When the King Street pilot was first envisioned, it was about more than speeding up streetcars. City planners dreamed of transforming the crucial roadway, discouraging drivers in favour of transit and adding dynamic public space that would reshape the corridor.

Instead, the city "shelved" broader plans to improve the look and feel of King Street, nervous that being too radical would bring political and public opposition. The project was launched as a transit initiative that did little to improve what planners call the public realm.

The city then found itself on the defensive as business opposition mounted, forcing staff and politicians to scramble for ways to head off critics and add elements that would bring life to the street.

Observers say the response – including escalating offers of free parking and a restaurant promotion announced, then discarded – could have been avoided if the city had started with more comprehensive changes.

"There are components of the public-realm plan that were sort of shelved, and very clearly those components of the public-realm plan are a critical part of the success," said former chief planner Jennifer Keesmaat, who left the role two months before the project launched.

"I think that there was some fear about taking the pilot too far too quickly, but it's kind of like one of those situations where you can't just dip your toe in the water. You're either in the water or you're out of the water, but you can't be halfway in."

In November, the city eliminated street parking and prohibited continuous vehicle traffic on King Street from Bathurst to Jarvis. Transit ridership is up, but some businesses complain of big drops in customers. Now, after three months, the year-long project is entering a pivotal period.

The worst of winter should end soon, likely bringing more people outside to use the street. The financial district's business improvement area (BIA) has been surveying its members before it takes a public position on the pilot. A coalition of civic and residents' groups has begun promoting King Street.

The popular musical Come From Away returns to a King Street theatre next week, and is expected to draw thousands. Around the same time, the city is planning to release credit card sales data that will help show whether businesses are, in fact, suffering.

The Globe and Mail canvassed more than 140 businesses throughout the pilot area and the responses did not suggest the street is deserted, as some opponents insist. But impacts vary widely. While most respondents said business dropped after the pilot launched, around one-third reported it being flat or improved.

Pedestrians walk along King Street West. In November, the city eliminated street parking and prohibited continuous vehicle traffic from Bathurst to Jarvis.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Life in the curb lane

The King Street pilot was born of the " TOcore" planning exercise to re-imagine how people live in and use the city's downtown. And as the idea of having fewer cars on King took shape, there were plenty of examples for using the space that would be freed up.

When New York prepared to turn Times Square over to pedestrians, the city put out chairs for passers-by. In Australia, a multibillion-dollar light-rail project in Sydney includes prioritizing pedestrians and transit on a key downtown road, with broader sidewalks and places for people to linger.

Cities have created mini-parks in road space, or installed patios, workout areas or art.

Good amenities can attract people even to unlikely spaces, as Toronto showed when it opened a skating venue under the Gardiner Expressway. On King Street, though, high-quality public-realm improvements were absent when the pilot project started.

Three sources at city hall said a transportation improvement alone was seen as easier to get through council, where many were unsure about the project, than changes to make King nicer. Another said this approach was about winning public acceptance.

"The fact that the public realm was not delivered at the same time is acknowledged by everyone to be a mistake, and the city is struggling to catch up," said Ken

Greenberg, the urban designer and principal of Greenberg Consultants, which was not part of the project.

Planters were placed in what had been King's curb lane, and picnic tables were put out only later, by which time the city was in a deep freeze. A design contest on how best to use the new road-space was not launched until January – two months after the pilot began.

"This is actually about city-building, it's about creating a place and a destination right in the heart of the city, and that piece has been stumbling along," Ms. Keesmaat said. "That piece needs to be brought to the fore. It's the piece that, of course, you hear the businesses along the corridor shouting about, and it's the piece that can actually be fixed with some city-building moves."

Even as the pilot began, there were high-level doubts at city hall about whether it would work, a concern that was reflected in the lack of hoopla around the launch.

Dan Gunam, CEO of Calii Love, which has a restaurant in the area, said the city should have gone the other way.

"When they kicked off the pilot, they should have celebrated by having a street festival with the businesses on King, instead of just … [starting] to give tickets to drivers," he said in an e-mail.

'Ghost area'

There's a recognition at city hall that this could have been done better.

"If we were to do this again … it would be in everybody's interest to roll it out in the spring, as opposed to the late fall," said councillor Joe Cressy, whose ward includes the pilot project area. "I think it would be in everybody's interest to roll it out with the public realm improvements … ready to go on Day 1 ."

The city has struggled to fix the situation.

A one-time-only parking discount was offered and then boosted to two hours of free parking, available every day until the pilot ends.

In January, politicians including Mayor John Tory announced plans for a Winterlicious-style dining promotion and short-term street animations, including ice sculptures and fire-performers. The promotion idea was then dropped and sources say it will be replaced by a partnership with the order-ahead app Ritual. The animations were put on hold because of cold and then cancelled when business owners said they wanted more focus on marketing, a city spokesman said.

The project was not helped by launching just before an unusually cold spell of winter. Also, the main theatres on King were on a reduced schedule, compared to the previous year. Even worse, the notion began to spread that King Street was closed to cars.

Some opponents of the project encouraged that perception. Politicians Doug Ford and

Giorgio Mammoliti said cars had been banned. Angry local business owners said King Street was deserted and un-welcoming. Al Carbone, the owner of Kit Kat Italian Bar & Grill put up a large ice sculpture of a middle finger, stressing that it was aimed at the city, not transit riders.

"I think [the city] screwed up when they launched it, because the perception the public had is that it's inaccessible," said Bronwen Clark, owner of Rodney's Oyster House. "I'm hoping the public … realize you can drive down and there's plenty of places to park."

How all these factors combined with the new driving restrictions remains unclear. What is known is that many businesses say the pilot's launch coincided with sharp declines in revenue.

This was reflected in The Globe's research of commercial enterprises along King. More than one-fifth of the businesses participated in a survey or did an interview, although some would do so only anonymously, fearing backlash. Respondents were under no obligation to open their books, making it impossible to verify their responses.

Their data show revenues were down an average of about 13 per cent in December from the previous year, a figure that obscures a substantial amount of variation.

Retailers and service-providers generally did better than restaurants and bars – a sector that typically has tight margins and reported being down an average of 16.7 per cent. Bars and restaurants west of Spadina Avenue did better than those to the east. Those between Spadina and John Street reported the biggest drops, an average of nearly 23 per cent. Dhaba Indian Excellence, a restaurant opposite the TIFF Bell Lightbox, reported the worst results, saying revenues were down 80 per cent.

"It is not a transit project, but rather a bully project to make businesses suffer, residents suffer and tourism suffer," Dhaba executive chef PK Ahluwalia said in an e-mail. "No one wants to be here in the ghost area of the city."

The riders' view

Amid such complaints, the pilot's saving grace has been its transit improvements.

King is already the city's busiest surface transit corridor, and ridership is climbing. The Toronto Transit Commission added larger vehicles when the pilot began and deployed new streetcars there as they arrived. The agency says it is "consistently delivering above our scheduled capacity," although getting aboard remains an issue at the busiest times.

Although average streetcar speeds haven't improved dramatically, many passengers say the changes are saving them meaningful amounts of time, including through shorter waits.

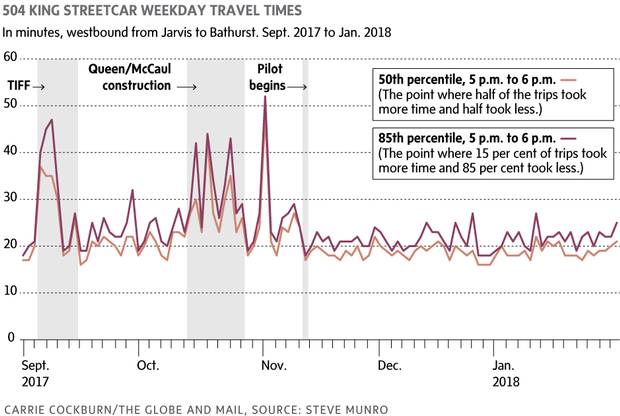

Transit blogger Steve Munro crunched January data for westbound trips in the early evening and found greatly improved reliability. The extreme variations in travel time had vanished, making the streetcar more predictable.

"I've actually started moving from taking the Queen streetcar to taking the King instead, because it moves faster and has a little bit less people on it," said Erin Lambert, who lives around Queen and Bathurst. "From the improvements I've seen as a transit rider, I think it should stay."

Opponents have been shopping around city hall a proposal for a radical roll-back of the pilot. But Mayor Tory on Thursday poured cold water on the idea of relaxing the restrictions.

"We do not believe there is adequate evidence that an evening or weekend exemption would offer any access that is not already available to drivers wishing to reach the King Street area," he wrote in a letter to area stakeholders.

Councillor Cressy, noting that 43 per cent of Toronto's non-residential development is slated for the core, said debate about the pilot must include the broader economic value.

"Being able to ensure that we don't have a financial core for the country that is caught in a constant state of gridlock is about general economic prosperity, and for the city, that prosperity is important," he said

And the stakes are higher than just this area. As the TTC considers how to create priority routes elsewhere, it is looking at King as an example of how to make surface transit work better.

"For more customers to choose transit, it must be faster and more reliable than if they took a car," TTC deputy CEO and chief customer officer Kirsten Watson recently told the agency's board. "We're seeing that right now with the King Street pilot."