A year after the Liberals were elected with a promise to ban the use of asbestos in Canada, no such move has been made – inaction that is dismaying to health experts, labour groups and families affected by asbestos-related diseases.

“Our position, and the evidence, is as clear as it can be: that asbestos is a carcinogen that is a major cause of cancer, including lung cancers, that kill many Canadians,” said Gabriel Miller, director of public issues at the Canadian Cancer Society.

A ban “should be an as-soon-as-possible priority for the federal government,” he said.

Globe investigation – No safe use: The Canadian asbestos epidemic that Ottawa is ignoring

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said the federal government is “moving forward on a ban,” although he gave no timeline and it was not an official announcement. “We are moving to ban asbestos,” he told a conference of building trades unions on May 10. “Its impact on workers far outweighs any benefits that it might provide.”

Six months later, the government says it is “examining” a ban, but provides few details. Questions on asbestos policy were referred to the Minister of Science. But the office of Science Minister Kirsty Duncan declined a request to speak with her.

More than 50 countries around the world have banned asbestos, including Britain, Germany, Japan and, as of this month, New Zealand. Canada – which continues to allow imports and exports of the known carcinogen – was once one of the world’s largest exporters of asbestos, before closing its last mine in 2011. Asbestos was commonly used in such things as roofing shingles, insulation and fire blankets. It is still used in replacement brake pads for cars.

Recent trade data show that asbestos and asbestos-containing products continue to be imported into the country: $4.3-million in the first eight months of this year, according to Statistics Canada. These include pipes, brake pads and raw asbestos.

Meanwhile, more than 2,300 Canadians a year are diagnosed with asbestos-related diseases. The latency period for mesothelioma – a cancer caused almost exclusively by asbestos exposure – is long, typically from 20 to 40 years, and health experts estimate that these cases have not yet peaked.

The science ministry did not respond to questions on the scope of any review, nor did it provide a timeline of when it will make an announcement. It also would not say if it has the lead on the asbestos file.

In a statement to The Globe and Mail, it said the Science Minister is working with colleagues, “using a government-wide approach” to review the strategy on asbestos.

“Our government has been clear that we are taking a different approach [from the previous federal government] to supporting science and protecting the health and safety of Canadians,” said Véronique Perron, the minister’s press secretary. “That’s why we are examining a series of potential science-based actions to further strengthen management and controls, including a ban on the import, manufacture and use of asbestos-containing products.”

The federal government has taken some steps, including measures that will help to prevent accidental exposure by tradespeople, employees and the public. Last month, one federal department – Public Services and Procurement Canada – posted a “national asbestos inventory” of the buildings it owns or leases from. It said other federal departments will follow suit by publishing their own inventories “within the next 12 months.”

The list reveals just how prevalent asbestos is. Of the 2,168 buildings listed, 716 of them have a “known presence of asbestos.” These include buildings across the country, from the RCMP headquarters in Halifax to the stock exchange tower in Montreal, a Statistics Canada building in Ottawa, a Toronto passport office and Vancouver’s international airport.

The inventory list is a “good start,” said Hassan Yussuff, president of the Canadian Labour Congress, noting that it is not yet a full list of all public buildings.

However, Mr. Yussuff is surprised that the federal government has not moved more quickly on a ban, given the dangers to human health. He called on Ottawa to introduce a comprehensive ban on all asbestos products, a move he would like to see tabled in the House of Commons by the end of the year.

“The government campaigned on respecting the knowledge of science and allowing that to guide them in public policy, so this fits with its own approach. It is critical that this be done as a next policy move.”

The World Health Organization says all forms of asbestos are carcinogenic to humans. The most efficient way to eliminate asbestos-related diseases “is to stop the use of all types of asbestos,” it says.

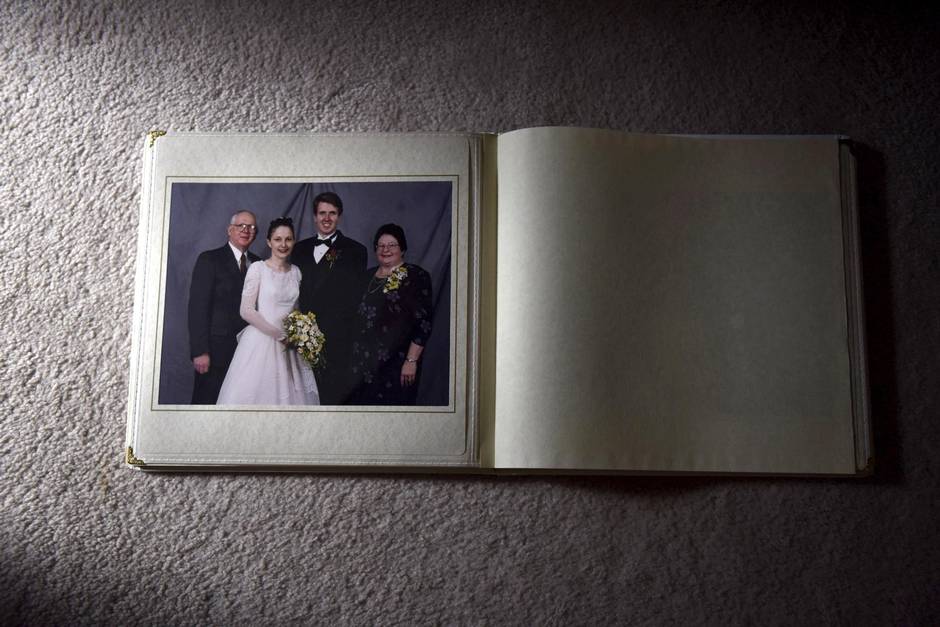

Stacy Cattran, whose father died of mesothelioma in 2008 after workplace exposure in the Sarnia, Ont., area, is frustrated at the slow pace of change.

“It is disappointing that more could not have been done in this first year. They keep making comments that yes, they are planning to move forward with it, but of course just talking doesn’t do it. … If they ban it, that’s going to prevent more deaths in the future.”

Many groups are lobbying for a ban. The Canadian Cancer Society sent a letter to the Prime Minister earlier this year, asking him to ban asbestos. Canadian unions are asking for a ban. At the local level, regional councils and mayors in Niagara, St. Catharines, Sarnia and Essex County in Ontario support a ban. Last month, a petition with 572 signatures calling for a ban was presented to the House of Commons.

Many, including Mr. Miller of the Cancer Society, see a ban as part of a wider strategy to better protect the health of Canadians. This means ending its current use, and more transparency on where existing asbestos is. He would like to see a public registry extended to provinces and municipalities, so that schools, universities, hospitals and all government buildings are included.

This also means tasking one minister who is accountable for developing, co-ordinating and implementing a comprehensive strategy. “The asbestos issue has a way of hiding in plain sight, partly because it ends up hiding in the spaces between political portfolios and between silos within government,” he said. “And with a busy agenda … it would certainly be easy for this sort of issue that requires work across government to get put off. And we absolutely can’t allow that to happen.”

Wally Rogers, in Kamloops, B.C., is one of many workers who were exposed to asbestos on the job – in his case, as a labourer at a smelter and as an auto mechanic. He recalls using gloves with asbestos padding to handle hot zinc ingots. No employer ever warned him about the health risks of exposure.