Tim Cook is an historian at the Canadian War Museum and the author of six books on Canada and the First World War. His newest book, The Necessary War: Canadians Fighting the Second World War, will be available Sept. 10, on the 75th anniversary of the start of the Second World War.

Canada’s reasons for going to war on August 4, 1914, can be summed up in five words: because Britain went to war. But the question was how Canadians would respond.

Fifteen years earlier, during the rather disastrous Boer War, the British Empire had issued a desperate call for men to the dominions of Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Only 7,368 Canadians responded. The soldiers were drawn largely from English Canada and the cities. The war was front-page news in the newspapers for some time but had little impact on most Canadians, who went on with their lives untroubled by the overseas battles.

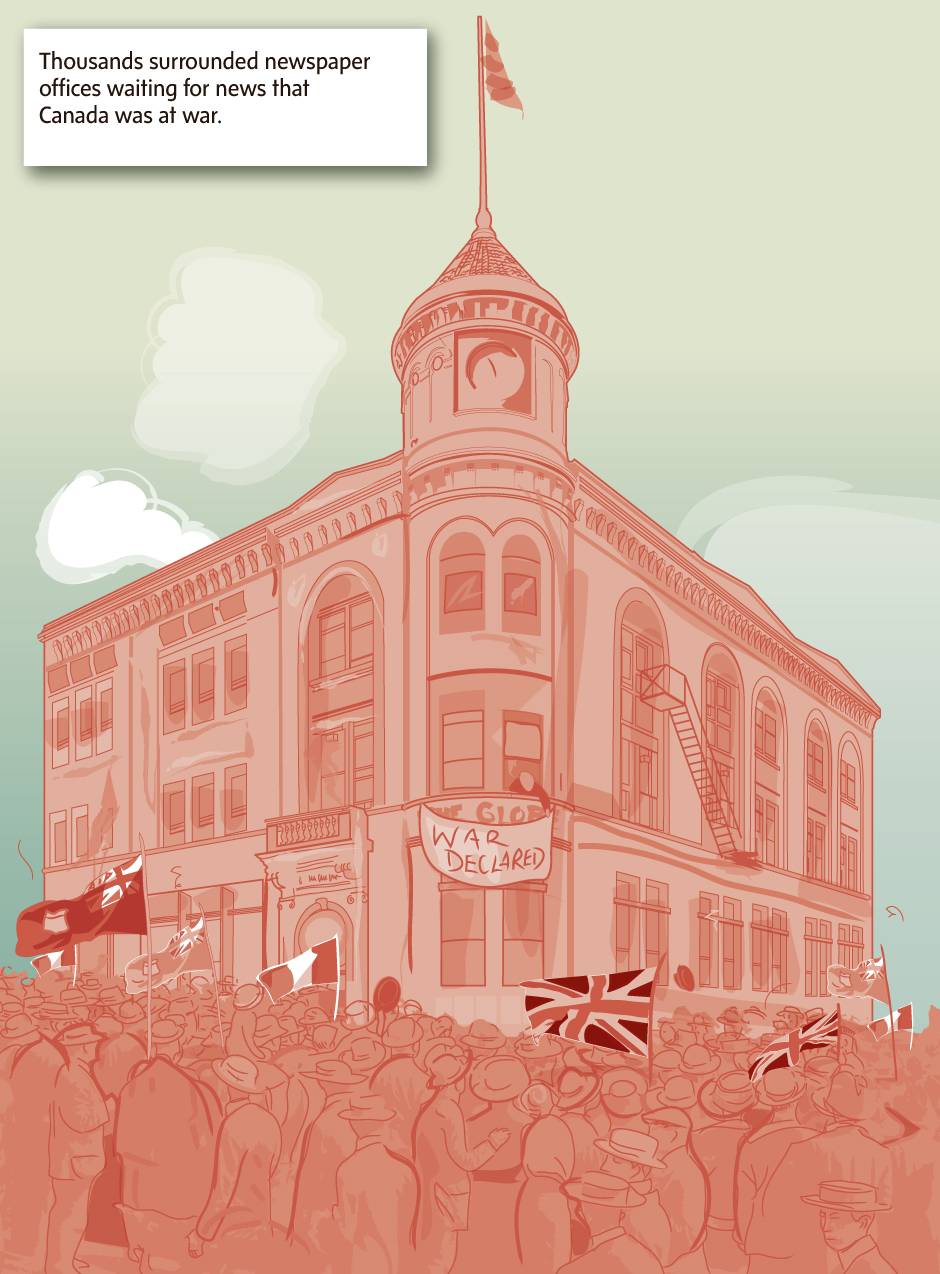

But on that warm day on August 4, 1914, as most Canadians were off work enjoying a long weekend, thousands of men in suits and bowler hats clamoured around newspaper offices in major cities in expectation of war. As breaking news came in from overseas along trans-Atlantic telegraphic wires, often in little more than 140-character bursts, extra-large sheets containing the latest nuggets of information were hung outside newspaper buildings. Crowds grew larger by the hour.

By the time war was declared at 8:55 p.m., there was wild cheering and excitement. Patriotic songs were shouted until throats were hoarse. The Union Jack, Red Ensign and the Tricolor were waved.

Frank Jamieson, then a militia man in the 48th Highlanders of Canada from Toronto, recounted, “I’ll always remember the first night war was declared. The 48th Band came out, played Rule Britannia, and that was the spark that ignited the thing. Away we went in crowds down through the streets. You’d have thought we was coming back from the war, let alone going there.”

Much of this excitement can be attributed to the long build-up of war. But the conflict was also shaping up, unlike the imperial adventure in South Africa 15 years earlier, to be a war in defence of liberal values and for control of Europe. The militaristic Germans, with their Austrian-Hungarian allies, were blamed for starting the war. While historians over the last 100 years have apportioned plenty of blame to Russia, France and Britain, as well as to Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire – all of whom slipped to war through mistakes made, wild hubris, or reckless action – in August 1914 it was Germany’s forces that broke Belgian neutrality as they marched through that nation. Canadians sought to defend Britain, which had gone to war at Belgian’s side, while also believing that the German militarists had to be turned back.

There was also a naiveté regarding how modern nations might fight an industrialized war. While there was much wishful thinking that the war might be over by Christmas, Canadian newspapers throughout July warned of a coming Armageddon. Reporters revealed that the European nations could field million-man armies and were armed with thousands of machine guns and artillery pieces. This seemed to indicate a long and bloody war. But the soon-to-be raised Canadian Expeditionary Force would consist of farmers, clerks, bankers and students, most of whom had never contemplated how to fight a modern, industrialized war.

Ottawa scrambles

Back in Ottawa, there was apprehension as Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden’s Conservative government scrambled to put the country on a war footing. Borden, the dour Haligonian who had defeated Sir Wilfrid Laurier in 1911, knew the dominion was deeply unprepared. It had no air force. It had only two pathetically outdated naval cruisers.

If Canada was to contribute anything to the British war effort, it would be in the form of a land army. Most of the nation’s 3,000 professional soldiers were in a few identifiable and coherent units. The backbone of the Canadian military was the 59,000-strong militia – weekend warriors who marched, drilled and occasionally fired their Canadian-made Ross rifles but rarely practiced fighting together in groups larger than a few hundred.

And the man to bring the new army together was viewed by many as a madman.

Sam Hughes was a long-serving Conservative Member of Parliament who had defended Canada against the Fenian Raids of 1866. Rock-jawed and fierce in gaze, few doubted his martial ardour, but he was a polarizing figure: bombastic and brutal in his verbal attacks, his hatred of Liberals was equalled only by his disgust for Roman Catholics and his bigoted views of French Canadians. The Governor General of the day, the Duke of Connaught, called him a “conceited lunatic.” Many others called him worse.

But as Prime Minister Borden focused on finance and a crucial series of votes in Parliament to pass the War Measures Act – the most powerful legislation to that point in Canadian history – it was Hughes, nearly panting with excitement, who sent 226 telegrams across the country to raise a new army in what he dubbed “a call to arms.” The local militia regiments and military officers were to begin recruiting immediately and bring their new units to Valcartier training camp near Quebec City.

More than a few of the militia colonels double-checked their orders. No one had heard of Valcartier. Indeed, it had not even been built. Still, in the days after war was declared, militia armouries across the country found hundreds of men waiting to enlist. C.E. Longstaff was at one of the armouries on August 5. “They had to have a guard on the main door,” he recalled, “with fixed bayonets to keep the fellows back.”

Some men were moved by the call for King and country. A large number of the first soldiers to enlist, about 60 per cent, were British-born and had close ties to the island kingdom (even by war’s end only half of the soldiers in uniform were Canadian-born). As one of the British-born soldiers remarked years after the war, “I felt I had to go back to England. I was an Englishman, and I thought they might need me.”

Of course, without Canadian passports, all Canadians were members of the British Empire, and English-speaking Canadian-born recruits also felt the irresistible pull to support Britain.

A thirst for adventure drove others into the ranks. “I wanted to see the world and I thought this would be a good opportunity,” remembered R.L. Christopherson. “I didn’t see how else I was going to ever get out of Yorkton, Saskatchewan.”

The lure of the uniform was appealing to all men – and one way to display a virulent militarized masculinity. A bad job or unhappy family life were other motivators. A steady pay cheque of $1.10 a day for privates – about the rate for a unskilled labourer – seemed pretty good to men who had suffered though the economic downturn of 1913 and early 1914. For many soldiers, three steady meals a day in the army was better than anything they might consume in civilian life.

Men enlisted for many reasons, and the only thing that was consistent was that they signed up voluntarily. Although, as militia gunner J.M. MacDonnell recounted, “it seemed not only the natural thing to do but the inevitable thing to do.”

The fight to enlist

With a limited number of spots, the regimental officers could be picky about recruits.

While Canadians were portrayed in idealized 19th-century literature as voyageurs and hunters, bred in igloos and with rifles in hand, most of the initial recruits came from the cities: Their average age was 26, they were about 5’7” and most weighed in under 150 pounds (68 kg). A surprising number of them were missing fingers from industrial accidents.

To ensure each man was suitable for the strain of campaigning overseas, medical officers examined them, prodding and jabbing. Potential recruits who suffered from childhood illnesses and poor nutrition were turned away. Those with shallow chests, hacking coughs and flat feet were denied service. Bad teeth could get you thrown out, too, and more than a few sulking men raged through rotten chompers that they wanted to shoot the Germans, not bite them.

The recruiters also looked for men like themselves – white and Anglo-Saxon. French Canadians had fewer militia units from which to join in the late summer of 1914. While the influential clergy in Quebec at the highest levels supported the war effort, many parish priests actively argued against enlistment. An English army that offered no concessions to unilingual French soldiers did not help matters, although later in 1914 and into the next year several French-Canadian infantry battalions were raised, including the 22nd Battalion, known thereafter as the Van Doos (from the French word for 22: vignt-deux).

Almost all Canadians of colour were denied enlistment at the start of the war. Japanese Canadians, blacks and even a few Sikhs and Hindus tried to enlist and were turned down (although by 1916, as more recruits were needed to fill the ranks, some of the racist restrictions were relaxed).

And only a handful of native peoples were accepted in the late summer of 1914 – although their warrior reputations made them sought after as scouts and snipers. Early recruits included three descendants of Ontario’s Mohawk leader, Joseph Brant, and 23-year-old Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwa from the Parry Island Band who eventually received three medals for gallantry in battle. By the end the war, some 4,000 native people enlisted, often with the belief that they were responding directly to the King of England’s call, as they had done in wars stretching back before Canada’s existence, and that their service would secure more rights within Canada. They were sadly mistaken.

Age was another barrier. New recruits were supposed to be between 18 and 45. Many older soldiers rubbed shoe polish in their hair to fool recruiters. Younger boys, raised on heroic stories of the empire (and before birth certificates were common), claimed an extra few years. By war’s end, at least 20,000 underage soldiers had enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force; a 12-year-old made it to the trenches before he was shot and sent back to Canada to recover.

Those turned down simply kept on trying to enlist. And with no master registry of who had been denied, the young and the old, the sickly and the persistent simply moved on and presented themselves at each newly raised regiment or battery, which were created steadily over the next three years. When the recruits were turned down they went in search of another regiment or unit. Some had to wait several months or even years, but most found their way into the service.

Twenty-three-year-old George Stanley Atkins, who suffered from a curvature of the spine, was an extreme case, but he claimed to have tried to enlist 200 times as he crossed much of Western Canada before finding a place in the 1st Tunnelling Company in November 1915.

But if some recruiters were stringent in applying the rules, others took nearly all who applied in order to fill out their ranks and set off for Valcartier by rail as rapidly as possible so as not to miss the opportunity of going overseas.

One of the new soldiers, Harold Peat, a gawky young man who would be shot in the shoulder and crippled for life in his first battle, wrote of the carnival crowds in Edmonton that saw off his 101st Fusiliers. “Strangely enough, no one was crying. Men and women were cheering; women were waving. Weeping was yet to come.”

A camp comes to life

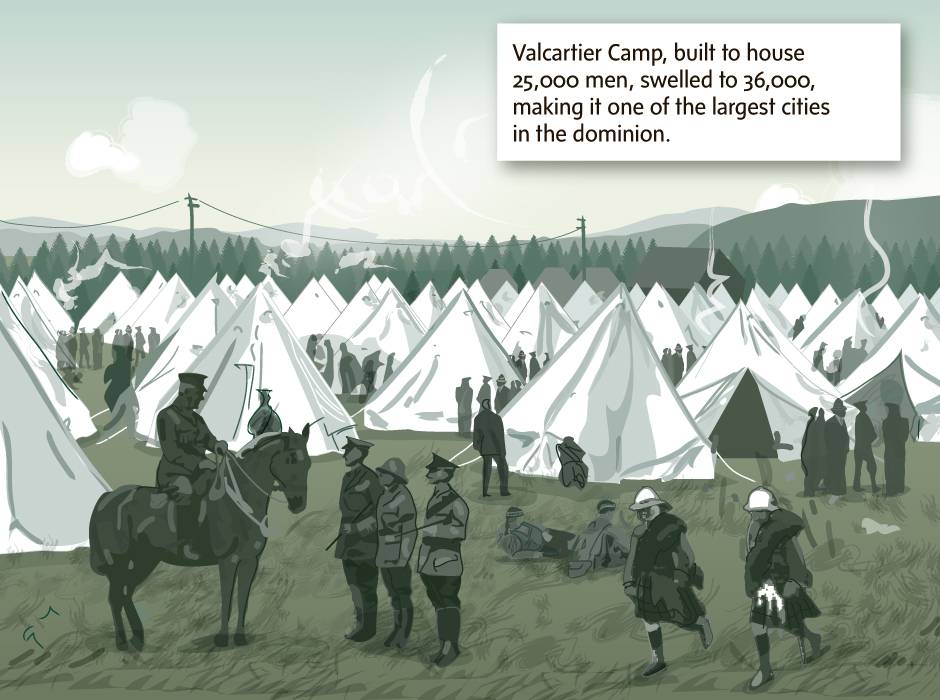

Sam Hughes stood in sawdust to greet his new army at Valcartier Camp, some 25 kilometres north of Quebec City. Hastily hired carpenters and engineers, along with 400 labourers, had cleared dozens of acres of farmland and built a camp to house 25,000 men on the east bank of the Jacques Cartier River. New roads were constructed and electric lights added to the spectacle. A filtration system some 20 kilometres long pumped water into the camp and waste into the river. Hughes’s critics, and there were many, bit back their visceral dislike for the minister and were impressed at how rapidly the camp had been erected, even though the costs were hidden in dodgy departmental accounting.

Beginning on August 18, thousands of Canadians arrived daily by specially-built rail, many having travelled across the country for the first time in their lives. Others hired taxis, rode in on horses and even walked in from Quebec City.

The camp soon swelled to a massive tent city of some 36,000, making it one of the largest cities in the dominion. Units were broken up, combined and then pulled apart again. Officers and the rank and file stumbled around the huge grounds looking for units, many of which no longer existed.

Fred Fish, an 18-year-old artilleryman, ran into his brother who had enlisted in another formation. They hugged one another and swapped stories only to see, in Mr. Fish’s words, “a distinguished-looking gentleman walking along in civvies, carrying a suitcase, and I said to Colin my brother, ‘That looks like old Dad.’ He said, ‘Yes.’ And sure enough it was my father.”

Uniforms were issued – of which there were only two sizes, too big and too small. Men traded and sorted them, all proud of their khaki serge tunics and matching trousers, and peaked caps with maple-leaf badges. The boots, hastily manufactured by good Conservative contractors that Hughes personally selected, soon dissolved in the mud.

There were not enough rifles for everyone but Hughes crowed about creating the longest firing range in the world, with over 1,500 targets. With about half of the new soldiers having identifiable military experience in the militia or the British army, they took easily to the marksmanship. There was also the privately raised Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, which consisted of a high number of former British soldiers and Canadian veterans of the South African War.

Hughes claimed to the throngs of journalists in the camp that his boys were an army of sharpshooters that might single-handedly defeat the Germans. When they weren’t shooting, they went on long marches to harden them. Bayonet practice was a daily event. Soldiers were ordered to yell out vicious sayings as they drove the Ross rifle’s 10-inch bayonet blade into sacks of hay over and over again. More than a few men shuddered at the thought of killing face to face.

And as they trained, there was Hughes – barking orders and ridiculing new officers who had trouble instructing their men in basic military discipline and marching. One of the most respected Canadians to serve, the poet F.G. Scott, later the senior chaplain of the 1st Canadian Division, wrote of him, “His personality and despotic rule hung like a dark shadow over the camp.”

With the camp bursting at 36,000, there was another round of weeding out the undesirables. A small number of wives caught up to their deserting husbands and demanded they be released. They were. Another 3,000 disappointed men were sent home for medical reasons, and some 2,000 more were removed for discipline issues – drinking problems and other unsavoury actions. It took time to train civilians to become soldiers, and many men bristled at being ordered about. Those that could not adapt were out.

But eventually about 31,000 men were attested into the new Canadian Expeditionary Force, signing up for the duration of the war. Excitement carried them forward. In hundreds of large canvas bell tents, the new soldiers filled their nights with tomfoolery, pranks and boisterous songs. A few portable gramophones were brought into the camp but most often the men sang along to mouth organs. Popular songs like I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now were mixed with new favourites like Tipperary. To enliven the nights, men that smuggled in liquor shared it around to their new mates, although Hughes, a devoted teetotaller, urged the military police to ferret out the booze. Most new soldiers had to be content with the runny stew and fresh bread that was served in huge mess areas, and in gulping back chlorinated water.

When the government struggled to find enough ships to transport the new army overseas, men began to grumble and grouse. The black flies tormented them. Weeks of dust and heat, of sweaty and stinking men, wore away at the enthusiasm.

A group of soldiers, angry that a theatre set up at the camp played the same movie several nights in a row, burned it down. The charred ruins were a reminder that soldiers needed to be kept busy.

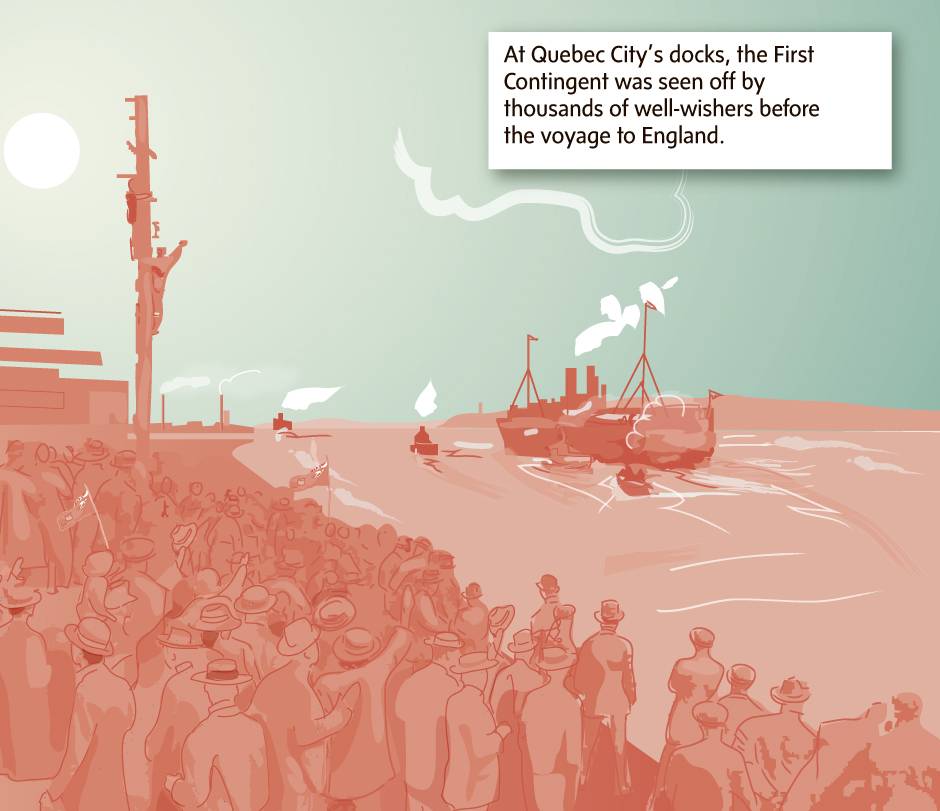

Finally, at the end of September, Sam Hughes’s new army marched to the docks at Quebec City, where they were seen off by thousands of well-wishers. Lieutenant Ian Sinclair later wrote, “Cheer after cheer kept coming from the crowded shore and we on the ships answered with one long continuous cheer and songs innumerable. If they live to be a thousand years, there wasn’t a man on board that night that will ever forget the impression it made on him.”

Transported on 30 luxury liners painted wartime grey, the First Contingent was the single largest movement of Canadians at one time in the nation’s history. They set sail for England on October 3, picking up a ship of 537 Newfoundland soldiers, representing that independent British dominion, and crossed the Atlantic under Royal Navy escort that watched for German U-boats.

Eleven days later, the convoy arrived in Plymouth. The Morning Post wrote of the Canadian contingent: “They will soon be of great value in the fighting line ... But they are also of great value to the empire because they are the symbol of its unity and potential strength.” Following behind the First Contingent came hundreds of thousands of additional Canadians to serve King and country.

Most did not return

The Canadians hoped to go straight to the Western Front. Instead, they trained in England until February before being sent to the trenches, with the Newfoundlanders waiting even longer before being shipped out to the Gallipoli front in the war against Turkey.

They were lucky to miss the battles of 1914, in which hundreds of thousands of French, British, Belgian and German soldiers were cut down by machine guns and shellfire. The Western Front was a mass of mud and a horror of unburied bodies. In February 1915, the Canadians arrived at the trenches and soon faced enemy snipers and shells. There were 278 men killed and wounded in the first six weeks – and few Canadians had even fired a shot at the enemy. To put one’s head above the trench was to invite a bullet in the face. Around the filthy soliders, the corpse-fattened rats and lice plagued everyone.

Most of the First Contingent soldiers, the longest serving of Canada’s 620,000 enlisted men, did not escape the war unwounded or live to see the last day. Battles like Second Ypres, St. Eloi, Mount Sorrel, the Somme, Vimy Ridge, Hill 70, Passchendaele, the Hundred Days campaign and all the smaller engagements and attritional trench warfare between them, steadily wore down their numbers.

Hughes was fired by Borden in late 1916 for a mounting list of scandals and incompetent decisions.

By war’s end, some 60,000 Canadians were killed, and at least 6,000 more died of wounds or illness in the war’s immediate aftermath. That first cold and dark Armistice Day on Nov. 11, 1919, later renamed Remembrance Day, was held a long way from the boisterous summer of 1914.