David Peterson knows minority governments. He was witness to Tory premier Bill Davis's management of a pair in Ontario in the 1970s, and he himself became premier of that province in a minority.

But Mr. Peterson is incredulous at the current situation in British Columbia, where voters elected a minority government for the first time in six decades – one that Mr. Peterson notes is the rarest of a rare breed.

"I don't think there's a guidebook on this. I don't think there's a template," Mr. Peterson said in an interview this week.

He was referring to making minority government work. In 1985, Mr. Peterson's solution was a model some in British Columbia have referenced.

There have been 13 minority governments at the federal level, most recently Stephen Harper's five years of minority governance that ended with the 2011 election in which his Conservatives won a majority. And there have been at least 28 in Canada's provinces and territories since 1867. The last time British Columbia had one was in 1952 and it fell the next year.

And while they may seem precarious to a public gripped with news about the government's potential fall at every critical vote, they can offer stable stewardship with significant achievements, political scientists say.

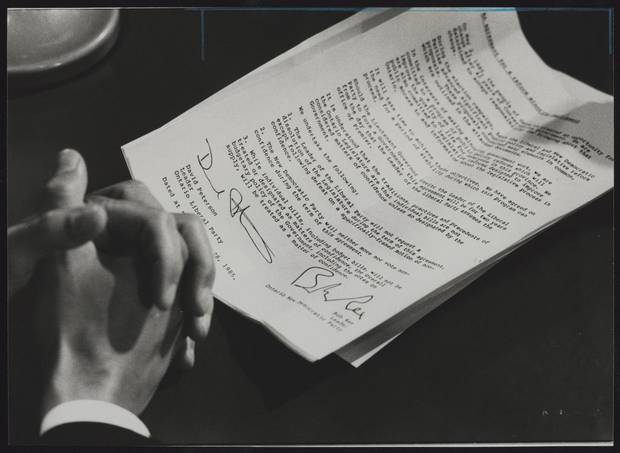

After the Ontario Tories came up short in the 1985 election, Mr. Peterson's Liberals signed a deal with Bob Rae's New Democrats that saw the NDP back the Liberals for two years of minority government, enacting an agreed-upon program. The Tories had 52 of the legislature's 125 seats, but the Liberals had 48 seats and the NDP 25. After striking the deal, the Liberals and New Democrats voted out the Tories in a series of confidence votes, about a month after the provincial election, ending nearly 42 years of Progressive Conservative government.

Ontario's lieutenant-governor of the time had made it clear to Tory premier Frank Miller that he would not trigger an election should Mr. Miller lose a confidence vote. Mr. Miller resigned after the defeat, leaving the way clear for Mr. Peterson to become premier with the support of the NDP.

But Mr. Peterson doubts there is much in his experience that's relevant to British Columbia after this month's election.

For one thing, he says, the Ontario NDP had 25 seats compared with three for the Greens, now holding the balance of power in British Columbia.

He said he's skeptical about hinging a government on so few Green seats. Both the BC New Democrats and the provincial Liberals are trying to win over Green support in ongoing negotiations.

"I am telling you it's a recipe for mayhem," Mr. Peterson says of the current B.C. scenario.

"It's all about the numbers, and I don't see an easy answer here. If it was one or two more, one way or another, it would be easier.

"This is the most fragile of fragile governments."

Political scientist Cristine de Clercy has been monitoring the province. Her mother lives in the riding of Courtenay-Comox, which was under a microscope as final voting numbers there were seen as pivotal to governance in B.C., one way or another. Ms. de Clercy was also living in Saskatchewan in the 1990s when that province had an unusual run of coalition government.

"There's a lot of speculation that the [provincial election] results will herald a period of deep uncertainty in British Columbia and it's true that minority governments are thought to be somewhat less stable than majority governments, but they are part and parcel of the sort of system we have had," said Ms. de Clercy, who specializes in Canadian politics at the University of Western Ontario.

"In Canada, most minority governments have been very productive. They have produced good legislation that satisfied at least some of the public. They have pretty much functioned as they should, which is to provide a stable period for the exercise of authority."

Lester Pearson's 1960s-era federal minority governments produced such milestone programs as the Canada Pension Plan.

The Ontario Liberal-NDP initiative led to action on an agenda that included extra billing by doctors, extended rent controls, French-language government services as well as broadened provisions of the Ontario Human Rights Code. Once the two-year deal expired, the Liberals won 95 out of 130 legislature seats in a 1987 election. The NDP won a majority in the subsequent election.

But Mr.Peterson says it can be a precarious situation.

"You've got to always think about commanding that support in the House and so you have to be very sensitive to all the noises and everything around you, and you can't overplay your hand," he said. "You think, 'Supposing this doesn't work and we have to go back to the people. Who would win?' " He said he was always confident his Liberals would have won an election had that been necessary.

In 1999, Saskatchewan New Democrat Roy Romanow watched as his NDP was reduced to a minority government in the provincial election. The NDP had 29 of 58 seats against 25 for the Saskatchewan Party and four for the provincial Liberals.

"My first reaction was perhaps in the best interests of the province, to begin with, and then the party as well, I should step down," Mr,. Romanow said in an interview this week from his office at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon where, among other things, he is writing memoirs that will cover what followed that moment of decision "I felt it was a non-confidence vote," Mr. Romanow said, adding quickly, "I am not saying that applies to Premier [Christy] Clark."

"My next consideration was a question of whether or not we could give some stability and move what I viewed to be a progressive agenda forward by working with the Liberals."

But Mr. Romanow, who had already been premier for a dozen years, had a caveat: He felt it would be necessary to bring Liberals into cabinet for a properly functioning government given the need for the NDP's new partners to understand governance.

"It was for stability purposes. There's no doubt about it. That was a big factor," he said.

"You want to have stability with respect to the articulation and implementation of government policy to which the minority government, coalition or otherwise, will take credit or blame if the particular policy or policies don't work."

Asked if he is offering that point as advice to B.C, Mr. Romanow says," It's an observation based on practical experience."

He said B.C. New Democrats have not sought his advice.

In Saskatchewan, two Liberals were appointed to cabinet and a third appointed Speaker.

Gregory Marchildon was deputy minister to Mr. Romanow and cabinet secretary at the time, and did research on coalition governments around the world to help facilitate the arrangement.

In an interview this week, Mr. Marchildon, who has since written extensively on coalitions as an academic, says minority governments and coalitions exist on a political continuum. Coalitions, he said, come out of minority government.

Speaking to B.C., he said, "There is a minority government. To have stable government in a parliamentary sense, you have to have a coalition or a very tight agreement falling short of a coalition."

The current professor and Ontario research chair in health policy and system design said the ongoing talks among parties in B.C. probably reflects one key point. "The reason they're negotiating is they already have a preference for a more stable situation than the highly precarious situation of a minority government."

Mr. Romanow left politics in 2001, but the NDP went on under new leader Lorne Calvert, regaining a majority. The Liberals were wiped out. Mr. Romanow, reflecting now, says the party "paid a price" among its own supporters for working in the coalition with the NDP.

Mr. Marchildon says this will be a risk for the B.C. Green Party, as well, forcing it to cautiously decide how it exercises its influence, and then sell the idea to its base.

"They have got to make sure, probably, that their grassroots are OK with it. You have got to have the party activists on side."

He also recommended that all parties must release any agreement as soon as its concluded.

Some level of trust is also key in minority governments among party leaders, he said. "They don't have to like each other, but they have to trust each other."

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL: