Lionel Desmond, far right, was part of the 2nd battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment, based at CFB Gagetown. Here, he is shown in 2007 in Afghanistan’s Panjwai district, in between patrol base Wilson and Masum Ghar.Trev Bungay/Facebook/The Canadian Press

Behind the vinyl-clad trailer on the hill, the tires on Shanna Desmond’s newly leased red Dodge pickup truck are flattened, punctured by knife marks.

Shanna's father, Ricky Borden, is standing in the driveway, which has been churned into a mud pit by the steady stream of police and medical-examiner vehicles. He and a friend fortify themselves with bottles of beer before going inside to tackle the grimmest of tasks: patching the bullet holes that now riddle the walls and ceiling of the home. "Can you imagine having to do that?" he said, staring straight ahead.

Inside the neatly kept trailer in Upper Big Tracadie, N.S., there are blood stains on the beige seats of the bar stools at the kitchen island where Shanna stood; the grout on the kitchen tile floor is tinted darker than the rest. The family's toy poodle was here when Lionel Desmond arrived on Jan. 3. The dog now shakes incessantly, traumatized by what happened when the 33-year-old Afghan war veteran walked into the trailer.

Some time around suppertime, he stepped inside – moving past a decal on the wall that read "Home is where the heart is" – and shot his wife, Shanna, and 10-year-old daughter, Aaliyah, and his own mother, Brenda Desmond. Then he killed himself.

"He went in that house on a mission and there was no way to escape even if they tried," Shanna's mother, Thelma, says. "Whoever was in the house was his target."

Shanna Desmond’s mother, Thelma Borden, holds Penny G, her granddaughter Aaliyah’s dog, outside her home where the killings took place.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

Nearly six months later, the Bordens and Lionel’s family members are still struggling to understand what happened to Lionel Desmond – and to what extent post-traumatic stress disorder and the support he received after returning from war contributed to the tragedy that has destroyed their families. They desperately want answers, and are calling for the Department of National Defence and Veterans Affairs Canada to investigate the treatment Lionel received during and after his military service. But the federal government doesn’t appear interested in calling for an inquiry into the tragedy, despite the lessons it might provide about what soldiers endure during military missions – and what sort of additional support they need to reintegrate into civilian life.

Lionel is one of more than 70 soldiers and veterans who have killed themselves – and in rare cases, others – after serving in the Afghanistan war. Over the past six months, The Globe and Mail interviewed more than two dozen of Lionel's and Shanna's family members, friends and military colleagues to piece together how the unthinkable happened in this remote Maritime community. In many respects, the investigation has turned up more questions than answers. For now, the families say they are certain of only one thing: Lionel Desmond is a soldier who slipped through the cracks.

A photo of Lionel and Shanna with baby Aaliyah hangs at his uncle Allan Desmond’s home in Lincolnville, N.S.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

‘No training in the world could get you ready for that’

Before he went off to war, Lionel Desmond was a happy-go-lucky guy who was often thoughtful and always ready with a joke. "You couldn't get a funnier, sweeter person in the world than Lionel Desmond," said Jenna Belony, a childhood friend who first met Lionel in high school. "Any time I had a bad day, he'd always say, 'Tomorrow is a new day. Smile for that.'"

Lionel lived to make people laugh and smile. He even tried to get Shanna to crack one while she was in labour with their daughter in December, 2006, by copying her breathing and pretending to push. (Shanna, however, was not amused.)

Lionel was proud of his job as an infantryman with the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment based in CFB Gagetown, N.B., and hung his framed Canadian Oath of Allegiance on the wall in his grandparents' kitchen.

He brought his trademark humour to Afghanistan, where he was deployed in January, 2007, just a month after Aaliyah was born. After arriving with No. 9 Platoon in Kandahar province, Lionel quickly became known as an entertainer, exaggerating his northern Nova Scotian accent and breaking into James Brown song-and-dance routines. His fellow soldiers nicknamed him Dezzy.

"For the first two months, it wasn't that bad," said Lionel's best friend, Orlando Trotter, a retired corporal, describing life in Afghanistan during the beginning of their tour. They lived in an abandoned compound called Strong Point West. "It was kind of quiet." During downtime they lifted weights, cleaned their guns and watched movies like Flags of Our Fathers and Superman Returns.

After a few months, however, life on the base became more tense – just as Lionel and Mr. Trotter received some devastating news. Six of their comrades had died when their light-armoured vehicle hit a roadside bomb. Five were from Lionel's base, Gagetown: Sgt. Donald Lucas, Cpl. Aaron Williams, Pte. Kevin Kennedy, Pte. David Greenslade and Master Cpl. Christopher Stannix. Mr. Trotter said the deaths took a toll on him and Dezzy. But there was no time to mourn their comrades. Lionel's platoon – which had moved to Masum Ghar base in the dangerous Panjwaii district of Kandahar province – was focused on aggressive attacks against the Taliban. Bullets whizzed all around Lionel and his comrades during daily gunfights, said former master corporal Trevor Bungay, who was the second in command of Lionel's platoon in Afghanistan. "Close calls were a daily event," he said.

Many times, the platoon set out at 2 a.m. and was in position by dawn, the call to prayer echoing across the desert. When prayer ended, the soldiers attacked. The 24-year-old rifleman's job was to hunt down and kill the Taliban. He also carried the wounded on stretchers and collected corpses – arms, legs and heads – and put them on vehicles to take to an Afghan police station.

"No training in the world could get you ready for that," said Mr. Trotter.

Lionel Desmond, right, and his friend Orlando Trotter in Afghanistan in 2007.Courtesy of Orlando Trotter

Lionel’s sister Chantel Desmond, right, shown with Lionel’s daughter Aaliyah in August, 2016, said her brother’s eyes were ‘just dark’ when he arrived at the airport coming home from his service in Afghanistan.Courtesy of Chantel Desmond

Haunted at home

Chantel Desmond says she noticed a vacant look in her brother's eyes when she and other family members picked him up at the airport in August, 2007. "His eyes were just dark," she said. "It wasn't Lionel."

Back on base in Gagetown, Shanna Desmond confided in Mr. Trotter that her husband was suffering from "shell shock." At the time, Mr. Trotter said he didn't think much about the comment, because many of his comrades were also struggling – though not necessarily seeking help. "There's a stigma that you don't want to ask for help because it'll impact your career," he said. "A lot of guys are scared to lose their job – get kicked out of the military. It's difficult when you have a family, mortgage and car payments."

It's unclear exactly what Lionel did in the infantry over the next two years, though in Veterans Affairs documents he said he hadn't been able to perform duties after 2008. He wanted to change trades and become a mechanic, but was sent to the musical pipe-and-drum unit in 2010 instead – a move that upset him. He felt frustrated and disillusioned with the Canadian Forces, family members say, and a former colleague added that Lionel believed the new band position was a "wimpy" job.

A sign of Lionel's growing instability surfaced in a field mess hall one day after his transfer. A fellow soldier jokingly asked him why he was drinking chocolate milk. Isn't white milk good enough, he'd asked. Lionel erupted, jumping out of his chair. He grabbed a knife and chased the soldier out of the mess hall. Later, Lionel described how upset he was to Shanna's aunt, Sarah MacEachern. "He said, 'I would've killed him if I had've got him,'" she said.

He had a similar conversation with Cpl. Rick Pitchuck, a fellow Nova Scotian, from Cape Breton. Lionel also talked about how doctors thought he was going "crazy," as Mr. Pitchuck, now retired, recalls it, and that he had a "friend" in the back of his head who was always talking to him. But he tried to make light of it. "He just laughed and said, 'He's there all the time and won't go away,'" said Mr. Pitchuck. "I never really had any concerns, because he told me he's going to get help about it."

Shanna eventually convinced Lionel to go for help at the medical clinic on the base, where he was referred to Dr. Vinod Joshi, a National Defence consultant psychiatrist, who first assessed him in 2011 and continued to see him once a month. A letter to Veterans Affairs – written later at Lionel's request – described Lionel as a changed man. He'd lost interest in life, Dr. Joshi said, and was withdrawn and emotionally numb around his family.

At night, he was tormented with nightmares and insomnia. During the day, his mind flashed back to carrying body bags and corpses. He felt guilt about Afghan civilians' deaths, even though he wasn't the direct cause. And he was disturbed by an unexploded IED that was detected on a bridge he had just travelled across. What haunted him most, however, was a vivid mental image of an Afghan man who he thought was staring at him, only to discover it was a body covered in flies.

In a separate document dated Sept. 28, 2011, Lionel was diagnosed with PTSD with major depression and depressive episodes. The assessment also showed that Lionel was on "Temporary Category," a designation that indicates a soldier has an illness or injury that may limit the type of work they can perform.

To be diagnosed with PTSD, a soldier has to experience a range of symptoms, including nightmares and flashbacks, hypervigilance, reckless behaviour, sleep disturbances, irritability and angry outbursts, persistent and distorted sense of blame, estrangement and diminished interest in activities for more than one month. Once diagnosed, soldiers are sent to an Operational Trauma Stress Support Centre, where an individual treatment program is created. In Lionel's case, he was advised to start attending trauma-focused psychotherapy and a psychoeducational group and to bump up his drug regimen. In addition to boosting his dosage of Effexor, an anti-depressant that he was already taking, and continuing to use a sleep aid (Zopiclone), he was told to start taking an antipsychotic medication (Risperdal) daily and a sympatholytic drug for anxiety and PTSD (Prazosin).

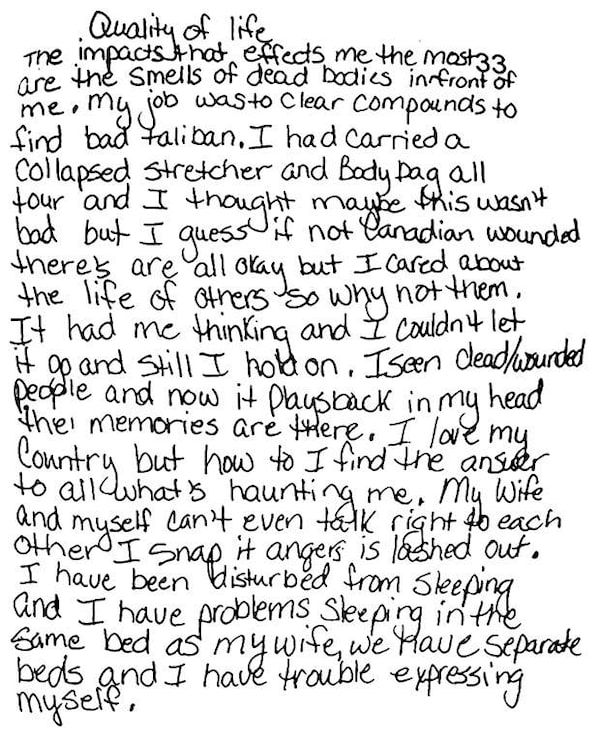

About a month later, Veterans Affairs received a handwritten document from Lionel. In it, he described changes to his quality of life after serving in Afghanistan, writing that he loved his country but was haunted by "the smells of dead bodies in front of me," and that he had trouble feeling close to Shanna: "I have problems sleeping in the same bed as my wife."

He also wrote that he took part in a PTSD program and learned breathing techniques: "I'm learning to control but sometimes it doesn't work. I blow a head gasket and it's like the war is just beginning.

"I have been paranoid looking over my shoulder. I don't like big crowds, drives me to be more alert and on guard."

Lionel Desmond wrote about how post-traumatic stress disorder affected his quality of life for a Veterans Appeal and Review Board review.

Thelma Borden said she told her daughter to go easy on Lionel because he had been through so much in Afghanistan. But there were times when she visited the family in New Brunswick and couldn't put up with her son-in-law's angry outbursts and insomnia. She'd leave early, sometimes taking Aaliyah with her.

Lionel took a turn for the worse in spring, 2012, when he began to develop obsessive-compulsive traits, according to a note to Veterans Affairs by Dr. Joshi. He continued to have significant problems with PTSD and deteriorated further in the fall, when he and Ms. Desmond separated. (Ms. Desmond's family says they didn't split up, but rather that Shanna had moved back to Nova Scotia to attend university and become a registered nurse.)

"The thought for him of losing his daughter and his wife, not being able to be a good dad and a good husband, I think that angered him. With post-traumatic stress disorder, it's very hard to think straight, so you do have outbursts, and sometimes he would do that," said Mr. Bungay, who was also stationed in Gagetown after returning from Afghanistan.

Lionel's mood was depressed, Dr. Joshi noted. He had occasional dissociative experiences, persistent problems with hypervigilance, road rage and anger, and frequently thought about suicide, though he had no specific plan in mind.

On a scale of 10 to 100 to measure how well a person functions in daily life, Dr. Joshi rated Lionel's ability at 55 to 60 – meaning he had moderate difficulty in social, work or school functioning. Optimal mental health is in the 91 to 100 range. Overall, Dr. Joshi wasn't optimistic about Lionel's future. "His long-term prognosis is guarded in light of poor response to treatment." (When contacted by The Globe and Mail, Dr. Joshi declined to provide further comment though a National Defence spokesperson, citing patient confidentiality.)

Dr. Joshi submitted his assessment as part of an appeal Lionel made to Veterans Affairs to increase his disability compensation. After reviewing details of how PTSD had affected his life, the Veterans Appeal and Review Board bumped up his one-time award by a few thousand dollars, to $74,646.

Headstones, including those of other soldiers who served in the Canadian Armed Forces, rest near Church Cove behind St. Peter’s Parish in Tracadie, N.S., where Lionel and Brenda Desmond’s funerals were held.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

Family beginnings

The string of forested communities where the Bordens and Desmonds live near the northern tip of mainland Nova Scotia has a unique history. Many of the African Nova Scotians who live here are related through the 74 original black Loyalist families that settled more than 200 years ago, after the American Revolution. Life was harsh for the new settlers as they struggled to work the infertile land and deal with inimical neighbours and broken promises from the British.

Lionel grew up in Lincolnville, an isolated African Nova Scotian community near the coastal village of Guysborough. The Desmonds have lived here for at least five generations. Lincolnville was home to Canada's last segregated school, which closed in 1983 – the same year Lionel was born.

Lionel lived in his grandparents' tiny bungalow with his mom, four younger sisters, as well as some aunts, uncles and cousins – about a dozen relatives altogether. His father, Kenneth Jones, lived a few doors away for most of Lionel's childhood, but he was raised solely by his mother, Brenda Desmond.

Lionel Desmond’s twin sisters Cassandra Desmond and Chantel Desmond, his niece Aria, Lionel Desmond, Aaliyah Desmond, his grandmother Ardella Desmond, and his sister Kaitlin Desmond.Courtesy of Chantel Desmond

There wasn't a lot of money for extras. Income came primarily from Lionel's grandfather, Wilfred Desmond, who drove a bus for work, and Brenda, who was a seasonal traffic flagger.

Although Lionel was known as a jokester, his childhood wasn't always happy. He struggled in school and described his early years as difficult in the National Defence psychiatric assessment. "He experienced severe physical and verbal abuse," wrote Dr. Joshi. Lionel's sister Chantel and his aunt, Sandra Greencorn, suggest that Lionel was referring to schoolyard bullying. Kids stole his lunch and money, they said, and he was taunted for his small size and called "gay."

Lionel met Shanna in high school. When she was in Grade 10, her family moved from Scarborough, Ont., back to their ancestral home in Nova Scotia, across the road from Thelma's mother – Shanna's grandmother – and next door to Thelma's sister.

The couple got to know each other during the half-hour bus ride to and from school. Despite a two-year age gap, they sat together chatting and giggling every day. At school he carried her book bag.

Before long, he grew tight with her family. When Thelma was hospitalized for three months in 2002, Lionel helped Shanna run the home. He jogged the seven kilometres to the Bordens' trailer on the hill to spend time with her and chip in, stacking wood, mopping floors and doing the dishes. Thelma said her family joked that they would have to stop feeding him or he would never go home.

After Shanna graduated, she and Lionel moved to Halifax so that she could go to hairdressing school while he worked odd jobs in construction. In 2004, they moved back to Upper Big Tracadie, where Shanna worked in her mom's hair salon. Determined to start a career, and influenced by a great-uncle who had served, Lionel enlisted in the military. "He was excited to get out," said Shanna's sister, Shonda Borden. "He wanted to get out of the community. So having nothing to do here and no money for schooling … this was the fastest way out."

Shonda Borden sits at the kitchen table in her aunt Sarah MacEachern’s home in Monastery, N.S.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

Lionel Desmond’s half-aunt Sandra Greencorn and half-uncle Allan Desmond sit beside a photo of Lionel.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

Wilfred Desmond, Lionel Desmond’s grandfather, composes himself in the family home in Lincolnville, N.S. Framed on the wall behind him is Lionel Desmond’s Canadian Oath of Allegiance for military service.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

Upset and worried about his future

The Canadian Forces launched the Joint Personnel Support Unit (JPSU) at the height of the Afghan war in 2008 to help ill and injured soldiers, including those with PTSD, get back to work or transition to civilian life. The unit's 24 personnel-support centres and eight satellite offices, located at bases and wings across the country, offer programs and administrative support to those who haven't been able to work for six months.

Lionel was posted to Gagetown's JPSU unit in June, 2014, after his pipe-and-drum platoon commander noticed a change in his demeanour.

"He just wasn't the regular Dezzy that we all loved to hang around with," said retired warrant officer Colin Smith. He still kept a smile on his face and did his work, but became moodier and more despondent over time, said Mr. Smith. "It was really hard for him to express himself … he'd just be sitting there with a blank stare because he was overwhelmed."

Lionel was sent to the Gagetown base health centre, where a medical doctor determined he should be slated for release from the military through the JPSU. Lionel's commanding officer agreed.

But when Lionel found out about the move, he wasn't happy. He was upset and worried about his future, said retired sergeant Jim Butler, who was a veterans care co-ordinator on base at the time. "I know that he truly loved his daughter," said Mr. Butler. "He talked about her all the time. He was a very gentle person, very calm, not too excitable, wore his heart on his sleeve type guy."

Just before he was sent to the JPSU, Lionel confided in Sgt. Butler that he wanted to die: "He said, 'I don't want to be here any more. I can't deal with it. I can't do it any more.'"

Sgt. Butler told his chain of command, as well as the battalion padre and mental-health officials, that Lionel was thinking about suicide. He said he worried that the transfer to the JPSU unit would make Lionel feel even more isolated.

"The staff there are not equipped to deal with mental illnesses. They're not trained to deal with mental illnesses. All it is, is a holding unit to get rid of soldiers that are not medically fit so that they can put medically fit soldiers in their place," Mr. Butler told The Globe and Mail.

Soldiers posted to the JPSU report to a platoon commander, who drafts a transition plan designed to get them back to work. Those who are physically able to perform a job are placed in an employment-placement training program paid for by the military.

Lionel was sent for work-placement training to a nearby garage, to learn how to become a diesel mechanic for heavy-duty transport trucks. But he struggled in the job. "There were too many flashbacks and too many images that used to pop in his head and he couldn't focus on the apprenticeship training," said Lionel's friend, Mr. Trotter.

A military review laid out serious flaws, across the country, with the JPSU in 2015, concluding that it has too few staff and resources to work properly – long-standing issues that had been raised in previous investigations of the unit. The review also expressed concerns about soldiers feeling isolated and alone, and in some cases, taking their own lives.

The Globe and Mail's Unremembered investigation told the stories of some of these men, and documented an ever-increasing tally of soldiers and vets who have killed themselves after serving in the war in Afghanistan, Canada's longest military operation. More than 70 suicides have been reported to date, although the actual number is likely higher, since the federal government doesn't regularly track veteran suicides and has incomplete records on reservists, who made up more than one-quarter of Canadian troops in Afghanistan.

Barry Westholm, a former master warrant officer and sergeant major for the JPSU in Eastern Ontario, believed that the JPSU wasn't providing enough support to soldiers and resigned in protest from his post in 2013. "They're poorly prepared to function in civilian society," he said. "Nobody checks up on them, and you end up with a bunch of isolated warriors, very lethal people out on the streets with the mindset of battle and the skills to function in that environment."

At the time Lionel went to the JPSU, Mr. Butler said, there were only two section commanders looking after 60 to 100 people administratively at Gagetown, and neither was trained to deal with mental illness. Mr. Westholm cited 15 to 20 as a reasonable workload.

A National Defence spokesperson said that all staff positions were filled at the JPSU in Gagetown when Lionel was posted there, and he was supervised by the same section commander. In other parts of the country, however, the JPSU was chronically understaffed, a situation that appears to have continued. (In December, 2016, for example, the Joint Personnel Support Unit was short 73 staff members – or about 17 per cent of its work force.)

A National Defence spokeswoman says changes are coming to the JPSU that will provide more support to soldiers and make their transition to civilian life more seamless. Hiring will begin this summer to fill vacant positions, she said, and more experts will be employed over the next year and a half.

Lionel remained in the JPSU for a year. Then, on July 16, 2015, he was released from the military and began a new life as a civilian.

Family members soon began to notice signs of Lionel Desmond’s instability after his return to Canada. He began to express suicidal thoughts within months of being released from military service.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

A suicide text, and a firearm licence

Four months later, Lionel had no job and was thinking about suicide. According to a subsequent New Brunswick medical assessment for a reapplication of his firearm licence, obtained by The Globe and Mail, Shanna called police on Nov. 27, after he sent her text messages saying he was on his way to shoot himself in the garage of their Oromocto West townhouse, where his guns were stored. "He told her to say goodbye to their daughter and he would see her in heaven," the document explained under "reason for assessment." Lionel was driven to the hospital and seen by a doctor.

"Our client met with [police] and said he did not have any intention of hurting himself, but that he is very depressed, he is concerned for his well-being," said the assessment.

It's unclear whether Lionel actually intended to carry out the suicide plan he described to his wife over text. Halifax psychologist John Whelan said ex-soldiers dealing with mental-health issues face obstacles when they switch from the military's medical care to the public health-care system. Because they're trained to suppress and compartmentalize emotion, many distrust civilians, he said. "They don't really have a language to be able to communicate to people that they are distressed."

Less than three months after the suicide text, Lionel reapplied and received a firearm licence through New Brunswick's Department of Public Safety after a medical assessment by Fredericton family physician Paul Smith, who determined that he posed no safety risk to himself or others. New Brunswick's area firearms officer Joe Roper also signed the medical assessment for Lionel to possess and purchase firearms.

In an interview, Dr. Smith said that he approved the reapplication because Lionel was stabilized on medical marijuana, upbeat, and looking forward to the future. He said the suicide call to police had been more of a marital-discord issue.

"[A licence] would not be given to someone who was not stable," said Dr. Smith. "Every PTSD soldier has thoughts about suicide, so you have to understand who you're dealing with. These guys, at some stage, all have significant suicidal thinking … They become much more stable with the correct treatments."

The real issue, he said, is how Lionel became unstable over the next 11 months, after he left his care and moved to Nova Scotia.

Lionel's mood swayed between affable and irascible. Any little thing, such as if he thought his wife had loaded the dishwasher wrong, or if he thought people were talking about him, could set off his temper, and he would rant for hours, said family members. Thelma Borden said that Shanna would often try to intervene, telling Lionel that his hollering was scaring their daughter. He often responded by packing a dufflebag – filling it with his belongings, including his will and Veterans Affairs documents – and heading out the back door of the trailer.

"Two days later or the same night he'd be back again," said Mrs. Borden. "He'd say, 'I'm sorry, baby, I'm sorry, baby, my head's going crazy, baby.'"

In summer, 2016, with Shanna's encouragement, Lionel was admitted to a Veterans Affairs Canada-supported inpatient mental-health clinic at Montreal's Ste. Anne's Hospital for a few months. Mrs. Borden said he told one doctor in Montreal that he was homicidal. He also punched a hole in the wall during his stay.

He left the hospital in August with prescriptions for pills and more medical marijuana, and seemed fine for the first few weeks.

But then he began to unravel. He posted rants on Facebook, where he went by "Lionel Demon." In one, he claimed that his marriage was over and threatened to go after his wife for financial fraud. In another post, he asked for forgiveness and apologized for swearing and for his jealous, controlling behaviour.

Shanna's sister, Shonda, said Lionel seemed to feel a degree of shame. It bothered him that he was no longer the main breadwinner. "She didn't really need him," said Shonda. "I think that affected him, too, 'cause he wanted to take care of her."

There were other strange behaviours family members noticed, too: Lionel doubted his wife was at her new job as a registered nurse at the hospital in Antigonish when she said she was, said Mrs. Borden. He no longer reined in the bluster and expletives around his own mother, a marked departure from past behaviour.

That fall, Lionel also had some good days. He took part in the 22 Push Up Challenge, a national campaign to raise awareness of suicide rates among military personnel, veterans and first responders. He recorded and posted videos on social media of himself doing the pushups as Aaliyah counted down. And the couple still did things as a family, posing for a holiday photo in co-ordinating grey and red sweaters, and travelling to Halifax to see a movie.

The holiday photo, taken in December, 2016, weeks before the killings took place.Facebook / courtesy of Shonda Borden

But a psychiatrist at St. Martha's Regional Hospital in Antigonish, who saw him at least once, documented issues Lionel was facing in a letter that appears to have been written to help him access additional benefits from Veterans Affairs. "Mr. Desmond has severe problems with PTSD and post-concussion disorder," Dr. Ian Slayter wrote. "He would benefit from regular participation in a gym and in yoga but needs financial assistance to afford them." Dr. Slayter declined to speak about Lionel to The Globe and Mail, citing confidentiality.

The last communication Shonda Borden received from her brother-in-law was a text on Dec. 17, 2016. He sounded hopeful: He'd been to a doctor and was going to go for neurofeedback, a PTSD treatment used to retrain the brain to move out of a vigilante state. (It's not known whether he ever received the treatment.)

His sister-in-law said he also alluded to head injuries he'd suffered in the military: when an LAV he was in rolled during a training exercise in 2005; when he fell off a wall in Afghanistan; and another time he had hit his head on a plane during parachute training in 2008. Although his medical assessment by Dr. Joshi in 2011 cited no head injuries, Lionel blamed his jealousy on concussions that were making his dreams feel real, and said in a text-message exchange with Shonda, "I need to retrain my brain it's terrible. … I need to manage it. … hope for the best …"

By December, however, that hope seemed to have disappeared.

Lionel's sister Chantel said she saw her brother at the end of that month, and he was low. "I felt like he felt there was no cure, and no one cared."

‘He came in the house and – boom-boom – he got her,’ Thelma Borden says of her son-in-law’s deadly shooting.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

After a visit to the ER, a fateful trip home

On New Year's Eve, Lionel and Shanna took Aaliyah horseback riding and to a lobster dinner at an aunt's cabin in the woods. Lionel was jovial, and joked around as relatives played acoustic guitars and set off firecrackers. On the way home, as Lionel drove his wife's new red Dodge pickup truck out the narrow, snow-covered driveway, he accidentally put one wheel in the ditch. "It was minor," said Shonda Borden, who heard about the incident in a phone call with her sister. "Someone that doesn't have PTSD would be like, 'Okay, fine. It's not a big deal,' but that triggered him so bad that he lost it." No one slept in the trailer on the hill that night, as Lionel paced the basement stairs, cursing and hollering, banging counters and slamming doors.

Thelma Borden said she told her daughter to treat Lionel with kid gloves, because he was so depressed and had been through so much, but Shanna was fed up. "She was tired of him hollering and screaming," said Ms. Borden. "She said, 'You have to get help.'"

Thelma Borden says she feels sick now about the son-in-law she thought of as one of her own. “Because he just didn’t snap one day and shoot them. He planned it right to a T.’Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

On New Year's Day, Lionel drove to the emergency room of St. Martha's and reportedly said, "Don't let me leave." He spent the night in the waiting room on a cot, hoping for treatment, but left the next morning. Although he had seen a psychiatrist at least once before at the same hospital, he told family members that he wasn't admitted because staff didn't have his medical file.

Later that day, he drained his and Shanna's joint bank account and stopped at an outdoor sports store, where he bought a consigned SKS, a vintage semi-automatic Soviet military rifle and two boxes of bullets.

At some point that afternoon, Lionel went into stealth mode. He parked up a nearby logging road, armed with two rifles, and stalked through the woods to the trailer on the hill. It was around sunset when he slashed the tires of his wife's truck and used a key, taken from his father-in-law's truck parked outside, to unlock the door.

Shanna was at the island in the kitchen.

"He came in the house and – boom-boom – he got her," said Mrs. Borden.

Chantel Desmond arrived to pick up Aaliyah around 6 p.m., saw the keys in the door and peered in the window. "Shanna was the first person I saw," she said. "I thought maybe she had fell or hurt herself – like you don't think this type of stuff."

"And I looked in and said, 'Oh my God,' and then I went into shock, running outside. … It felt like time was slow. I just remember being on my knees out on that gravel, screaming."

A tattered Canadian flag flies at half-mast for the combined funerals of Lionel Desmond and his mother, Brenda Desmond, at St. Peter’s Church on Jan. 11, 2017. The flag-draped casket carrying Lionel Desmond is removed from the hearse and carried into the church.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

Unanswered questions

Days after the triple-murder-suicide, the federal government offered to pay for all four of the Desmond funerals – Lionel's, Shanna's, Aaliyah's and Brenda's – in an unprecedented step. It also covered the transportation for dozens of family members to the funerals and provided a grief counsellor at the local Legion. (Shonda Borden and Chantel Desmond also started an online fundraising campaign.)

But despite the many unanswered questions surrounding the tragedy, government officials have not called for a military board of inquiry (an internal, non-judicial fact-finding investigation to look into a serious injury or death, including suicide, that occurs outside of action). Such an inquiry has been conducted in many other cases where soldiers have taken their own lives, including Robert Giblin, who served two tours in Afghanistan and suffered from PTSD. He stabbed his pregnant wife multiple times before throwing her off a Toronto high-rise apartment balcony. He also fell from the balcony. A National Defence spokesperson said that a board of inquiry was called because Mr. Giblin was a serving member of the Canadian Armed Forces at the time of his death.

"As Mr. Desmond was not a serving member of the Canadian Armed Forces at the time of his death, there will not be a board of inquiry," said the National Defence Minister's press secretary, Jordan Owens, in a statement.

Of the 54 military board of inquiries held over a two-year span ending in June of 2016, 35 involved suspected suicides.

When Veterans Affairs becomes aware of a vet's suicide, internal reviews routinely take place. However, a spokesman could not confirm whether a review into Lionel's death had taken place, citing the Privacy Act. "The department does consistently look for ways in which they can improve upon its processes and service delivery where permitted by law," said Zoltan Csepregi, a spokesperson with Veterans Affairs Canada.

In Nova Scotia, the Desmond tragedy prompted Premier Stephen McNeil to investigate what health services at St. Martha's Regional Hospital were offered to the former corporal and whether protocols were followed. The confidential review wrapped up in May. Nova Scotia's medical examiner, Matthew Bowes, has yet to make a decision regarding an inquiry. However, he would consider using his rarely exercised power if he concludes the hospital review of Mr. Desmond's treatment was either incomplete or unlikely to bring about changes.

Like many of her family members, Chantel Desmond is livid. "I will fight for my brother and make sure justice comes out of this, as well as accountability, because he couldn't fight for himself," she said.

Similar murder-suicides have occurred in the United States. Carl Castro, an expert in veterans' mental health, who has studied several of these situations, said that while PTSD and failed health-care systems may be contributing elements, there is often no single cause of the violence. "This is really a multidimensional situation. It's why they happen so rarely."

Mr. Castro said that although the Desmond tragedy was clearly a case of domestic violence, it doesn't fit the typical profile, which involves repetitive violence as a way of controlling another person. "Generally speaking, we're not talking about someone who was abusive," he said. "We're talking about someone who, for all practical purposes, had problems themselves, and then in the final act, killed family members and then themselves."

Halifax psychologist John Whelan offered up a different theory on why Lionel did what he did. He said it's possible that ex-soldiers dealing with severe PTSD – if they're highly agitated and feel like they're losing control – can disassociate and get into near-psychotic states. "Any significant anxiety disorder or depression can have an event that puts someone over the edge, especially if there are these kinds of fantastical or paranoid things going on in the background," he said. "You add enough stress here and people can … [have] a brief psychotic episode – for no reason, a person is completely out of their usual state."

‘It’s like, bang, right in your face,’ Thelma Borden says of the Oromocto billboard which she believed featured a photo of her son-in-law’s face.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

A plea that listening begin

Thelma Borden's initial shock at the murders that have destroyed her family is now coiled into a knot of anger – a knot that tightened when she drove four-and-a-half hours to Oromocto to clean out Shanna and Lionel's storage locker near the base. On the way, she and her husband passed a billboard on the side of the highway with a National Defence photo that she had heard was Lionel in army combat gear that says "Oromocto: Canada's Model Town."

"It's like, bang, right in your face," said Mrs. Borden. (On May 1, Gillian Mersereau, executive assistant to the mayor of the Town of Oromocto, identified the image as Lionel Desmond, but after publication, said it was in fact another soldier.)

Mrs. Borden now feels sick about her son-in-law, whom she loved like one of her own. "Because he just didn't snap one day and shoot them. He planned it right to a T," she said.

Like many in Lionel's family, she wants to see the institutions that failed Mr. Desmond step up. She said Nova Scotia's health-care system needs to start listening to people crying out for help. She urged the military to call a board of inquiry looking back on what care and treatment were afforded to Mr. Desmond, and to find out why he wasn't more closely followed after his release from Ste. Anne's Hospital in Montreal.

Her voice trails off as she ponders a future without her beloved daughter Shanna, her bubbly grandchild Aaliyah and the sweet smile of Lionel's mother, Brenda Desmond: "It'll never be over for me."

Six months later, the bullet holes are patched, a new floor is installed and the walls freshly painted a new shade of teal. The wall quote is gone.

But painful reminders remain all over the house. The other day she opened the kitchen cupboard and spotted a white ceramic mug that Aaliyah had made for her father. In black lettering, Aaliyah had written: "Don't be angry Daddy – have a cup of tea."

Lindsay Jones is a journalist based in Halifax.