The crude oil involved in a devastating rail accident in Lac-Mégantic last year was drawn from wells in North Dakota, loaded onto trucks and tank cars, and hauled halfway across North America. The Globe and Mail traces the route the crude took from wellhead to disaster and examines how it was classified at each step along the way.

At the time of the accident, the oil was in the least dangerous category that can be applied for a flammable liquid – a classification the Transportation Safety Board later said was incorrect.

However, court documents and public records indicate that several companies had earlier classified the oil as unusually volatile, shedding light on the loose rules governing the classification of crude oil shipments before the derailment.

PRODUCTION

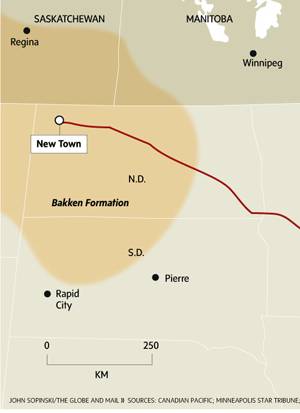

Experts say the Bakken formation, which straddles North Dakota, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, tend to produce oil with a higher quantity of volatile components than traditional crude. This can make the oil more likely to explode if it is exposed to a spark or flame. A class-action lawsuit filed in Quebec Superior Court alleges that the bulk of the oil on the train that crashed in Lac-Mégantic was from at least four different producers in this region, while the Transportation Safety Board has said that 11 different suppliers were involved.

The class-action lawsuit alleges that volatility tests used to determine how crude oil should be classified were generally not performed by producers at wellheads in North Dakota. A PowerPoint presentation by Irving Oil, dated one month before the accident, indicated that a source sampling program to test the crude was “almost non-existent.” However, the Transportation Safety Board said last year that information it was provided by suppliers referenced a range of different classifications, from Packing Group I (the most dangerous) to Packing Group III (the least dangerous).

PIPELINE AND TRUCKS

After the oil was extracted, it was transported by a combination of pipeline and truck, or by truck only, from the wellheads to a transloading facility located in New Town, N.D.

At least two trucking companies involved in bringing Bakken crude to the New Town loading station had classified it as Packing Group II, while at least one other used Packing Group III, according to court documents filed as part of the Quebec lawsuit. (The TSB ultimately determined that Packing Group II was the correct classification for the crude on the train.) However, a lawyer representing the class-action case said he has no evidence that any testing was done by the trucking companies to come up with those classifications.

LOADING

When the crude arrived at a Dakota Plains Holdings Inc. transloading station near New Town, it was moved from trucks into a set of leased DOT-111 tank cars. It took about three truck loads to fill each tank car, according to the Transportation Safety Board, and the train that departed from New Town was carrying 78 carloads of crude.

The crude was loaded onto DOT-111 tank cars, and classified in a bill of lading as Packing Group III, the least dangerous designation that can be applied for a flammable liquid. Concerns about DOT-111s have been flagged by safety agencies in the past, and in March, 2012, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board specifically recommended that government change the rules to require that crude oil in Packing Groups I and II be transported in tank cars that meet higher safety standards. World Fuel Services, which sold the crude to Irving Oil, wrote in a court filing that it was not responsible for classification under Canadian law.

TRANSPORTATION BY CANADIAN PACIFIC

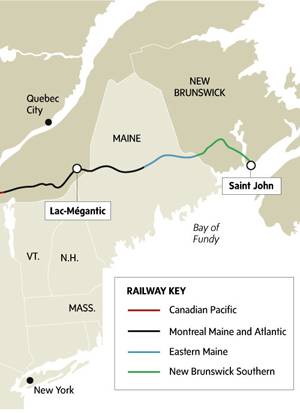

Canadian Pacific took possession of the crude oil and carried it on its most direct route toward New Brunswick: travelling east from New Town toward Chicago. The train rode on another railway’s tracks between Chicago and Detroit, and then travelled on CP’s tracks to Toronto (where it ran parallel to Dupont Street) and Montreal. At some point along the CP route, six of the crude oil cars on the train were removed, leaving 72.

The train’s bill of lading shows the oil was classified as Class III, Packing Group III, indicating the least dangerous classification for a flammable liquid.

TRANSFER TO MONTREAL, MAINE & ATLANTIC

CP handed the crude over to Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway in Côte Saint-Luc, Que. From there, MM&A carried the train along CP tracks to Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Que., and then continued eastbound on MM&A tracks. The load was to be transferred to another railway in Maine, which would have completed the route to Irving Oil’s refinery in Saint John, N.B. But the train didn’t make it that far: After it was parked at the top of a slope, it got loose from its brakes and derailed in Lac-Mégantic, killing 47.

MM&A’s documents also classified the oil as Class III, Packing Group III.

BUYER (never received)

Irving Oil, which has a refinery in Saint John, began buying Bakken crude from World Fuel Services in 2012, according to documents filed in court. A search warrant filed by the RCMP last fall said Irving had received nearly 4,000 rail cars of crude oil from World Fuel Services since November, 2012.

The warrant indicated that Irving typically received Bakken crude that had a classification of Packing Group III. However, the company sent back the empty railcars (which contained crude residue) using the more volatile Packing Group I classification. The warrant also alleged that Irving had access to a November, 2012, test, conducted in North Dakota, that showed the crude should be designated Packing Group I. A spokesperson for Irving Oil said it would be inappropriate to comment on the matter because it is before the court.

With a report from Sahar Fatima in Toronto. Graphics by John Sopinski