Legends of Vimy, realities of war

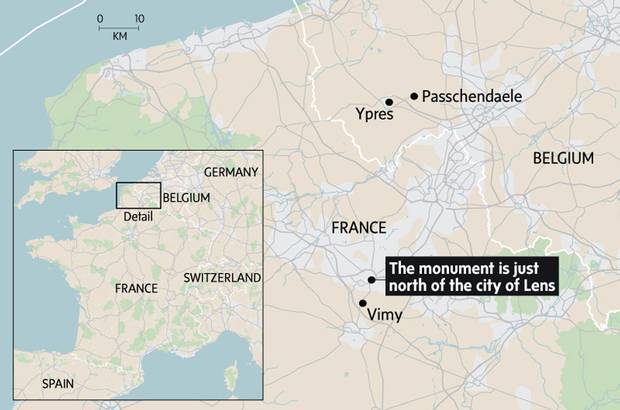

Only four months and a few kilometres of French countryside separated the battles of Vimy Ridge and Hill 70 in 1917. Both claimed thousands of Canadian casualties, but only one is a household name in Canada today. Why?

The notion that this nation was forged at Vimy hinges on some tenuous assumptions about Canada's military role in the world before and after 1917, Robert Everett-Green explains – assumptions that various Canadian prime ministers have carefully cultivated to justify their own military adventures and national myth-building. But recently, historians have been trying to dismantle the Vimy legend:

The past decade or so has been in many ways the climax of the parade, the period of the battle’s widest renown and most unanimous official support. It has also been a time of maximal doubt and equivocation about the battle’s importance in history, its meaning in different eyes, and its right to be hailed as a landmark of Canadian experience. As [Stephen] Harper might have said, we flock to celebrate the battle – 25,000 are expected this year at the Vimy Memorial in France – but we also commit sociology about it.

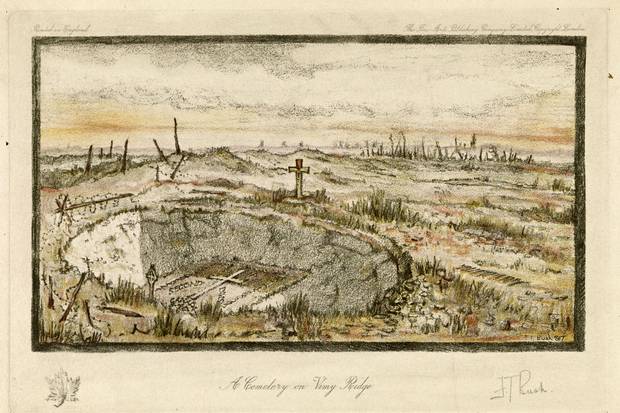

Canadian war artist Gyrth Russell’s The Crest of Vimy Ridge captures the site of a battle where some 3,598 Canadians lost their lives.

Hill 70, meanwhile, was all but forgotten outside of tiny Mountain, Ont., which has its own memorial to the battle. But that's changing, Roy MacGregor writes, as the Hill 70 Memorial Project ramps up commemorations for the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation:

The Hill 70 Memorial Project is spending $8.5-million – none of it government funding – to create a proper monument in the town of Loos-en-Gohelle, France.… Governor-General David Johnston is serving as patron of the Hill 70 Memorial Project, and will be at the April 8 ceremony. As he writes in the introduction to the new book: ‘Canadian successes in the war, Hill 70 among them, helped forge a growing sense of national identity, which culminated in Canada shedding its colonial status and joining the family of nations in its own right.’

Battle for Hill 70: Canada’s forgotten combat of the First World War

TRISH McALASTER/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

TRISH McALASTER/THE GLOBE AND MAIL (IMAGE: GOOGLE EARTH; SOURCE: HILL 70 MEMORIAL PROJECT)

If you're curious about how this newspaper reported the events of the two battles in 1917, here's a gallery of Globe front pages from the time. (It was still just "The Globe" back then; the "and Mail" wouldn't come until the 1930s.) Here's an excerpt from The Globe's report on Vimy from April 11, 1917:

Vimy Ridge has been an historic battleground in this war. The country on either side is dotted with graveyards, in which lie tens of thousands of French and German soldiers who gave up their lives in the fight either to take or to hold this imposing position. The British, too, have tasted of the bitterness of the battles there, and the Canadians had been holding on to a slender position on the western slope all winter only by the display of the most tenacious courage.

Six Canadian soldiers received the Victoria Cross for their service at the Battle of Hill 70. Clockwise from top left: Sergeant-Major Robert H. Hanna; Acting Corporal Filip Konowal; Major Okill Massey Learmonth; Private Harry W. Brown; Private Michael O’Rourke; and Sergeant Frederick Hobson.

BEAVERBROOK COLLECTION OF WAR ART; CANADIAN WAR RECORDS OFFICE; CANADIAN WAR MUSEUM; NATIONAL DEFENCE

Unsung heroes

Six Canadian soldiers won Victoria Crosses at Hill 70 for their bravery on the battlefield. One of these, a ferocious little Ukrainian-Canadian named Filip Konowal, came home from the battle with a disfigured face and serious trauma from his experiences. His life took a dark turn when, once home in Canada, he killed a man and was sent to a psychiatric institution. Roy MacGregor tells the story of his journey from the hero of Hill 70 to a janitor on Parliament Hill:

Hearing of his plight, another VC winner, Milton Fowler Gregg, then serving as sergeant-at-arms for the House of Commons, was able to get Cpl. Konowal hired on as a floor washer. Mackenzie King later appointed him a ‘special custodian’ in the Prime Minister’s Office, where he continued his janitorial duties. ‘I mopped up overseas with a rifle,’ the Victoria Cross winner said in a 1950s interview with the Ottawa Citizen, ‘and here I just mop up with a mop.’

Lest we forget

For The Globe's series, Roy MacGregor took a deeper look at how new initiatives and modern technology are helping Canadians to better remember Canada's war dead. At a high school in tiny Smiths Falls, Ont., he found a group of students tracking down individual soldiers for a massive database of soldier biographies:

The national ‘hackathon’ is studying 1,780 soldiers in detail and, so far, they have made some interesting discoveries. ‘One of the myths is that they were all farm boys,’ says Mason Black, who teaches computer science at the school. ‘The data shows they came mostly from urban areas.’

Readers submitted their stories of family members who served in the First World War. They included Milton Carr, James Moses, John Henry Harvey and George Seadon.

FAMILY HANDOUTS

Your war stories

The Globe asked for readers' family stories of relatives who fought at Hill 70, Vimy Ridge and other key battles of the war. One wrote about his grandfather, a Japanese immigrant to Canada who was lauded for battlefield bravery in the First World War but put in an internment camp as a Japanese-Canadian during the second. Another told us of his cousins Tom Potts and Donald McKenzie from Temagami First Nation in Bear Island, Ont., and how a shaman's prediction about their fate in the war came true:

Though many people on Bear Island were nominally Christian by the First World War, some of the women invited a shaman to perform a shaking tent ceremony to let them know how the boys going off to war would fare. After he came out from the tent, he told the people that all the boys going to war would be injured, except for one who wouldn’t suffer an injury, but all would return home alive. Donald – involved in all the tough fights that involved the 4th Division, including Vimy – returned without suffering a wound. All the other men from Bear Island were wounded overseas.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL