Decorators were frantically painting, vacuuming and sliding furniture into place last Wednesday at the newly refurbished Canada House in London. More than a year after the High Commission launched a meticulous $20-million revamp of the tired Greek Revival building, everyone from anxious royal liaisons to hustling cleaners to the hyper-vigilant High Commissioner Gordon Campbell was working overtime ahead of the first-ever consolidation of Canadian diplomatic activity in Britain. In each room – one for every province and territory, and more for former prime ministers Mackenzie King, Borden, Macdonald and Laurier – gallery plaques were shifted into place alongside one of the largest Canadian art collections outside the country. At 11 Thursday morning, the Queen arrived in turquoise tweed for the reopening, heralded by a parade of Mounties. She signed the guest book, unveiled a gilded plaque by the entrance and shook hands across the new Canadian red oak floor.

Since signing a Joint Declaration three years ago, Canada and Britain – the only countries to share membership in NATO, the G8, the G20 and the Commonwealth – have forged a strategic partnership to increase economic growth, trade and security, making London one of Canada’s most important embassies. The hope is that the country’s culture and values come through in the extraordinary quality of fine art, furniture and workmanship – not only from the urban centres but from sea to sea to sea.

It was a stroke of real estate prescience that landed Canada’s High Commission this prime corner of Trafalgar Square. Australia’s and India’s are a kilometre east on the Strand, but Canada House is dead centre in London, the point from which all destinations are measured. The former Union Club – designed by British Museum architect Robert Smirke – became Canada’s in 1923 for less than $500,000 after the government moved to centralize its 200 employees in the capital. In 1925, it was King George V who formally opened the doors to what was then a warren, to be navigated by every Canadian globetrotter needing a passport, a job or, in the case of the Prime Minister, a place to lay a briefcase.

Since then it’s been a long, somewhat strange trip. During the war, High Commissioner Vincent Massey ran a pub in the basement for Canadian soldiers, and during the Blitz, the building – and Lester Pearson, Massey’s then-secretary – was very nearly destroyed by a bomb landing 20 metres away. In 1993, Brian Mulroney closed the building to cut costs; then Jean Chrétien revived it. Before the 21st-century days of baggage scanners, Canada House was a place homesick tourists could shake off their flag-embroidered backpacks and read a (day-old) Globe and Mail. But the diplomatic functions had become increasingly fractured after the High Commission opened a residence and chancery in the 1960s in a Georgian pile in Grosvenor Square.

Running both was expensive and illogical. Last year, the government sold the chancery for just less than $600-million and channelled a portion of the earnings into the revamp. The yellowing walls were repainted a glowing shade of white the Inuit would surely have a name for. Ceilings were raised, skylights opened up and decades of bad conversions eradicated as restorers replaced missing crown moulding and decorative panelling. “The sixties have a lot to answer for,” says Cindy Rodych, a vice-president at Stantec, the Edmonton-based architecture practice that won the contract for the top-down redesign. Stantec even converted a cupboard-sized water closet into an elaborate staff bathroom with an original marble fireplace and Regency chandelier.

Today, Canada House acts as an envelope for contemporary credenzas resembling lobster traps (in the PEI Room) and painterly rugs by Winnipeg’s Denise Préfontaine. As High Commissioner Campbell told me, “We want to show Canada, not tell Canada. The vast array of Canadian talent is clear here.” An adjacent structure built by Sun Life Canada in the 1920s now connects to the south façade via a cascading staircase and a feature wall panelled in Canadian hemlock. A second gallery entrance leads to a vaulted exhibition space hung with five new Jeff Wall photo montages; the exhibition space is open to the public. The quality of natural light circulating throughout the reopened space is awe-inspiring – like the big Prairie sky. Just as striking is the colour radiating from every surface. “I’m all about colour,” Mr. Campbell says. “Canada’s not grey.” He sweeps through the Saskatchewan Room and taps the back of a leather meeting chair. “Roughrider green,” he says. “The pièce de résistance.”

Ms. Rodych reckons close to half the furniture she plucked for the interiors was created by lesser-known craftspeople, some of whom met the Queen on Thursday. Ms. Rodych worked with Dan Sharp, the Department of Foreign Affairs’ art curator, to import art from New Brunswick’s Anna Torma and Northwest Territories’ Helen Kalvak to Charles Pachter and Emily Carr. The quality and provenance are simply staggering. Any Canadian passing through town can secure a meeting room or attend the robust schedule of events – just next week is a reception with London-based Canadian fashion designer Thomas Tait. We may be past the age of popping in with a backpack; stepped-up security means you have to book ahead. But when you do, there’ll be a Benson sofa waiting by the Brent Comber coffee table in the lobby. And on a plinth by the stairs, just for good measure, Gathie Falk’s pile of 14 ceramic snowballs.

Entry Hall table

With their totemic carved panels, Sabina Hill’s First Nations collaborations could be from nowhere else but the Pacific Northwest. Alongside Yukon Tlingit artist Mark Preston, the Port Moody, B.C., artist designed the evocative entry-hall Signing Table, carved from Western red cedar with a textured black walnut frame topped with glass. A bronze anodized-aluminum plaque under the glass features three Tlingit watchmen. “Their supernatural powers allow them to see far off into the horizon in both the natural and spirit worlds,” Ms. Hill says. Though her subject matter is steeped in tradition, Ms. Hill achieves her bold Northwest Cost carvings through CNC technology that guides a router to hone the wood, a merging of old and new that represents Canada House itself.

Pacific Room

Canada House ran a competition for artwork – largely to be translated into area rugs for the palatial reception rooms – and selected several works by Nova Scotia painter Wayne Boucher. Carol Sebert of Toronto rug-design company Creative Matters was tasked with interpreting Mr. Boucher’s ethereal ocean scenes into carpets that are durable yet rich in colour. “Some of them are the most complicated things we’ve ever done,” Ms. Sebert says. For this room, she and her tufters recreated Mr. Boucher’s Waiting for London into a 32-colour carpet of sharp blues and ambers roughly 10 by 14 feet. It took nearly 100 hours to complete, reconstructing each piece of yarn into stipples of blended colour. “It was like doing a pointillism painting,” Ms. Sebert says. “If it’s one colour that carries through, it’s the blues. You can really feel the ocean. The blues are icy cold. It’s very Canadian.”

Stairwell light

It took a team of rappelling workmen to install the scattering of amorphous blown-glass bulbs by Omer Arbel, founder of Vancouver lighting practice Bocci. “In my mind’s eye,” the designer says, “I saw it as a kind of underwater creature, floating in the stairwell with little regard for gravity.” The mirrored-glass globules blast out from several points on the heritage-listed skylight. This forced Mr. Arbel into a back-and-forth with English Heritage that netted “a perfect balance that respects the most sensitive historic fabric of the building and still allows it breadth and power. New and old achieve balance together.” Voids of different sizes in each grey-glass bulb come alive when lit, creating a “controlled chaos” that responds poetically to its surroundings. He stops short of calling it a chandelier, though. “I’ve switched to thinking of our projects as ‘installations,’” he says. “There are sculptural motivations to the work that go far beyond lighting.”

Nova Scotia Room

Cindy Rodych of Stantec asked Earltown, N.S., woodworker Jonathan Otter to create two maple tables with square tapered legs, round aprons and pinned mortise-and-tenon joinery. The design itself is not uniquely Nova Scotian as such, Mr. Otter says, but it does reflect the simplicity of Nova Scotian craft. “Here in Colchester County where I live, there settled a large contingent of Empire Loyalists who fled the revolution in America,” he says. “Their furniture reflected not the elaborate styles available from the city workshops but a simplified style in locally sourced woods that was more easily accomplished by the craftspeople who lived there.” The biggest challenge, he says, was producing a red wash that showed the wood grain, testing numbered samples with different methods and varying coats.

Carved-glass wall

For the newly opened top floor of the building, artist Warren Carther installed a wall of glass that reflects on the origins of Canada as a British colony. Mr. Carther, whose glass work stands in the Canadian embassy in Tokyo and the Winnipeg airport, references the beaver in dark swaths of glass, highlighting the jumping-off point of the two countries’ partnership. In tidy horizontal rows across the installation, 93 cylindrical dichroic-glass forms are meant to represent falling snow. “Each snowflake exhibits its own unique hue, shifting in colour as you walk past the work, creating a kinetic visual experience,” Mr. Carther says. “The contrast between the fur-like texture of the dark, almost opaque rectangular form and the colourfully illuminated glass provides tangible counterpoints. It reflects the vast breadth of qualities that make Canada so diverse.”

Manitoba Room

J. Neufeld of Wood Anchor sourced the 200-year-old Manitoba oak for this grand conference table from a small stand earmarked for development on the Red River watershed. “Many developers now call us prior to removing these trees so we can assess which ones we’d like to repurpose,” Mr. Neufeld says. He carefully selected the 12-foot-long cracked butterfly flanks to keep their shape in London, despite the change in climate. “The widening of the ‘wings’ locks the piece into the tabletop, preventing the cracks from shifting and widening,” he says. “The butterflies also act as a bridge between the two pieces, much like the bridges we have in southern Manitoba that connect both sides of the mighty Red River. If you understand wood, you can see the harsh winters in the grain.”

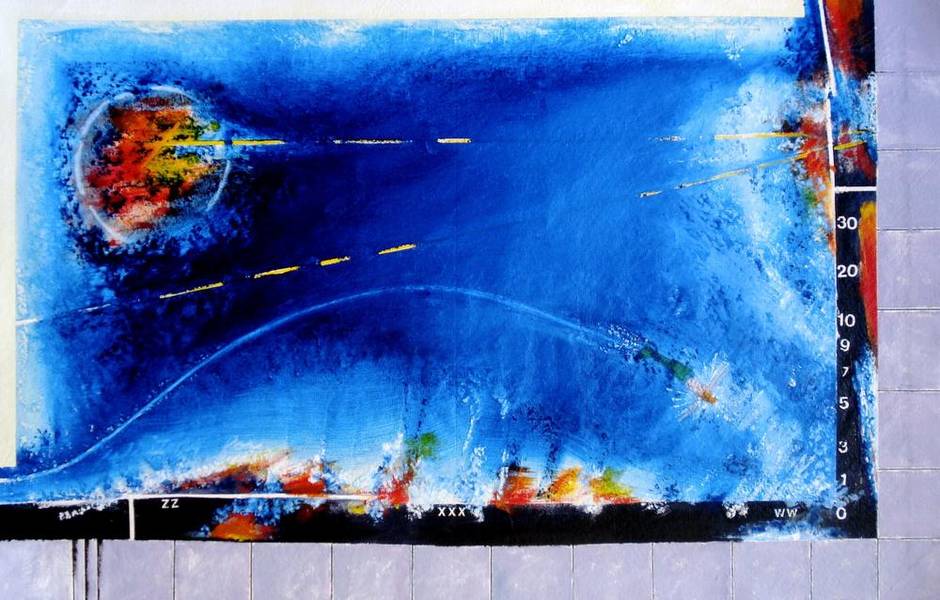

Newfoundland Room

St. John’s-based artist Will Gill submitted a cropped image of his acrylic painting Ocean to the competition, and Creative Matters translated the expressive brushstrokes into this immense floor covering. “I actually work on most of my paintings with the canvas directly on the floor, so in this case the image returns to the place it originated.” He says the palette of blues against the muted background speaks to the spirit of his home province. “It’s an expression of movement, vigour and life that is so much a part of everyday existence in Newfoundland – could be wind patterns, could be an iceberg slowly tracing a course on the ocean. When icebergs float by the narrows of the St John’s harbour in spring, the sea becomes an ever-changing landscape, an active landscape.”

Quebec Room

From the countryside near Sherbrooke, Que., comes a pair of wood benches by Kino Guérin, made from loops of wood without added legs, crossbars or supports. The seamless seats are composed of layers of black walnut, glued one over the other to help the piece bend and twist into light, fluid shapes. “Black walnut is one of my preferred woods – different from European walnut and a good wood to represent our country,” Mr. Guérin says. The designer developed the bent lamination technique over some 20 years, using a series of moulds and a vacuum press. “There’s no one secret to it,” he says. “The overall look is a cross between European and American styles,” he says, “modern and simple like the Europeans and funky and exuberant like the Americans.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said Stantec was based in Winnipeg. This version has been corrected.