With a short hop off the bow of a Zodiac, Roger Hitkolok came ashore to the site of some of his earliest memories. Putulik, known in English as Sutton Island, is a barren, inhospitable heap of rock rising from the Dolphin and Union Strait. It's one of a cluster of three small islands located 125 kilometres northeast of Kugluktuk, Nunavut. There's little vegetation and less freshwater; its lone apparent attraction is its small harbour, surrounded on three sides by a steep, off-white cobble beach and rocky hills.

Mr. Hitkolok, 69, returned to the island periodically during the course of his life. Burnt driftwood, from a campfire his grandchildren made during his past visit in 2015, lay steps from where he landed.

But this visit was different. To begin with, it was the first time he'd arrived on a 73-metre Canadian-flagged icebreaker. Mr. Hitkolok boarded the Polar Prince in Kugluktuk as a participant aboard Canada C3, a 150-day voyage from Toronto to Victoria via the Northwest Passage. Others aboard the icebreaker regularly plied him for experiences and observations gleaned from a life lived in the North.

And it was through one of his stories that more fragments of Sutton island's obscure history came to light. For it would soon be apparent that others had also found shelter there. They, too, left signs of their passing.

Mr. Hitkolok's story goes like this: Some time during the early 1950s, he, his parents, siblings and a family friend were returning home to Read Island (located about 37 kilometres due northeast, just off the south coast of the Wollaston Peninsula) after delivering supplies to his great grandparents in Bernard Harbour, a bay on the mainland of what is now Nunavut.

"All of a sudden, the wind picked up from the west," he recalled. So they took shelter in Sutton Island's harbour. The raging wind changed direction as they slept, splintering their eight-metre wooden boat on the rocks. "The tent was flapping, we couldn't hear it," Mr. Hitkolok said.

So Mr. Hitkolok, then about five years old, found himself marooned. He recalled his parents being untroubled by their predicament. The family subsisted by hunting seal, rabbit, seagull and ptarmigan (a common Arctic game bird) each day. Boredom, not survival, was the greatest concern. "We just had to wait until someone came by," he shrugged. "They were ready to make a fire on the shore if they heard a plane."

But the only planes passing by flew through impenetrable fog. The family waited three months for the surrounding waters to freeze. Then the family friend ran the 25 kilometres across the ice to Bernard Harbour to summon help. His uncle picked the family up with a dog team. The bannock Mr. Hitkolok ate then was the tastiest of his life, he said.

This story prompted polar explorer and C3 expedition leader Geoff Green to request the Polar Prince make an unscheduled stop. "At the last minute, we said, 'Let's go have a look at those islands,' " Mr. Green said. That led to the Polar Prince planting its nose on the harbour's stone beach as Mr. Hitkolok pumped his fists in the air. Mr. Hitkolok was among the first ashore.

The Canada C3 vessel Polar Prince goes ashore at Sutton Island.

PATRICK DELL/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The stony beach of Sutton Island’s small harbour is one of the few apparent attractions in a place with little vegetation and less fresh water.

PATRICK DELL/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Roger Hitkolok, 69, was among the first Canada C3 passengers to disembark on Sutton Island. He has returned to periodically throughout his life.

PATRICK DELL/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

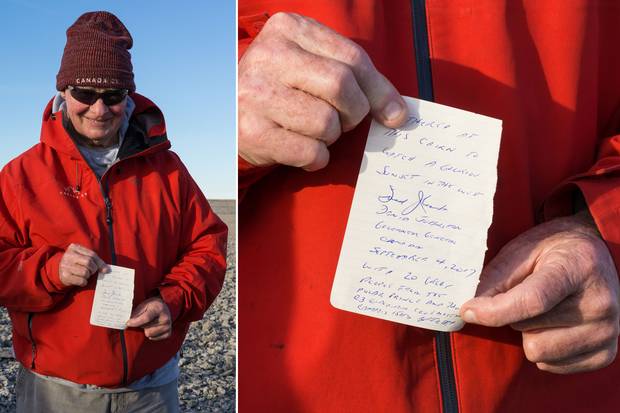

Governor-General David Johnston wrote a note to leave in a cairn on Sutton Island.

PATRICK DELL/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Soon after landing, Mr. Green noticed a cairn covered in orange lichen at the top of the beach. Having found a note stashed in a similar cairn years earlier, he moved in for a closer look. Inside this cairn, he found a rusted metal container. It contained a letter, slightly stained but still entirely legible. It read as follows:

Tom Camsell and His crew found shelter here from a Terrible Storm on Aug. 23th 1986 in the year of our lord. Signed Capt. Tom Camsell, M.V. J. Mattson

Video Watch the discovery of the note in the cairn

Born in Hay River, Northwest Territories, Tom Camsell followed the horns of the Mackenzie River tugboats that sailed from that community. He worked for several transportation companies in the Arctic, resupplying northern communities and Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line sites. "I still run across people that ask me if I'm Tom's brother when I travel in the Arctic," wrote Terry Camsell in an e-mail. (Terry Camsell followed his elder brother into the North's shipping industry, and is now the manager of business development for Fathom Marine in North Vancouver.)

Crewmember Terry Anthony recalled that the J. Mattson was headed west toward Tuktoyaktuk in 1986 when they encountered a violent storm. "Being on the J. Mattson, a river tug with no real draft, we had to find a place to hide," Mr. Anthony recalled in a written account. The crew remained there for three days, waiting for the weather to improve.

"We walked [the] whole island and found a human skull on the beach about half way around the edge," he wrote. "Also remember there was a cave not far away from it in a rock bluff that had bones in it." Before leaving, they saw a cairn and placed their note inside.

Capt. Camsell died suddenly on the deck of one of his ships in 1991, felled by a brain aneurysm, at the age of 44. His daughter, Sandra Tuccaro, was just 13. Contacted by e-mail, she knew nothing of her father's visit to Sutton Island; she had only photographs depicting fragments of his maritime career. "His death left a huge void that has never been filled," Ms. Tuccaro wrote. "He was a captain, hunter and trapper, an awesome guitar player and one hell of a guy."

C3 participants recognized that one of Ms. Tuccaro's photographs depicted Capt. Camsell standing next to the very same cairn on Sutton Island, the J. Mattson visible in the distance. This revelation "was like it was my dad coming through you to let me know he is okay," Ms. Tuccaro responded by e-mail.

Stranger still was the revelation that the seemingly desolate Sutton Island once harboured residents who sought more than shelter.

As Governor-General David Johnston, another C3 participant, penned his own letter and placed it in the cairn, archeologist and cultural anthropologist Brendan Griebel found himself drawn to a curious configuration of mossy stones some tens of metres away. To the uninitiated it resembled no more than a crude, abandoned fire pit. But Mr. Griebel, who has studied the peoples who've inhabited the Arctic over the past 4,500 years, was that rare individual equipped to grasp its significance. He found at least 20 similar stone arrangements – some circular, others rectangular – as he climbed higher.

These scattered structures appeared to date from different eras. At the island's highest reaches, he found what he identified as communal houses from the Middle Dorset period (approximately 200 to 400 AD). He suspected they once resembled modern tents, with rocks holding the hides in place, but it's impossible to know for certain. "We've never found one intact," Mr. Griebel said.

Mr. Griebel wasn't aware of any Middle Dorset communal structures discovered this far west. That so many structures should be found in such a barren place perplexed him. "I wasn't expecting much, to be honest," he said. "It's not a good place to live."

Research into the North's ancient inhabitants is still in its infancy. University of Toronto anthropology professor Max Friesen (Mr. Griebel's thesis adviser) published a paper about other alleged Middle Dorset sites last year. He acknowledged an extreme lack of data; his own observations were confined to brief site visits by helicopter, some lasting mere minutes. Mr. Griebel saw no evidence any Sutton Island structures had been excavated, and doubted they ever will be.

"No one will ever have an idea of what that was doing there," he said. "Which I like. It's an enigma sitting on an island in the Arctic that doesn't make sense to me, and probably never will."

Mr. Hitkolok didn't recall encountering the stone configurations during his childhood, and was similarly mystified about the people who made them. His thoughts dwell instead on his father and older brother, both now deceased.

And he thought about passing traditional Inuit knowledge to youth. "There's always some way of surviving," he said. "It's important to pass those skills to our grandkids."

CANADA C3'S JOURNEY: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Video A day in the life aboard Canada C3