Canadian author Madeleine Thien was feted on two continents this week – in Canada as the winner of the Governor General's Literary Award for Fiction and in Britain as a finalist for the prestigious Man Booker Prize. Her novel, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, is also shortlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Quebec Writers' Federation's Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction and longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. But it's something else written by Ms. Thien that has Canlit circles quietly abuzz as authors travel from one literary festival to another this fall.

Late last month, she sent a letter to the University of British Columbia, instructing her alma mater that her name be removed from all UBC web pages, alumni publications and social-media feeds. She says she no longer wants to be associated with the university as a result of its handling of the controversial case against her friend, Steven Galloway, an internationally renowned author who after a months-long investigation was fired from his position as chair of UBC's creative writing program.

"The university has taken a tragedy and turned it into [an] ugly, blame-filled, toxic mess, destroying lives in the process," she writes in a five-page letter that calmly berates UBC. She suggests the university has inflicted terrible damage on Mr. Galloway by terminating him, stigmatizing him and making him the target of a whisper campaign, and accuses UBC of doing so in order to safeguard its reputation.

To protest against its handling of the case, Madeleine Thien, a UBC grad who this week won the Governor-General’s Award for Fiction, has written asking that her alma mater remove her name from its website and publications.

Read her full letter here.

CHRISTINNE MUSCHI FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Mr. Galloway, now 41, is the author of four published books including the bestselling, award-winning novel The Cellist of Sarajevo and, more recently, The Confabulist. He became a tenured associate professor in the creative writing program and acting chair in July, 2013; officially becoming chair two years later. In numerous interviews for this story, he has been described variously as charismatic, popular, funny, warm and caring – as well as manipulative and hot-tempered with the potential to be nasty and vindictive.

Last November, the university announced that Mr. Galloway had been suspended with pay due to "serious allegations." It appointed retired B.C. Supreme Court judge Mary Ellen Boyd to conduct an independent investigation and, in June, fired Mr. Galloway due to "irreparable breach of … trust."

The investigation, allegations and report findings have fallen behind a curtain of non-disclosure and privacy. The accusations, never made public by the university, included sexual assault, sexual harassment and other inappropriate behaviour such as bullying. They have been dealt with by the university – not the police, not the courts.

The scandal – with gaping holes in official information and the resulting speculation and innuendo – has devastated the vaunted writing program, which was established more than 50 years ago by Canadian poet Earle Birney and whose graduates include award-winning authors Lynn Coady, Charlotte Gill and Lee Henderson, as well as Ms. Thien. It has also inflamed Canada's tight-knit literary community and irrevocably altered many lives. Mr. Galloway, who was never charged with a crime, lost not just his job, but his reputation – and all that implies for his publishing career.

If this is a test case for how institutions handle serious allegations – treating complaints with the gravity they require while also offering due process to the accused, all in an extra-judicial environment – there are people on every side of the investigation who would give UBC a failing grade: some alumni, Mr. Galloway himself, some of his former colleagues and, even if they're pleased with the decision, the complainants themselves.

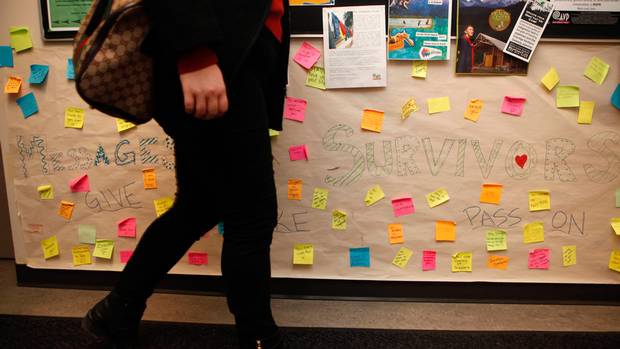

Life changed for writers and course graduates Chelsea Rooney, left, and Sierra Skye Gemma, right, after they came forward to volunteer their testimony in the case.

RAFAL GERSZAK FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The 44 pages – more than half of them redacted – felt like yet another slap in the face for Chelsea Rooney and Sierra Skye Gemma when Ms. Boyd's report arrived in their respective inboxes last month.

For nearly a year, the two women have been embroiled in the Galloway investigation. Distraught over what they've experienced, the complainants – both graduates of the program – have come forward to voice their concerns with the system, their treatment by UBC and their disappointment with what they believe was in Ms. Boyd's final report – which, to obtain, the women had to submit requests under freedom-of-information legislation.

They say they have felt misled, mistreated, kept in the dark and silenced by the university. They cite concerns about breach of confidentiality and say they were given inconsistent information. And they were shocked – even "disgusted" – at what they understood was missing from the final report; they feel their complaints were not accurately reflected.

The Globe and Mail met with the two women at length and has seen their copies of the report, which have been redacted (information about other complainants and witnesses edited out to protect confidentiality), as well as correspondence between them and the university. Because their copies are so heavily censored, The Globe has not seen the parts of the report that deal with the sexual-assault allegation at the heart of the scandal. The woman who made that allegation has declined to be interviewed.

Ms. Rooney and Ms. Gemma came forward initially as witnesses in support of that woman, the main complainant in the case. "MC," as she is called in the report, confided in them, separately, with her allegations about Mr. Galloway, they say. Both had concerns of their own about Mr. Galloway – not sexual assault, but other allegations ranging from sexual harassment to bullying to playing favourites.

Ms. Rooney, 32, joined UBC's creative writing program as an undergraduate in 2005 and entered the master of fine arts (MFA) program in 2008. She graduated in 2012. Her debut novel, Pedal, was published in 2014 and was a finalist for the Amazon First Novel Award and the ReLit Award for books from independent publishers.

Ms. Gemma, 38, attended the MFA program from 2011 until 2015; her graduation ceremony was last November, "mere days after this bomb dropped," she says. She is an award-winning non-fiction writer who has been published by The Globe and Mail and others. She was employed by the creative writing program in an administrative role, financial processing specialist, when Mr. Galloway was suspended.

The women fear their rocky experiences throughout this process could deter others from reporting inappropriate behaviour on university campuses – or beyond.

"I have seen, heard and experienced things I never thought possible for an enlightened institution," Ms. Gemma wrote in a letter to UBC. "Isn't the university supposed to be a place for ethical, critical, and progressive thought?"

RAFAL GERSZAK FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The inquiry into Mr. Galloway was triggered last November after the woman at the centre of the sexual-assault allegation – MC – circulated a letter written by UBC alumna Glynnis Kirchmeier about the troubling way the university had handled allegations of sexual assault and harassment against a graduate student in its history department (which, like creative writing, is in the faculty of arts). This was to be the subject of an upcoming episode of CBC's The Fifth Estate which was causing quite a stir on campus. MC was an MFA student in the creative writing program and the letter she had forwarded was brought to Mr. Galloway's attention as program chair. In a panic, he called the woman – with whom he had had extra-marital relations in the past, while she was a student in the program, according to several sources.

"I would like to, number one, have a chance … to apologize to you and, number two, just assure you that I will take responsibility for our relationship," Mr. Galloway said in one of two voicemail messages he left for her, worried she was going to reveal information unrelated to the history department case – about himself – to creative-writing professor Keith Maillard, a recipient of that forwarded letter and someone with whom Mr. Galloway had been very close. "I think actually what I'm asking for is maybe a chance, if you wish it, for me to turn myself in. As I think you know, Keith's opinion of me matters a great deal to me, and I'm pretty ashamed of the way I used to be and act. I can assure you that I am no longer that way," he said.

In that message, Mr. Galloway referenced equity training he had undergone and said he had turned over a new leaf and was trying to be a better person. (Prof. Maillard declined The Globe's interview request.)

UBC is developing a new sexual-assault policy, as now required by the province.

Under current policy, a professor must declare to his or her supervisor any sexual relationship with a student to determine how to manage the conflict of interest. "There is an inherent power imbalance between faculty and students," UBC's managing director of public affairs, Susan Danard, wrote to The Globe in response to a list of questions about the case. "Faculty members must avoid or declare all conflicts of interest, including those that involve relationships with their students. … If this policy is violated, a faculty member may face disciplinary measures."

Soon after Mr. Galloway left his messages, the woman sent an e-mail with allegations about him to Martha Piper, who had been appointed UBC's interim president after the resignation of Arvind Gupta the previous summer. The complaint went beyond an affair.

At MC's suggestion, a faculty member approached Ms. Rooney, who shared her own negative experiences regarding Mr. Galloway and said she believed there were others with concerns about him.

That weekend members of the creative writing faculty were summoned to an extraordinary meeting at the home of Linda Svendsen, a colleague who a few days later became acting co-chair with Annabel Lyon, another faculty member at that meeting. The allegations were revealed to those in attendance and a discussion followed. It was suggested that there were additional complainants.

The sharing of this information was remarkable for a university that has been so careful to emphasize the legal requirements around confidentiality in this case. "UBC has a legal obligation to protect the personal information of individuals under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act," Ms. Danard wrote to The Globe, explaining why many of its questions could not be answered. "All employers are restricted from talking about the reasons why someone resigned or was terminated." (Ms. Danard has emphasized that UBC has no inherent interest in limiting disclosure about this case and would be more forthcoming, should Mr. Galloway and the related complainants consent.)

Mr. Galloway was in the United States for a speaking engagement when he learned that he was at "the center of a sexual-assault investigation between him and one of his students," according to an incident report filed by police in Fairborn, near Dayton, Ohio. Officers had been called to Mr. Galloway's hotel, the report stated, by colleagues worried that he might be suicidal.

"He explained that he has never felt this low in his life, and is very upset at these false allegations as they are likely to lead to him losing his job," the report states.

Mr. Galloway was taken to hospital by police and "committed against his will," Ms. Thien reveals in her letter to UBC. She writes that the incident was so traumatic for Mr. Galloway, it prevented him from seeking help later when he truly needed it.

In Vancouver, he was suspended with pay, and an announcement to that effect was made by dean of arts Gage Averill. It said Mr. Galloway had been suspended due to "serious allegations." It did not specify the allegations and stressed that there had been no finding of wrongdoing, adding that the university's priority was the "safety, health and wellbeing of all members of our community." It also noted that counselling was available.

This week, in response to a query from The Globe about why UBC publicly released Mr. Galloway's name, Ms. Danard wrote that it was because he "was in a leadership position and it was therefore necessary to advise of his absence as chair."

There was a shocked, even panicked atmosphere at the program. But instead of university officials contacting other would-be complainants, Ms. Rooney – an alumna – was tasked to do it, given a memo to hand out to others she believed had complaints.

"You are receiving this letter from me because the person delivering it to you thinks you may have a complaint against Professor Steven Galloway," began the memo from Sara-Jane Finlay, the university's associate vice-president of equity and inclusion. The memo promised "confidentiality will be maintained as much as possible." And it concluded: "We understand how challenging this may be for you to come forward. We honour your strength and will do our utmost to support you in this process."

Meanwhile, Ms. Gemma says she was asked to look up "a bunch" of requisitions that involved Mr. Galloway. "I believe that UBC was very thoroughly investigating all his actions as chair of the program," she says. The program was now under a microscope – Mr. Galloway's actions in particular. Had spending, hiring and the decisions behind student awards been handled properly? (One of the relevant sections UBC cited in its conflict-of-interest policy covers situations in which a "UBC person" is in a position to influence human-resource decisions including recruitment, offers of employment or admission decisions with respect to a person with whom he or she has had a relationship.)

Ms. Gemma and Ms. Rooney came forward initially as witnesses, to relay what they say MC had told them about Mr. Galloway more than a year earlier, and what they had observed. The process: They submitted information in writing, were interviewed by Ms. Boyd and then were sent transcripts of their interviews, which they had an opportunity to correct.

Along the way, both say they were told they were going to be treated as ancillary complainants rather than witnesses, as information they had given was beyond the scope of the main investigation involving MC. The women say the reclassification not only confused them, but misrepresented them. They say they were coming forward only to support MC, not to register their own, less-serious complaints. With the change to "ancillary complainant," they feel evidence was gathered under false pretenses.

Communications between Ms. Rooney and the university grew tense. When she was called for a second interview with Ms. Boyd, alarm bells went off. She says she was told she would be asked about the contact she had had with other complainants, about assistance she had received from Mr. Galloway, and her views regarding Believe Women – the movement in support of women who report sexual assault, a phenomenon that has grown in the wake of allegations against comedian Bill Cosby and fired CBC host Jian Ghomeshi – very much in the headlines then.

"Her line of questioning left me very concerned about the direction of her investigation," Ms. Rooney wrote to Prof. Averill, formally requesting that UBC hire a sexual-assault and harassment expert as a consultant to Ms. Boyd. She says the dean, who is currently on sabbatical, declined to make such a hire.

In her report, Ms. Boyd wrote that, when her supplementary statement was returned for editing, Ms. Rooney did not confirm or edit it but instead returned a memo in which she disavowed her earlier recollections. But Ms. Rooney takes issue with the term "disavowed" and says she replaced the transcript from the follow-up interview with written answers to the questions she had been told she was going to be asked.

"She was and is clearly defensive about her role in this matter," wrote Ms. Boyd.

Some complainants with whom The Globe spoke, including Ms. Rooney and Ms. Gemma, were also dismayed over what they saw as a breach of confidentiality. Mr. Galloway was provided with the statements against him and the names of the people making those statements. That's standard practice; for procedural fairness, an employee under investigation must have the opportunity to respond prior to any disciplinary action.

But another student who had come forward as a witness, Anita Bedell, says she was contacted on Instagram by a friend of Mr. Galloway, who said she had seen Ms. Bedell's statement about him. Ms. Bedell was shocked.

"It was expressed to me by UBC that [my statement] would be confidential. And only [Mr. Galloway] would see it and only the investigative team at UBC would see it, including the dean and the higher-ups," she says. "That pissed me off because all of a sudden I felt like I wasn't protected at all."

After expressing her "profound displeasure" to the university, Ms. Bedell was told procedural fairness allowed Mr. Galloway to share complainant or witness statements with his own witnesses, but that the information should have been kept confidential. "Regrettably, what happened, just shouldn't have happened," Jude Tate, then special adviser to the provost, academic equity initiatives, wrote in an e-mail. (Dr. Tate is now director of equity and inclusion.)

When Ms. Rooney also expressed her concerns to UBC about what she'd learned from Ms. Bedell, she was told she did not have a right to know who else had seen her statement and, furthermore, was warned against communicating with other complainants, as it could be viewed as colluding.

"The process was just an absolute ridiculous nightmare," says Ms. Bedell.

Meanwhile, faculty also had apprehensions about how the case was being handled. A meeting was held with representatives from the dean's office during which some of Mr. Galloway's colleagues expressed concerns about the destruction of his reputation.

Susin Nielsen, an adjunct professor in the program and a Governor General's Award-winning Young Adult author who was at that meeting, says she agrees that Mr. Galloway should have been suspended and the allegations taken seriously. "But surely an allegation can be taken seriously, and the appropriate steps can be taken, without immediately going public in such an alarming manner and throwing a valued employee under the bus?" she wrote in a letter to UBC protesting against the handling of the case.

"Because that is exactly what UBC did. I still don't understand why the suspension was made public in the first place, and particularly with such innuendo-laden language."

Faculty were told in the meeting that the university couldn't be held responsible for any conclusions about Mr. Galloway drawn on social media – where speculation about the allegations was rampant after his suspension.

"Fair enough, that's true," says Ian Weir, then an adjunct professor in the program who was also there. "On the other hand, given everything else that was happening at the time, given the fact that the Ghomeshi case was very much in the public eye, [and] deeply distressing facts and allegations concerning Bill Cosby were very much in the public eye, I would be surprised if anybody in the university administration was surprised that those very distressing conclusions were jumped to by the media and by the public."

Ms. Boyd submitted her report to the dean in late April. On May 30, Prof. Averill made his recommendation to Dr. Piper. In June, Mr. Galloway was fired. The university cited "a record of misconduct that resulted in an irreparable breach of the trust placed in faculty members," and stated that Prof. Averill "also took into consideration other allegations" in addition to those investigated by Ms. Boyd. It said Mr. Galloway did not dispute any of the critical findings in the report.

Then the UBC faculty association, of which Mr. Galloway is a member, issued a statement "to clarify that all but one of the allegations, including the most serious allegation … were not substantiated." The implication was that Mr. Galloway did not dispute any of the critical findings in the report because most of the complaints had not been upheld.

But Ms. Rooney and Ms. Gemma say, once they finally saw their copies of the redacted report – which should have revealed everything concerning them – they believe that crucial evidence was missing from the sections dealing with their complaints. For instance, Ms. Rooney recounted an incident at a bar in which she says Mr. Galloway pushed his leg into hers under the table and asked if he would be able to "get a ride on the Rooney train" (meaning sex, she believes, given the context of the conversation) if he were 10 years younger. That story, unlike her other complaints, did not make it into the redacted copy of the report she received.

However, that story was not in the transcript of Ms. Rooney's first interview with Ms. Boyd. But it was included in Ms. Rooney's original e-mail to Dr. Tate at UBC.

"A lot of people are assuming that they know the whole story based off this very minimal report," says Ms. Gemma.

"Somebody has got to come forward and say that it's not right."

Ms. Boyd could not respond to The Globe's queries as she is bound by a confidentiality agreement; she said all questions should be referred to UBC. The university replied that decisions about what Ms. Boyd included and excluded would have been hers. It also reiterated that there was a comprehensive investigation conducted by the dean of arts and that the report was one component. Ms. Rooney was also informed that her statement was included in the report's appendix, read by Prof. Averill, and taken into account when he made his recommendation.

Before receiving her redacted copy of the report, Ms. Rooney inquired about being able to take steps, once she had seen it, if she wanted to contest a finding or the veracity of Mr. Galloway's response to her complaint.

She was told by Paul Hancock, UBC's legal counsel, information and privacy, that he believed once the university had made its findings, that was the end of the process.

In a subsequent e-mail, Mr. Hancock concluded: "I agree with you that UBC's policies should be more explicit about what information all participants receive during an investigation – we are giving a lot of thought to that at the moment."

The fragments of Ms. Boyd's report released to Ms. Gemma and Ms. Rooney state the investigation considered three UBC policies: serving and consumption of alcohol at university facilities and events; discrimination and harassment; and the UBC statement on respectful environment for students, faculty and staff.

While there's no reference to sexual assault in the redacted report, the copies issued to Ms. Rooney and Ms. Gemma reveal other complaints involving alcohol as well as allegations of abuse of power, bullying and harassing behaviour.

The documents show Mr. Galloway was accused of promoting the regular consumption of alcohol and creating a culture in which students felt pressured to participate in drinking sessions on and off campus. He was accused of showing favouritism – offering or withholding opportunities for grad students, for instance. He was also accused of bullying and harassing; of making insensitive, disrespectful, rude comments and of ostracizing and excluding students – undermining their self-esteem and compromising their ability to achieve their study goals, it was alleged.

Ms. Boyd "entirely" dismisses the complaints that Mr. Galloway was "plying" students with alcohol in order to create a sexualized environment or one where inappropriate behaviour on his part would be tolerated. "The reality is that most of the crowd were sophisticated adults … and that [Mr. Galloway] was in no position to control either how much anyone drank nor the conversations they engaged in." She also found that no one was forced to participate.

Favouritism regarding teaching-assistant positions, grants and scholarships was also alleged. The report found that Mr. Galloway may have been in a position to make recommendations, but did not have sole control over those decisions. (However, UBC, in its response to The Globe, indicated that program chairs do make decisions about hiring staff.)

The most serious allegations, those involving the main complainant, are redacted – as are the conclusions.

Ms. Gemma was devastated to see that in the redacted report her evidence was diminished to one brief paragraph that said she described no "personal harassment" toward her by Mr. Galloway, and summarized her concerns that a posting for a job for which she applied had disappeared and the position was later given to someone else.

"It was just this tiny little insignificant thing that makes me sound so petty," she says.

Ms. Rooney had told the investigator about a Facebook comment Mr. Galloway made after she – by now a graduate – posted a photo of her partner, an instructor in the program, dressed as a character from the comic series The Adventures of Tintin. On Facebook, Mr. Galloway referred to "bedroom role play" and later in the thread (which includes responses from Ms. Rooney) wrote: "This whole photo is what would happen if Wes Anderson made an adult film." Ms. Rooney told the investigator she found the comments "very inappropriate and embarrassing" particularly coming from her partner's boss – and in a public venue.

In response to this complaint, Ms. Boyd wrote: "While [Mr. Galloway's] posting may be inappropriate, I am unable, in this context, to characterize [Ms. Rooney's] allegations of harassment as anything other than a gross over-reaction."

It wasn't the only time Mr. Galloway's Facebook activities came up in the investigation. In one thread from February, 2013, when he was teaching in the program, Mr. Galloway, upset that his face with a Grumpy Cat-like photoshopped frown had been posted in a jokey Facebook group, directed this comment to a recent graduate: "My door is forever closed to you. Bear in mind that this community we all travel in is small, and over time being a smarmy little shit will close the walls in on you faster than you can possibly imagine."

The target of this post became a complainant in the investigation, alleging that it was a threat.

According to the report, Mr. Galloway said the post was meant as advice – not a threat. Ms. Boyd ruled that it did not constitute a threat and that both parties involved had acted childishly and inappropriately.

Ms. Rooney was dismayed but not surprised when she read Ms. Boyd's characterization of her in the report, which noted that she was "the one complainant who has most vigorously participated in this investigation," conferring with MC and spearheading the gathering of evidence by the ancillary complainants.

"Suffice it to say that I found [Ms. Rooney] a biased witness, who has perceived every minor incident here through her own tainted lens. I am unable to place much, if any, weight on her evidence. I certainly do not rely on her evidence to support a finding that [Mr. Galloway] is guilty of multiple instances of 'personal harassment'" under UBC's respectful environment statement, Ms. Boyd wrote.

"It's pretty lengthy, the way she dismisses me," says Ms. Rooney. "That hurt."

RAFAL GERSZAK FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The conflicting information they received throughout the process was also distressing for the complainants.

Ms. Gemma was told there would be no announcement as to the outcome; that one day Mr. Galloway could just show up, back at work – or never return.

"I cannot begin to explain the distress, panic, and anxiety that caused me," she wrote in an e-mail to Dr. Tate.

The decision was, in the end, made public, but Dr. Tate subsequently informed Ms. Gemma that UBC generally informs someone whether their complaint has been upheld. Then Ms. Gemma later learned from Mr. Hancock that the only way she could in fact get that information was through the FOI process.

"I am sorry if you have previously received inconsistent information from the university," he wrote.

Some friends and former colleagues of Mr. Galloway aren't impressed with the process, either. Brian Brett, an award-winning author who was an adjunct professor, calls the investigation a "Star Chamber-style kangaroo court."

The investigation has resulted in turmoil at the program, the university and polarizing divides in the interwoven literary community. Mr. Galloway, for instance, was thanked by Ms. Rooney in her acknowledgements for Pedal. He also blurbed her book, praising it as being "written with an unflinching eye and a deep understanding of the torment that is the human condition."

Although UBC says enrolment in creative writing has not suffered, the department has lost two highly respected and popular employees: its program administrator and its undergraduate secretary – the position Ms. Gemma had applied for before the posting was taken down. Having worked for UBC for 10 years, Ms. Gemma resigned in June, saying her personal values no longer allowed her to be affiliated with the university. Andreas Schroeder, who has been teaching with the program for more than 25 years, is resigning at the end of this academic year from his position as Rogers Communication Chair in Creative Nonfiction. While he is of retirement age, nearing 70, the Galloway case was a factor in his decision to leave. Prof. Lyon and Prof. Svendsen, neither of whom spoke with The Globe for this story, are said to be doing their best as program co-chairs, but are stressed under tremendously difficult circumstances in what has been described as a splintered, toxic environment.

For reasons that are not always clear, a number of people teaching in the program have not been asked back. They include Hal Wake, head of the Vancouver Writers Fest, who was an adjunct professor, a friend of Mr. Galloway and has been calling for transparency in the process.

Mr. Brett, also former chair of the Writers Union of Canada, found out he was no longer with the program when he inquired about his UBC e-mail account not working and received a response that e-mail access for "former faculty" had been shut down. "It's rude and shocking for adjunct professors to be treated this way," he wrote in an e-mail to The Globe, adding that he had lost important correspondence and information.

Ms. Nielsen and Mr. Weir, both of whom were hired by Mr. Galloway, will not be returning (Mr. Weir taught his final course last spring; Ms. Nielsen, who has been a vocal supporter of the former chair, is teaching hers now – both positions are being filled by full-time instructors.)

While there has been much chatter speculating that these decisions are related to Mr. Galloway, Ms. Danard at UBC writes that this is untrue. "If your question suggests UBC is retaliating, let us be clear: There have been some faculty changes among non-tenured professors in creative writing that are completely unrelated to this case. It's not unusual for sessional and adjunct professors to come and go in any department at any university."

Saying he is "distressed, dismayed and thoroughly bewildered" by what has transpired, Mr. Weir, an author, screenwriter and playwright, says he is writing a letter to the university demanding disclosure. "Based on the way the situation has been framed and handled by the UBC administration, there is just that dismaying feeling that a terribly difficult situation has been made worse for everyone," he says.

Governor General's Award-winning author Karen Connelly is also planning to write to the university – and went public with her support for Mr. Galloway in a much-discussed Facebook post.

"I cannot remain silent any longer because it makes me want to vomit," she wrote. She reminded people "what a force for [the] literary community he has been – how many students he has helped, to find work, to access agents, to meet publishers – what a dedicated teacher, what a generous, open-minded human he is; what a talented, exacting writer."

Ms. Connelly is particularly disturbed by people's fear of speaking out about what had happened to their colleague.

"Some feared losing their jobs at UBC," she wrote in an interview conducted by e-mail. (Indeed, after the faculty meeting last November, people at UBC were warned against speaking to the media or even to each other.) "But many more feared, and still fear, for their reputations; they do not want to be branded as 'rape apologists' or people who 'do not believe women.'"

Hart Hanson, a 1987 graduate of the program who created the TV series Bones, has also written to his alma mater, stating he would not follow through on a planned donation due to the lack of information about Mr. Galloway's firing.

"My suspicion is that they have messed up for years on sexual harassment issues at the university and then decided to come crashing down like the hand of God on someone and maybe it wasn't quite justified and now they're circling the wagons," says Mr. Hanson, who met Mr. Galloway last year when he received an honorary degree from the program.

But UBC says it can disclose details of employment decisions only if those who resigned or were terminated waive their right to privacy.

Ms. Thien, in standing up for her friend, has waived her own right to privacy in a sense. An intensely private person, she identifies herself as a sexual-assault survivor in her letter, which does not detail the sexual-assault allegation against Mr. Galloway, but lists many of the ancillary complaints. (Ms. Rooney, for her part, disputes some of Ms. Thien's points about Ms. Thien's own role in this.) Ms. Thien also writes that writing faculty called the police in Ohio, when in fact it is not a faculty member heard on the 911 call, which The Globe has obtained.

She says the more serious allegations should have been investigated by the police – not the university. (While UBC could not comment when asked if the university referred this case to the police, Ms. Danard wrote that "generally speaking, it is up to complainants to go to the police if they are the victim of an alleged crime.")

"I believe you have failed everyone involved," Ms. Thien writes. "I know that, if we want a world where women are believed, we must support them to give their evidence without fear or reprisals, in a context in which their identity can be protected and guaranteed by the law, in a system that is transparent and just."

She says that, until the university takes responsibility for its share of the damage done, she no longer wants to be associated with it.

"I do not believe the actions taken by UBC or Creative Writing have made an environment that is safer for women, for victims and survivors of sexual violence, or indeed for any individual.

"Indeed, I believe the university has made it immeasurably worse. I cannot for a moment imagine that any of these events have made the main complainant feel safer, have contributed to her wellbeing, or protected her privacy."

CHRISTINNE MUSCHI FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The investigation has taken a terrible toll on the ancillary complainants with whom The Globe spoke. Ms. Gemma says she has been physically, mentally and emotionally devastated. "I haven't written since this happened; I haven't written a single word," she says. "The core of your identity as a writer is writing. I feel like the core of my identity has been altered in a permanent way."

Ms. Rooney is feeling heartbroken and ostracized from people in the literary community who she says have belittled her complaints. "I thought I was going to be a novelist and that I was going to go to literary festivals and then this happened," she adds. "And that's not my life any more."

Mr. Galloway's life has also been irrevocably altered – his reputation has taken a drubbing and an impact on his career seems inevitable, although his publisher, Penguin Random House Canada, immediately stated its continued support for him last November. PRHC has not responded to subsequent inquiries, including two this week.

"He is a broken man," says Ms. Nielsen. "He's not writing. As far as I know, he's not even reading because he can't concentrate." He declined to be interviewed by The Globe for this story.

He did visit the hospitality lounge at the Vancouver Writers Fest, which wrapped up last Sunday – suggesting an improvement in his state of mind and perhaps an attempt at reintegration. "My understanding is that he realized that he was far more supported," says Ms. Nielsen, who had brunch with him and a group of others last Sunday.

Mr. Galloway, who is divorced from the mother of his children, remarried this year. His wife, who sources say has been very supportive to Mr. Galloway, is a former student; she graduated from the MFA program in November, 2014.

The faculty association has filed a grievance in the case, which is set to go to labour arbitration in March, according to Ms. Connelly. "That is far too slow; it constitutes further punishment in legal limbo for Steven Galloway," she states.

When asked if the university believes the investigation was handled well, Ms. Danard responded, "UBC conducted an impartial, comprehensive investigation that included the hiring of a former justice of the BC Supreme Court."

Ms. Thien's letter, dated Sept. 26, received two immediate responses – one from Prof. Lyon, who says Ms. Thien's name has been removed from all creative-writing platforms. (It can, in fact, still be found – although in most instances, a 404 message pops up.)

A second response from Kathryn Harrison, acting dean of arts, seeks to assure Ms. Thien that UBC is a responsible employer that takes the conduct of faculty, staff and students seriously and that a thorough investigation was conducted, but privacy rights prevent a full explanation. "UBC can weather the criticism that flows from that," she wrote.

Then, nearly a month later, on Oct. 20 – a few hours after The Globe sent more than 40 questions to UBC about the investigation, including points brought up by her letter – Ms. Thien received an e-mail on behalf of UBC president Santa J. Ono from Herbert Rosengarten, executive director of his office.

"This is certainly a sad and regrettable chapter in the university's history," he wrote, reiterating that UBC is required by law to protect the privacy of employees and students unless they waive that privacy.

"All I am able to say is that the university was presented with evidence of behaviour that constituted a serious breach of trust, and sought to act fairly and responsibly in its handling of the accusations against Mr. Galloway. These were very carefully considered by the dean of arts," he wrote.

"In taking the steps that it did, the university believed, and continues to believe, that it acted in the best interests of its students."

There's a line in Pedal, Ms. Rooney's novel – which deals with sexual abuse – that was quoted in The Globe's rave review, and which one can't help but think of when considering this case. It's something her grad student protagonist says to her thesis adviser: "The truth is not simple."

JOHN LEHMANN/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said Hart Hanson was thanked by Chelsea Rooney in her acknowledgments for Pedal. In fact, she thanked Hugh Hanson. This article has been corrected.

Marsha Lederman is a Globe and Mail writer based in Vancouver.

Follow her on Twitter: @marshalederman

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

‘Your offender isn’t a creep’: One woman’s story of reporting a sexual assault

2:00