There's a new kind of road coming to Toronto. A road that uses the space differently, recognizing that it has to do more than just move cars. One that is "beautiful and vibrant" and puts safety first – a crucial move in a city struggling with a rising tide of pedestrian deaths.

They're called "complete streets," and while elements of their planning philosophy have already shown up in Toronto, they have never been formalized into an urban design goal. Next week, city staffers plan to pick a handful of streets to redesign under the new guidelines as pilot projects that they hope will be the start of a decades-long remaking of the city.

"We know designing our streets differently saves lives," chief planner Jennifer Keesmaat says. "The question is: Are we prepared to tolerate, are we prepared to live in a city where preventable deaths are not prevented?"

The scale of this change would be difficult to overstate. In North America, cars have enjoyed primacy for decades, while pedestrians and cyclists were left with crumbs. But the tide is turning.

In New York, Chicago and Washington, D.C., among other places, there's a growing sense that the public right-of-way – the space from building front across to building front – is among a city's most valuable assets. And sharing that space in new ways can bring big benefits to the city. When New York turned Times Square into a pedestrian plaza, climbing commercial rents showed the growing desirability of the area. The Square also made its first appearance on a ranking of the world's top-10 retail districts.

A draft internal copy of Toronto's new complete-streets guidelines lays out dozens of ways to make changes to this city's roadways. They specify that the safety of vulnerable road users has to be considered "at every stage." Noting that people hit by faster vehicles are much more likely to be killed, the guidelines call for speeds to be rethought with safety in mind.

But the approach goes far beyond speed. And there is no blanket approach to remaking the city's varied roadways, with 17 different types of streets identified and options for each kind detailed.

On a street such as Queen, possibilities include broader sidewalks, prioritizing pedestrians and cyclists, and designing the road for "slower but consistent vehicle travel speeds." Some smaller residential streets might become shared spaces, where pedestrians mingle with cars moving at a walking pace and children can play safely in the street.

The urgent need to think differently has been highlighted by a spate of pedestrian fatalities. A 63-year-old woman was run down by a van Thursday evening in Scarborough, pushing the death toll so far in 2016 to 41, more than any full year since 2003.

Fatal crossings: Where and how pedestrians die in Toronto

The number of pedestrian deaths in Toronto has leapt 15 per cent over the past five years – and yet public attention and political reaction continue to fall short. Oliver Moore and Michael Pereira analyzed five years of data and found an increasingly urgent public safety matter

Read the articleA key goal of the guidelines is to make the streets less dangerous. In that sense, they fill a void in the road-safety plan released this summer. That plan contained a range of measures but relatively little focus on actually redesigning city streets to make collisions less likely.

"Slapping up a sign … is not going to work; the competition for the space is too great and we're seeing increased desire to use that space in different kinds of ways," said Maureen Coyle, who sits on the steering committee of the advocacy group Walk Toronto.

"So, instead of saying, 'Let's clamp down, let's punish after the fact,' let's engineer the space so [a collision] can't happen, or when it does happen, let's mitigate the effects."

This will not be cheap. But even more than the cost – every street needs different tactics, so it's not clear how much money would be needed – building new types of streets will require a dose of political courage. Those who emphasize the need to move vehicles quickly would have to accept the greater value of public safety.

Another key goal is to make streets desirable in and of themselves. For streets that are conduits, ways to get somewhere else, this could involve improving the aesthetics. But the goal is also to help streets be destinations, places where people want to shop, eat and socialize.

Properly designed, streets can help foster the so-called third places – the cafés, pubs, barbershops and other places where people pass time when not at work or home.

"Most people do walk to their third places, and government actually can work hard to improve the walk appeal of a place," Florida-based architect and blogger Steve Mouzon says. "The time has come that we need to start thinking about doing places that have great walk appeal, not just places you're merely able to walk. And so the more you can enhance the walk appeal … the more people will get out and walk, and the more vibrant everything becomes in that area."

Toronto's new street guidelines have been three years in the making, with input from multiple agencies, and they still are not finalized. As they roll out, the hope is that the pilot projects will show success and lead to a groundswell of support for this kind of change.

It could happen. Former New York City transportation commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan saw how quickly people took to such improvements under her tenure.

"Projects that alter streetscapes upset people who naturally cling to stability, even if that stability is unsafe or inefficient," she wrote in her memoir, Street Fight. "The flip side is that once change is in place, it becomes the new norm and frames expectations of citizens."

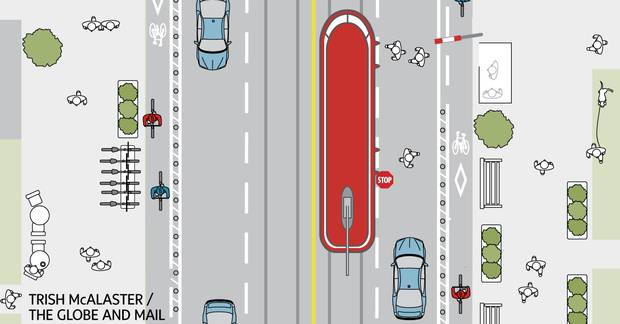

How the 'complete street' works

A complete street is one "that works well for anybody, no matter how you get around," says Nancy Smith Lea, director of the Toronto Centre for Active Transportation (TCAT). Since 2010, the group has spearheaded an initiative called Complete Streets for Canada, working with cities on road design and making available research that shows how to engineer them differently. In this changing world, Toronto's new guidelines may become another important resource. "What we hope will happen is that this will become kind of a widespread document that then other municipalities can use as well," Ms. Smith Lea says. Here are some of roads that have been redone and are profiled on the group's website.

Before.

After.

Davenport Road, Waterloo

This four-lane road averaged 16 collisions a year from 2004 to 2008, according to TCAT, and most people drove at more than 70 kilometres an hour. A makeover added a painted bike lane and a median (which sometimes gave way to a turn lane), while cutting in half the space for auto traffic. Greenery was added, transit shelters were improved and a pedestrian crossing was made safer. The result? Average vehicle speeds dropped and the number of collisions was cut by one-quarter.

Before.

After.

Highway 7 East, Markham and Richmond Hill

Once thought of as the de facto line between the city and country, this road had a design that lived up to the name "highway." The speed limit was 80 kilometres an hour and there were 250 to 350 collisions a year, TCAT says. The most visible change, which was years in the making, are the dedicated lanes for buses along the centre of the road. Also reflecting the urbanizing trend in the area are the painted bike lanes and a reduction in the speed limit to 60 km/h. Collisions dropped to around 100 and pedestrian use rose. Transit ridership climbed 10 per cent and commute times for straphangers dropped by 30 per cent.