Quietly, gently, brutally, Vanessa van der Linden extinguishes hope.

A year ago, Dr. van der Linden, a pediatric neurologist in the northeastern Brazilian city of Recife, found her clinic waiting room full of anxious parents holding babies with abnormally small heads. When she examined the babies' brain scans, she saw crusts of calcium, or pockets of fluid, or blank spots where whole pieces of the brain were missing.

It was Dr. van der Linden, plus her mother and brother, also pediatric neurologists, and a handful of colleagues, who began to trade stories and WhatsApp messages and then to raise an alarm – leading the Brazilian government to start an investigation into the strange new birth defects affecting babies in their area. Weeks later, her family and colleagues would tie the microcephalic babies to the Zika virus, a mosquito-born fever that was previously believed to cause only a mild fever and rash.

A year ago, Dr. van der Linden did not know what to tell parents: no one had seen brain damage like this, caused by this virus, and it was impossible to give a solid prognosis. "We can't take away the hope in the beginning."

But these days, she knows, and it is time that parents begin to accept the reality of what life will be like for their babies.

"It's difficult to talk to parents about a baby so small – but now, with one year, we can make a prognosis. They ask me, 'Will my baby walk?' And I always say to them, 'it's impossible to walk without head control or first sitting up, or interaction. A baby needs first to interact,'" she said, her voice steeled against the sadness of the last year.

She has about 100 patients now, with confirmed Congenital Zika Syndrome, born at the crest of the epidemic last year. Of them, most are severely affected, she said; only 25 can interact at all. Most don't make eye contact, can't sit, have epilepsy, struggle to eat and to grow.

"With time and with the life of their baby, the parents are coming to understand," Dr. van der Linden said.

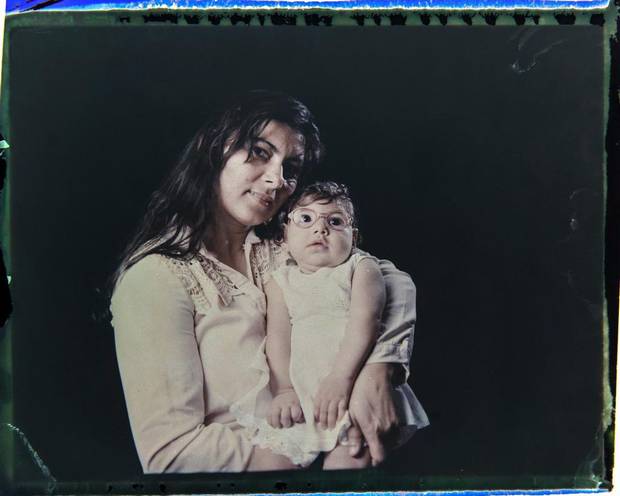

Jusikelly da Silva poses for a photo Sept. 29, 2016 with her daughter Luhandra, who was born with microcephaly, one of many serious medical problems that can be caused by congenital Zika syndrome, in Recife, Pernambuco state, Brazil.

Felipe Dana/AP Photo

In the year of Brazil's Zika emergency, there has been a rush of scientific discovery: microbiologists have sequenced the genome of the virus and traced the path it follows to damage the developing fetal brain. A vaccine is in clinical trials. Entomologists have proven that one mosquito species transmits the virus and are investigating other species that may. Epidemiologists have tracked the spread of the virus up through the Americas, and have begun to monitor and follow infected pregnant women. And this past week, researchers with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control identified five congenital anomalies that appear in a pattern they declared unique to Congenital Zika Syndrome.

"But still we have many questions without answers," said Dr. van der Linden.

The biggest one is this: after that first alarm she and her colleagues raised a year ago, the national Ministry of Health in Brazil, and those in a dozen other countries, were braced for disaster. But it didn't come: the most recent figures from the World Health Organization show 2,175 babies with confirmed congenital Zika Syndrome , and 2,033 of them were born in Brazil, 90 per cent of them in a cluster in the northeast. The phenomenon has not been repeated elsewhere.

"Why just the northeast of Brazil? And how many mothers with Zika infection will have a baby with problems? We don't know this rate," Dr. van der Linden said, listing off the mysteries.

Why do some women who get Zika have healthy babies and others not? At what point in their pregnancy are they most at risk? What other factors may be making them vulnerable? Why are some babies born with the tiny heads, and others at first appear normal? And what other ailments and physical challenges will these babies develop as they grow older? There are no answers to these questions yet.

In the epidemiological division of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, experts are focused on what has made the impact of Zika in one part of the country so unusual and so severe. "We have to think, what could cause that rapid increase in microcephaly in that part of the northeast region?" said Fatima Marinho, co-ordinator of disease surveillance at the ministry in Brasilia. "Was it just the virus or was it a co-factor associated with Zika?"

Virologists and epidemiologists have two main hypotheses. The first is that it's genetic: Something in the genes of these mothers in northeastern Brazil made their babies uniquely vulnerable. The second theory is that Zika has a co-factor, some other element at play, when it causes the fetal damage – that the pregnant woman also gets infected with other mosquito-borne viruses, such as dengue or chikungunya, for example. Early research suggests the women in the northeast have a higher viral load – the amount of Zika in their blood – than women infected elsewhere.

And research is also under way into social determinants and environmental factors – Dr. Marinho points out that the majority of women affected in the northeast cluster are poor, and Afro-descendant. Many live in drought areas. There could be other influencing factors, she said.

Colombia, which has the highest rate of Zika infection outside Brazil, has a registry of some 20,000 pregnant women with the virus, but only 54 babies with the syndrome so far. In part, that's likely because women who contract Zika while pregnant or have a diagnosis of an affected fetus have been choosing to terminate their pregnancies, something they can do in Colombia but cannot in Brazil. But there is a race under way to decipher what else is different between Colombia and Brazil.

Epidemiologists are watching Puerto Rico, where the CDC have registered 28,000 cases of Zika.

Rosana Alves holds her daughter Luana on Sept. 29, 2016 in Recife, Brazil. Alves has three daughters and has left work to take care of Luana, who is equipped with specially designed leg braces to help position her feet.

Felipe Dana/AP Photo

And what will this year bring in Brazil? The peak of Zika infection comes with the summer rains in December, January and February; affected babies would begin to be born around now. Dr. Adriana Melo, a fetal medicine specialist in the northeastern city of Campina Grande who, a year ago, was the first to find Zika virus RNA in amniotic fluid, says she diagnosed an affected baby three weeks ago – it was the first she had seen since last March.

Epidemiologists are predicting fewer Zika cases across Brazil this year – vector-borne viruses such as this one tend to come in "wave" cycles, a bad year every few years, and this year they expect more chikungunya, rather than Zika. Dr. Melo said she also expects there is now greater immunity to Zika in the population of her area – but on the other hand, she worries about mutations in the virus. It was, after all, a mutation in Zika's RNA that turned it into something malignant (and made it sexually transmissible.)

Dr. Marinho said the Ministry of Health has earmarked funds to make 2.3 million new Zika tests available for pregnant women, and will expand its house-by-house inspections for mosquito breeding spots, in an effort to ensure the number of new infections is lower this year.

The CDC findings, published on Nov. 3 in the journal JAMA Pediatrics, say Zika causes some cognitive and motor disabilities that can look like those of other congenital infections, but that the virus also creates a "consistent and unique" pattern of congenital anomalies. These are the five that, appearing together, set CZS apart: severe microcephaly with a partially collapsed skull; scarring of the retina; shortening or hardening of muscles or tendons (such as club feet); excessive muscle tension that restricts movement; and decreased brain tissue, with calcium deposits.

Yet while that list should make it easier to identify some Zika babies at birth, not all will have all of those visible defects. Another outstanding question is how many more "Zika babies" have been born in Brazil but not yet been identified. Dr. van der Linden has new patients, who were only recently referred to her when they failed to reach development milestones: their brain scans look much like those of the children whose mothers had confirmed Zika infection.

"I'm certain that the number of confirmed cases is actually much higher," said Dr. Melo.

She spoke last week at a gathering of international experts on Zika in Rio; many of the scientists there argued that, now that health workers know that they must be alert for more than just microcephaly, and that they must track possible Zika-affected babies for at least two years to spot developmental delays, the number of cases beyond Brazil will likely rise.

Dr. Albert Ko, an epidemiologist with Yale University who has been working on the Brazilian Zika epidemic, told the Rio meeting that microcephaly is "the tip of the iceberg: There are many less obvious but more severe impacts on the fetus."

For Dr. van der Linden, the challenge these days is to try to map the bleak terrain of this new syndrome. As the Zika babies reach their first birthdays, some of the less severely-affected ones can sit without support. "In these ones, it's easier to see the motor control issues," she said. "We don't know yet about the cognitive impact."

Many of the more severely-affected babies are struggling to eat; she recently began referring them to have feeding tubes put in place, in an effort to prevent malnutrition and stunting. "Those ones – we're very worried," she said.

'My job as her mother is to be patient and have hope

'

In February, The Globe introduced readers to Ester Sophia da Silva, born Oct. 10, 2015, in Campina Grande with a normal physical appearance, but later diagnosed with congenital Zika Syndrome.

Ester Sophia does not yet sit up, and cannot guide an object to her mouth. She wears eyeglasses to try to correct an imbalance in her vision. But her hearing is good, which helps in her efforts to try to follow the voices of her family.

"This has been a year of many battles, many struggles, but also many victories and a lot of hope," said her mother, Aldayanne Alves da Silva. But with every victory comes a new challenge, getting Ester Sophia the therapy, the care and the socialization she needs.

"Unfortunately, the doctors still don't have answers for many of the questions we have," she said. "Each day there is something new, and the research centers rely on partnerships between mothers and doctors because it is our account of what happens on a daily basis that helps them understand what is happening." It also helps that more is known about the syndrome, she said; it lessens the stigma and the fear.

In the past nine months, Ms. da Silva has joined an evangelical Christian church, and also met a man she has married. Caring for Ester Sophia is a full-time job, and the baby's father does not contribute, so the support of her new husband is a godsend, she said.

Ms. da Silva, who also has a three-year-old son, said she knows there are many things Ester Sophia should be doing as a child who just turned one, and isn't, but believes she will get there. "She will do things, she is just going to do them at her own pace. My job as her mother is to be patient and have hope, and help her with what she needs." She described Ester Sophia as espertinha – somewhere between clever and devilish. The baby is doted on by her big brother and Ms. Alves' extended family.

For Ms. Avles, and the other mothers of affected babies she knows from their twice-weekly hospital visits, every small development milestone is a cause of "joy and celebration," she said. Then her voice cracked, and she spoke about the anxiety of continuously wondering what her daughter's future will look like.

"It's going to get harder," she said. "But people are going to forget these children. And it's the mothers who are going to have to fight for them."

Stephanie Nolen, with a report from Elisângela Mendonça