpts of her journals public. It was a difficult decision. Anina had been intensely, almost pathologically, uncomfortable about sex, and her mother and sisters struggled with sharing her private writings. But they knew she had been a virgin not long before she died, and reading diary entries that appeared to describe her having sex with de Ruiter was stunning.

“To us, we read it and thought, ‘Well, this is the answer,’” Johanna says. “If that’s what he did to her, no wonder she went to lie in the snow to die.”

The family didn’t know if that was the case. Spiritual or “energetic experiences,” including sexual ones, were not uncommon in the group and the writing in the diary was abstract and unclear – far from proof anything physical had happened between Anina and de Ruiter. Interviewed by police after her disappearance, de Ruiter had firmly denied any kind of sexual relationship.

But whether something physical had transpired between them or not, Anina’s family felt like de Ruiter held Anina’s life in his hands, and that he had failed her.

In one of her last diary entries, Anina wrote that if one could prevent suffering it was their responsibility to do so, and that line pushed her family forward. They thought the rest of his followers deserved to at least know what she had written, and could decide for themselves what to make of it. If it had happened with Anina, her family believed she would not have been the only one.

“We, Anina’s sisters and mother, feel we need to share something with you that we have thus far withheld…,” their statement began. “The more we have thought about it, the more urgently we now feel the need and moral obligation to entrust you with what we believe is the true reason that she left us. Because it concerns all of you at least as much as it does us.”

Their letter spread in e-mails and on a website. Someone in Edmonton printed it out and distributed it during a meeting, tucking crisp pages under windshield wipers in the long rows of vehicles parked outside Oasis, while inside, de Ruiter and his followers sat in silent connection.

Within days, Anina’s family received a letter from a law firm representing de Ruiter threatening legal action. The letter said de Ruiter did not have any kind of sexual relationship with Anina, but that Anina told her roommate de Ruiter would come to her “in some sort of vision, teaching her about deeper levels and the nature of sexuality.”

“These ‘visions’ appear to account for the comments in Anina’s diary,” the lawyer’s letter read.

It also took issue with the family’s description of a phone call between de Ruiter and Anina’s mother, and said the family had created “a misleading portrait of Anina, which diminishes her memory.”

“She was intelligent, thoughtful and independent, rather than the weak person depicted in the letter,” the lawyer’s letter read. It said de Ruiter reserved the right to commence legal proceedings against her family. A message about Anina was also posted on the College of Integrated Philosophy website, again asserting her diary entries described “nothing other than waking dreams and visions.”

“Out of respect for Anina’s memory, and the others affected, everyone is encouraged to ignore this false speculation,” it said. “The truth is consistent with what we always knew about Anina.”

Over the years, cassettes, videotapes, pamphlets and public meetings helped John de Ruiter to recruit more followers, some of whom moved to Edmonton to be near him.

De Ruiter’s followers sometimes weep when they feel his gaze, while he stays uncannily still for hours at a time.

To those who believe in him, John de Ruiter is an innocent and humble teacher, unconcerned with the empire of worship that has grown around him. But he is also a businessman heading an extremely profitable, multi-million dollar enterprise, fiercely protective of both his image and interests.

In addition to threatening legal action against Anina’s family, de Ruiter has threatened lawsuits against journalists writing about him, and sued his ex-wife Joyce and former followers for videotapes, photos and possessions. Joyce previously told reporters their divorce documents included a clause preventing her from saying or doing anything that would hinder his earning potential.

In her 2009 affidavit, Benita von Sass estimated de Ruiter’s personal assets at nearly $9-million, including his equity in the Oasis Centre, a $75,000 monster truck, the home purchased by Katrina and put in his name, and personal income estimated at $232,000 a year. That estimate may now be significantly higher.

Attendees pay $10 to attend a meeting with de Ruiter, and while that may seem a token amount for individuals (“It costs that much to go to a swimming pool,” one person told me), with 350 people or more attending four times a week, meetings alone could bring in over $56,000 a month.

There’s also revenue from de Ruiter’s books and downloads (the full collection costs about $3,000), and income from the Jewel Café, where followers are encouraged to gather for “Hot food, snacks, delicious treats and barista-made espresso drinks” before meetings. Special events, retreats and seminars all cost extra and draw hundreds of participants. Full registration for the upcoming winter seminar with de Ruiter in Edmonton is $870 a person. The Oasis Centre can charge $13,000 for a single day of public rental.

Some people also give donations directly to de Ruiter or Oasis. (One woman described giving him $300 a month in the late 1990s, and in her affidavit, Katrina Von Sass said she once remortgaged her home and gave him $60,000.) Others estimate their involvement cost thousands of dollars a year, on top of their volunteer labour.

At 58, de Ruiter has several hundred devoted followers in Edmonton, and hundreds, maybe thousands, more around the world. But the effect is strongest in person, which is why people travel to be near him, why they move to Edmonton just to be close.

One woman likens being with de Ruiter to “powerful bursts of energy,” and said whenever she began to have doubts, being with him made her believe again.

“He starts talking about you and your consciousness and it’s so beautiful, and in the moment you feel powerful. You feel that what he’s saying is true,” said the woman.

“And, ‘the connection with the beloved and the universe and the stars’ and ‘what’s important is your awakening because here is the place you have to be.’ And you fall again. It’s crazy but it happens.”

From a leather chair on a stage custom-built for his veneration, de Ruiter scans the crowd, his eyes pausing for seconds or minutes before moving on again. Large screens flanking the stage show his face expanded in crisp focus, clear blue eyes glistening as his gaze moves through the crowd.

Through the years, his manner during meetings has developed and deepened.

Where he once sat casually and gestured as he spoke, he now stays uncannily still for hours at a time, the only movement the blinking of his eyes, the soft changes to his face as he talks.

When he speaks, it is in a slow, stuttering voice. He pauses frequently, and often falls silent for long periods. His website describes him as both a philosopher and a spiritual pioneer, and promises followers “the realization of meaning in all aspects of our existence” through “core-splitting honesty.” His words are, depending on your perspective, extremely profound or totally meaningless.

“Being open means that your gates are open,” he says.

He says, “What is next isn’t for everyone. What is next is for openness in anyone.”

His followers, when they feel his gaze, sometimes weep. They have visions and hallucinations, feelings so profound one former follower likened the effect to “a drunken honeybee.” Others call it “John-gone,” blissed out on de Ruiter and the portal he provides to greater truths, part of what they believe is the next evolution of human consciousness.

In this intense and intimate environment, it is not unusual for both male and female followers to believe they’re in love with de Ruiter. Multiple people told The Globe and Mail about their own strong, and sometimes confusing, feelings toward him, or shared stories of others who fell in love with him or believed they would become one of his wives.

“I almost lost my life because I was so bad in my mind that I was out of it,” said one woman, who told The Globe and Mail her attraction to de Ruiter led her to the point of a breakdown, though there was never a physical relationship between them. “I was very, very confused, and I came to John and he was harsh,” she said. “The few times I spoke to him in order to find clarity he was harsh and rude and hard.”

The parent of another follower described their daughter giving herself to de Ruiter “to the point of self-abandonment.”

“[My daughter] says that John is the most important person in her life and that everything and everyone comes second…,” said the parent, who asked not to be identified because of concerns of further fracturing the remaining family relationship. “And there is reason to believe that she is in love with him, not physically, but she adores him like young naive girls adore a man that [they] cannot have.”

Stories of sexual relationships between de Ruiter and his followers have quietly persisted within the community for years, but came to the forefront in late January when a woman from Denmark posted a statement inside a closed Facebook group describing being approached for sex by de Ruiter at his house last fall.

The woman said de Ruiter’s wife was beside him as he said, “For some years now, the calling has moved me to be with other women sexually and now the calling is moving towards you.”

The woman wrote that after consideration she declined the offer. Not because she was necessarily opposed to the idea, but because something seemed out of “alignment” with the situation, including that it was not being discussed openly within the group and that de Ruiter – “the living embodiment of truth” – repeatedly asked her not to tell anyone. She recalled him saying, “The world is not ready for this. People will not understand. I will seem like a cliché.”

“Several spiritual teachers and even masters have done this. Some openly, others behind the curtain. No surprise here,” the woman wrote. “It has to be said though that I really hope that each and every woman John has approached in the way he approached me is equally fairly mentally and psychologically sound as myself. Otherwise, this Calling of John’s would suggest a power abuse and then the whole issue is taking on very different dimensions.”

After the post, a second woman came forward within the community with allegations of unwanted sexual advances by de Ruiter, and said she, too, had been told to keep it secret.

In an e-mail shared with members of the group, the woman told de Ruiter she was torn between what he was telling her to do, and what she felt was right.

“Living in this split of having to choose between what my natural movement is and what you are telling me to do is leaving me unhappy and confused,” she wrote to him. “I love you and when you clearly stand against what I am saying, I follow you but it leaves me in a very dark place.”

She wrote that she stopped doing her “homework” because, “it was damaging imposing sexuality on what was innocent.”

Questioned by another person on what that homework was, the woman responded, “it is too much for me to say in a public arena.”

Within weeks, de Ruiter’s son, Nicolas, posted a lengthy blog post in which he talked about his father’s sexual relationships with married women in the community, and said he had been given the names of the women, “to create a third party for accountability and support.”

Nicolas recalled his father describing to him a “knowing,” as powerful as his original teenage enlightenment, that he would “be with a number of women in sexual relations with a purpose of meaning, truth, and the realms he opens in meetings.”

Nicolas wrote that he struggled with the idea, but ultimately concluded his father’s conduct “is true and beautiful.”

“Could I say that John would dismiss his family, his following, his personal values for sex? No way,” he wrote. “It is easy to generalize about male sexual appetite, but I believe that a true man would be taxed and not enticed by sex with multiple women.”

He wrote, “I chose my direct experience of John as the higher standard of truth.”

The group’s “Accountability Committee” – originally formed in the wake of Katrina and Benita von Sass’s lawsuits – also sent out an e-mail acknowledging “some deep considerations, that are troubling to many.” It said the committee spoke for many meetings about “the movement of the calling through sexuality” but that, “Through John’s opening this up in a deep, delicate, sensitive, discreet and forthcoming manner” the committee was able to reach “new understandings” and “a depth of restedness.”

“The members of the Committee have seen that what comes from John has always been good,” the e-mail read, “and we continue to meet every month or two, looking at what is moving in the community and how we can all take care in the best way possible. "

It was signed by eight people, including John de Ruiter, his son Nicolas, and his wife Leigh Ann.

But for some, this new openness around de Ruiter’s sexual relationship may have come too late. While members of the group may not be opposed to the idea in theory, secretive sexual relationships are clearly contrary to de Ruiter’s teachings of “core-splitting honesty,” and there is potential for the relationships to be confusing – even dangerous – for those who look up to him as an advanced spiritual being, or even believe he is a god.

And revelations of sexual relationships with other women have revived lingering questions about the events that led up to Anina’s death. If de Ruiter was secretly having sex with other female followers, could he have done it with Anina as well?

What if the living embodiment of truth was lying?

“It takes only one word to destroy their beloved reality. ‘Anina’,” one observer wrote on Facebook. “Cause deep, deep down they all know the truth.”

Johanna Parkinson holds an old photo of herself with Anina, her youngest sister.David Maurice Smith/Oculi

In a group where questioning de Ruiter can be both subtly and openly discouraged, “the disclosures,” as they are being called, have sparked unprecedented dissent. Some who have been with de Ruiter for years – even decades – are leaving the group, even calling publicly for de Ruiter to be confronted or exposed.

Discord has continued to simmer on chat boards and in private groups, in discussion threads with titles like “John de Ruiter Disclosures: What Do They Reveal?” and in documents and screengrabs circulated in e-mails and private Facebook messages. There have been inflammatory allegations to Birds of Being, the private Google group for followers, and some who devoted much of their lives to de Ruiter have moved to a new page, Home, for those who have left.

But De Ruiter’s personal pull is strong, the community he has created a powerful glue. He has been questioned before – after his breakup with Joyce, with Katrina and Benita, then Anina – and has always survived. His reach expanding, his influence growing stronger.

The University of Alberta sociologist Dr. Kent, who has now been watching the group for two decades, says a sense that the outside world is against de Ruiter could even be used to de Ruiter’s advantage, and he could see de Ruiter expanding international operations or embarking on a big new project as a way to bring people back together.

Dr. Kent says an increase in talk about the apocalypse, which some former followers have reported to him, could be a way to draw the community closer and shut out any questions and doubts, which many followers will be happy to do. It is far harder to leave than to stay. “The more you invest in something the harder it is to walk away from it. It is very hard to leave,” Dr. Kent says. “The consequences for the people who have devoted themselves to him and thought he was beyond human can be devastating.”

Dr. Stephen Kent suggests that, if de Ruiter's supporters believe the outside world is turning against him, he could use this to his advantage.Jana G. Pruden/The Globe and Mail

That belief is powerful enough that some who have lost faith in de Ruiter remain unwilling to discount his abilities, seeing him as an extraordinary being who has become corrupted, rather than an ordinary human with a lucrative act.

Multiple people contacted by The Globe and Mail said they were afraid to speak publicly against de Ruiter out of fear of “psychic violence” or bad energy being directed at them, and some said they have personally experienced the effects of such attacks in the past.

Others said they were afraid of retribution from others in the group, or of being judged by those on the outside for their involvement.

“People give John a lot of powers, and he may or may not have any. I’m not sure,” said one woman, who said she believes she was targeted when she left the group.

“I think he probably believes he is someone very, very special. I’m not sure if that’s part of the game, part of what he’s playing or if he believes it. That’s the million dollar question with John, is where he is actually in all of this.”

Stories circulate that de Ruiter studied hypnotism for two years, and in past interviews, de Ruiter’s ex-wife, Joyce, described him spending nearly a year studying with a new age practitioner in the early 1990s, then coming home in the evenings and staring at Joyce and their children until they saw visions.

Scientific studies have shown that concentrated staring can have profound effects, and staring is a well-documented method of both persuasion and seduction – capable of inducing significant changes in perception, a sense of being detached from the world or in a dream, and feelings of being in love.

A 2015 study found 90 per cent of subjects began hallucinating after staring into another person’s face in a dimly-lit room for 10 minutes, seeing other faces, spiritual forms or monsters, like some of de Ruiter’s followers describe.

Stanford University hypnotism expert Dr. David Spiegel says there is also clearly a “hypnotic-like potential” at de Ruiter’s meetings, which could evoke the powerful responses some people experience.

Dr. Spiegel says he was personally able to replicate a profound religious experience in a patient through hypnosis. “And believe me, I’m not Jesus,” he added. “You can interpret an unexpected ability to change the way your body feels as a sign of some great religious significance, or not.”

Other former followers attribute de Ruiter’s power to the dynamic of the group itself, that, in essence, the group is creating him with the strength of its belief.

A spokesperson for de Ruiter declined The Globe and Mail’s requests for an interview, writing, “After careful consideration of your request, we are not sure if this feature is quite the opportunity that we are looking for at this time.”

‘I honestly see the best thing for John is for this to come apart,’ Joyce de Ruiter Kremers says.

From her home in Holland, Joyce de Ruiter Kremers has been watching, waiting for others to understand what she saw clearly nearly two decades ago. That her ex-husband is not a god but a man, and that what has grown up around him is not right.

“Nobody would believe it, but I do care. I really do care about John,” says Ms. de Ruiter Kremers, who declined to do a full interview because of what she describes as the “delicate situation” with her children, two of whom are followers of their father.

“I honestly see the best thing for John is for this to come apart. Somewhere there is just a normal guy who should be living just a normal life, who is loaded with qualities and I think was once a guy with integrity… I think that the best thing we can do is to help to pull the curtain back. I actually think that would be good for John. Very detrimental, of course, but ultimately good for him.”

She says she hopes his followers will at least be willing to listen to their doubts, no matter how difficult it is. “To be willing to consider, even though your world will fall apart, that everything you wanted to believe for however long may not be so.”

Her words echoed the final line in Anina’s diary, the last words a lonely woman wrote before disappearing into a dark Alberta night: The idea that when you know the truth, you must face it, regardless of the cost.

On a Sunday afternoon, inside a grand building in west Edmonton, John de Ruiter sits silently under a beam of light, gazing out at a room full of his followers. Hundreds of people, eyes searching, each waiting for the moment he stares back.

Jana G. Pruden

Jana G. Pruden