Fittingly, the history of the Gardiner Expressway began with a traffic jam. On the day the first section opened in August, 1958, Ron Haggart of The Globe and Mail found motorists crowding to get onto the new escape route from the city. With the official opening still an hour away, “a lone traffic policeman hopped back and forth keeping the early afternoon press of cars away from this six lanes of easy, undulating asphalt ribbon.”

Sam Cass, the city’s traffic commissioner back then, says that in a booming post-war era, Toronto embraced the sleek new roadway. “People thought it was the best thing that ever happened,” recalls Mr. Cass, now 92. “The war was over, the demand was there, the growth was there – it was the right thing to do.”

Half a century later, the Gardiner has become one of Toronto’s worst headaches. Environmentalists consider it an outdated monument to the tyranny of the automobile. Enlightened urban thinkers call it an eyesore that stands in the way of a waterfront renaissance. The highway is so decrepit that chunks of concrete routinely drop off its crumbling mass, threatening those below.

What to do with the cursed thing – patch it up, tear it down, bury it, cover it with a roof? – has bedeviled a generation of local politicians. That debate is heating up again as city council gets ready to decide whether to adapt or remove its eastern stretch.

Still, looking back, it is hard not to admire the energy and ambition that gave life to this hulking creature. In the 1950s, Toronto needed a way to deal with its crushing rush-hour traffic. It got a massive elevated roadway sweeping from one side of the city to the other. Today, when governments are trying to push ahead with a badly needed new round of city building – from redevelopment of the Port Lands to renewal of public housing to an overdue transit build-out and dealing with the Gardiner itself – there is something to be learned from that feat of will, that exercise of raw political power.

THE FINAL STRETCH

This month, city council is set to decide how the future of the eastern Gardiner – and Toronto’s waterfront – will look. This is a series examining the city's most contentious highway. Find more stories, videos and photos, past and present, all series long here or at tgam.ca/thegardiner.

>>Last update: Toronto chief planner at odds with mayor over eastern Gardiner removal

>>Alex Bozikovic on why the Gardiner must come down.

>>Marcus Gee on the optimistic early history of the Gardiner and its namesake: Frederick “Big Daddy” Gardiner

>>Elizabeth Church on how the Gardiner was the artery that connected her family.

>>Oliver Moore looks abroad to see how others have handled life with an elevated expressway.

>>Globe Debate: Dear Toronto: Tackling the Gardiner would be world-class

>>Before and after: An interactive look at the Gardiner's past and present

>>Video: The Gardiner in motion.

The expressway was the creation of one man above all: Frederick Goldwin Gardiner, the cigar-chomping, whisky-drinking force of nature who was the unchallenged strongman of Toronto politics in his day.

His biographer, Timothy Colton, called him a tyrant and a charmer, “big in size, big in ambition, big in appetites and big in rhetoric.” His nickname was “Big Daddy.” Editorial cartoonists depicted him as an ermine-clad emperor or, in one famous rendering by the Toronto Star’s Duncan Macpherson, the “Maharajah of Metrostan.”

The son of an Irish immigrant who made his living as a prison guard and later landlord, Mr. Gardiner grew up in Toronto’s west end. He won a gold medal at Osgoode Hall law school, became a successful downtown lawyer and branched out into business. He was an organizer for the Conservative Party and reeve of the village of Forest Hill before it became part of Toronto.

In 1953, when Mr. Gardiner was 58, Conservative Premier Leslie Frost named him chairman of a whole new level of government: Metropolitan Toronto. As its overlord for the next eight years, he turned all his powers toward building the bones of a big city – roads, bridges, subways, sewers, schools, parks and, above all, highways.

At the time, Toronto roads designed for horse carts and trams were being overwhelmed by that dominant new urban animal, the automobile. The Globe reported in 1948 that every day about 105,000 cars were streaming into downtown, known to traffic experts as “suffering acres” because of its congestion. The volume was forecast to rise to 160,000 by 1958. King and Queen streets were choked with traffic. So was the old Lake Shore road.

It seemed obvious that the solution was to build more, better roads. Inner cities were then considered noisy, crowded, dangerous places, unsuited to healthy living. What if people could work in them during the day but retreat at night to quiet, spacious, safe new suburbs. What if, instead of reaching those suburbs by riding on clanking streetcars or driving along poky local roads, they could sail in and out of town on rivers of blacktop?

Los Angeles opened the Ramona Boulevard freeway in 1935, helping to kick off the age of the urban highway.

The idea was enticingly simple. If city roads were getting clogged, then bypass them with new roads where traffic could flow freely, unencumbered by annoying stop signs, traffic lights or pedestrians. In the same way that railways were designed only for trains, these roadways would be designed only for cars. They would travel through, around or even over the existing street grid, with ramps to speed motorists on and off.

As early as 1943, the City of Toronto’s Master Plan called for a new express route along the lakeshore, shown on a map as simply “Superhighway A.” It took Big Daddy to turn a line on a map into a highway in the sky.

Mr. Gardiner was a student of highway engineering and an unabashed fan of big, wide roads, which he argued were essential to knitting together his booming fiefdom. He once said he would cut five or six feet off many sidewalks just to make wider streets. When critics complained he would ruin neighbourhoods, he replied: “There have got to be a few hallways through living rooms if we are going to get our metropolitan arterial system built.”

An impatient Mr. Gardiner won approval for an eight-mile lakeshore highway in 1953 and badgered hesitating councillors into starting construction in 1955.

When politicians wrangled over the route of one section, Mr. Gardiner threatened to halt all construction until they had a deal. When conservationists complained his expressway would plow through historic Fort York, he said he would simply move the thing to the waterfront, “brick by brick.” (Historical societies wouldn’t buy it, and he made one of his few retreats, agreeingto reroute the roadway around the fort.)

As mayor Nathan Phillips once put it, “When he really wanted something, he just came and beat it out of you.”

Bulldozers growled into action – and, as Mr. Gardiner said in 1958, “once you get those bulldozers in the ground, it is pretty hard to get them out.” They levelled the old Sunnyside Amusement Park on the western lakeshore. They levelled the small 19th-century neighbourhood of South Parkdale.

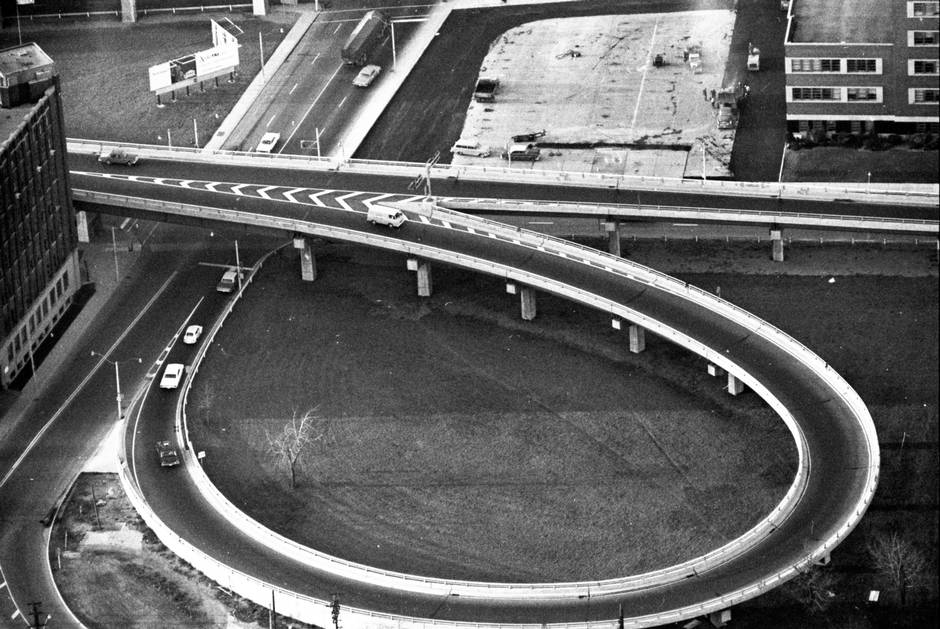

Concrete pillars rose like marching soldiers along the waterfront. Next came the massive beams connecting them. On top of those went steel girders, on top of that a concrete deck, on top of that a layer of asphalt.

The completed structure has 17 ramps. Its deck has an area equivalent to 30 football fields.

By the time the decade-long project was finished in 1966, it had cost about $110-million, or about $800-million in 2015 dollars. That’s a bargain in today’s terms. Just building a light-rail transit line along Finch Avenue West is expected to cost $1.2-billion.

Journalist Pierre Berton even penned a tongue-in-cheek poem about the expressway in the Star: A Lyric Ode to a Supermayor’s Superhighway. “Frederick G. Gardiner Expressway, I love you,” it began. “For you are new and beautiful. And your curves are gentle.”

The Gardiner was not loved for long. Expressways soon went out of fashion. Even as the Gardiner was being finished, community activists were protesting a plan to cut a swath through the neighbourhoods of central Toronto to build the Spadina Expressway. Leading the charge was Jane Jacobs, the American author who moved to Toronto after helping block a similar project (New York’s Lower Manhattan Expressway) championed by a figure just as overbearing as Mr. Gardiner (“master builder” Robert Moses).

They won. Premier William Davis stopped the Spadina Expressway (now the Allen Road) at Eglinton in 1971 with an utterance that would have been sheer heresy to Mr. Gardiner’s ears: “Cities were built for people and not cars.”

A plan to send a Scarborough expressway from the eastern end of the Gardiner up to join with the 401 collapsed. So did plans to build an extension to the 400 south into the city, an east-west Crosstown expressway and a Richview expressway heading west from Eglinton Avenue. The Gardiner and the Don Valley Parkway (another of Big Daddy’s babies) got in under the wire, and only because neither displaced large numbers of ensconced residents.

As every driver knows, those roadways soon became choked with traffic during peak hours. Toronto was left with a truncated freeway network.

Mr. Cass, the traffic commissioner, now living in North York, thinks Toronto blundered when it throttled back on its expressway expansion plan. “Once they started taking bits and pieces off of the damned thing it no longer had the function it was designed for.” As a result, he says, “Today is just one big jumble of traffic.”

Trying to escape the city to the east along what is often called the Don Valley Parking Lot, it is tempting to wonder if he has a point. Trying to escape via the northwest, you wonder some more as you crawl along Black Creek Drive or try to get onto the Allen.

But the modern vision of the ideal city is very different from Mr. Gardiner’s. Instead of dividing cities into separate rooms for living and working and linking them with asphalt corridors, planners started to talk about integrated live-work-play city where people could walk, bike or take public transit to work. Just such a district is even now rising up just next to the Gardiner – the high-rise district of offices and condominiums known as the South Core.

As urban thinking evolved, the Gardiner started to crumble. The structure’s design contains a fatal flaw. Look at old pictures of those pillars going up during construction and you can see the steel reinforcing bars sticking out the top. Engineers of the time didn’t consider what might happen when road salt is applied to an elevated highway in winter. What happens is that salty water seeps into the concrete. Those steel bars start to rust and, as they do, they expand. The expansion cracks the concrete. Freezing and thawing worsens the cracks and bits of the concrete break off. The technical term for all this is spalling.

Pass beside the structure and you can see the crumbling outside edges of the roadway, known as the parapets. Pass underneath and you can see the parts where workers have patched the crumbled concrete or even shored up the roadway with wood supports, a process called “timbering.” When you are using bits of wood to hold together a behemoth like the Gardiner, you know you are in trouble. Mr. Gardiner would be appalled at the state of his offspring. A recent report by city staff says it is “imperative” to take some kind of action.

Given the chance to turn back time, would Toronto build the Gardiner Expressway? Considering all the expense and bother since its construction, probably not. Interviewed by the Star in 1973, the expressway’s designer, engineer Bill Malone, called it “a monster – I’d never do it again.”

It’s a magnificent monster all the same. Travel on the Gardiner remains a special urban thrill. If you happen to drive it when traffic is moving, you whisk through the heart of the city in minutes, catching glimpses of the harbour on one side and the skyscrapers of the financial district on the other. With the rise of the South Core, tall buildings now crowd around the central span of the roadway. It is like speeding through a glass canyon.

Mr. Gardiner may have been a high-handed, bull-headed beast, a type almost unimaginable in today’s world of focus-grouping politics. But he built his highway, naysayers be damned. As Sam Cass puts it, “Things were done when he was around. He didn’t just gab about them.”

Mr. Gardiner left his post as Metro chairman in 1962, clearing out his office in city hall to return to private business. His health declined. He had surgery for arthritis and an intestinal condition. In 1966, when he posed for photographers before the opening of the Gardiner’s final stage, he was walking with a cane.

In 1967, he suffered a stroke. In his rare interventions on city issues, he came across as a caricature of himself, cranky and out of touch. When conservationists fought to save Old City Hall from the wrecker’s ball, he said: “What’s historical about it? It was only built in 1895. Christ, I was alive in 1895.” Three years later, in 1972, the city elected David Crombie as mayor on a platform of preserving neighbourhoods and stopping expressway construction. Mr. Gardiner’s vision of a city of expressways was long dead when he rode that great bulldozer to the hereafter in 1983, but his confidence in Toronto’s future and his insistence on building the physical foundations for its growth still have something to teach us.

A photograph from 1960 shows Big Daddy walking along an unfinished part of the Gardiner. Fresh, unpainted asphalt lies under his feet. Behind him, the road stretches out into the hazy distance.

He wears a double-breasted suit and black dress shoes. Barrel-chested, stone-faced, he walks toward the camera. There is no doubt on that face. He is getting things done for his city and he wants the whole world to know it.