Visitors to Detroit these days may chance upon a surprising sight: a sleek red-and-white streetcar gliding down the city's central avenue, sounding an occasional warning with a recorded toot of its electronic steam whistle. The digital readout above the windshield says "Hello Detroit."

The QLine, the city's first foray into high-order transit in decades, opens officially on May 12. As the big day approaches, drivers are testing the $4.6-million (Canadian) vehicles by running them up and down their new tracks. Bright signs warn cyclists: "Watch for rail."

A lot is riding on the project. Civic leaders are counting on it to boost the modest comeback the city has been enjoying since it emerged from a traumatic bankruptcy that made headlines around the world. The private group behind the streetcar says just the prospect of the new line has helped draw people back to the city to live and invest, lending Detroit a new buzz.

"I can remember when this place was hoppin' and when this place was desolate," says chief operating officer Paul Childs, a long-time Detroiter. "It is getting a lot closer to hoppin' now."

Chief operating officer Paul Childs, in his office at the Penske Tech Center.

M-1 Rail workers gather for a morning meeting at the Penske Tech Center.

Dan Miller, a consultant from Transdev, takes a look under a QLine car.

Can a streetcar save Detroit? The notion seems far-fetched. This, after all, is the Motor City. The car is not just king, but emperor. The wheeled revolution that began when Henry Ford walked into town from his family farm at the age of 16 to look for work in local machine shops transformed Detroit into what it is today: a city of looping expressways and broad boulevards designed exclusively for drivers. Attempts to build a modern public-transit system have failed again and again.

QLine backers insist this project is different. The 22-metre-long streetcars from Pennsylvania's Brookville Equipment Corp. have air conditioning, WiFi, security cameras, inside bike racks and low floors so that they are accessible to people with disabilities. Their lithium-ion battery packs allow them to run without wires for 60 per cent of the route. Each of the cars carries up to 125 passengers.

The cars will run mostly along the curb lane, picking up passengers from heated glass-walled stations, each sponsored by a company or institution. Developers, philanthropists and other private interests put up $130-million of the $190-million construction cost.

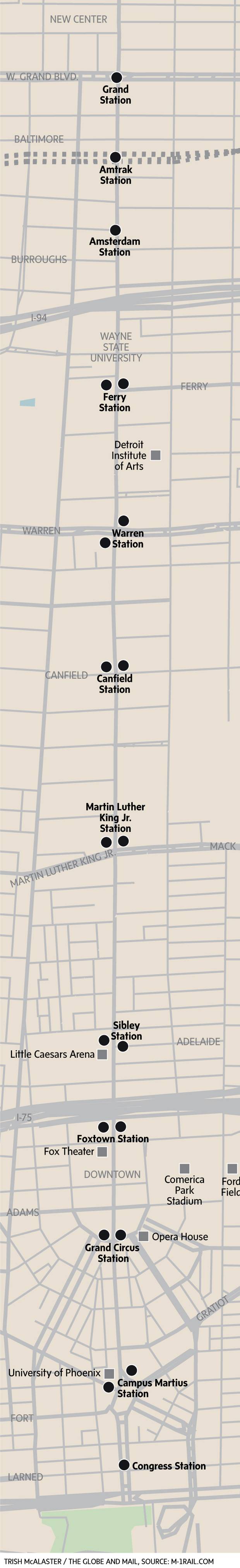

The streetcar travels on historic Woodward Avenue, the spine of Detroit's reviving downtown. Starting near the Detroit River and ending in the New Center business district to the north, it passes some of Detroit's main attractions, from the office buildings and sports stadiums of downtown to the theatres and cultural institutions of midtown. On or just off its route lie a huge medical complex; a big university, Wayne State; a leading art museum, the Detroit Institute of Arts; the restored Fox Theatre; Comerica Park, home of baseball's Tigers; and Little Caesars Arena, where hockey's Red Wings and basketball's Pistons will play after it opens later this year.

A QLine car is tested on Woodward Avenue.

The shiny streetcar also passes stark evidence of Detroit's decades-long decline: vast empty lots and boarded-up stores. Vacant, tumbledown houses and burned-out churches stand minutes away.

In one sense, the project is a bet on the future. Its backers are gambling that Detroit's revival is only getting started and that, one day, the debut of the QLine will be seen as a landmark in the renaissance of a great American city. In another sense, the streetcar is a return to the past. During construction, workers found the heavy rails of old streetcar lines buried beneath the asphalt. A rusted piece of a recovered rail sits in the project's head office.

A hundred years ago, Detroit had one of the biggest transit networks in the United States. At one point, its street railways boasted 1,600 cars. Travellers could ride as far as Flint, Mich., and Toledo, Ohio, on interurban lines. On top of that was the extensive passenger-rail system that linked Detroit to Chicago, New York and other cities around the country.

A portent of change came when Detroit's first horseless carriage drove down Woodward on March 6, 1896. The relentless rise of the automobile had begun. Proposals to build a Detroit subway faltered and failed. Buses began to replace streetcars. The last one trundled down Woodward in 1956. The rail system withered, too. Today, the monumental Michigan Central Station stands abandoned, a pathetic symbol of the city's collapse.

Michigan Central Station closed its doors in the 1980s. It has stood empty since then.

Old light-rail transit tracks, worn through the asphalt, on Michigan Avenue.

Detroit's only previous foray into modern transit is a joke. The downtown People Mover launched in 1987. Running a circular route on raised tracks, it resembles one of those shuttles that takes passengers from one airport terminal to another. Detroiters nicknamed it the Person Mover because it is so underused, it sometimes carries just one passenger. Indeed, on one recent weekday afternoon, precisely one man was waiting to board at the Cobo Center station.

The People Mover passes an abandoned high rise in downtown Detroit.

It is no surprise, then, that along with its boosters, the QLine has lots of doubters. A headline in the Metro Times, an alternative weekly, called it "a streetcar that leaves much to be desired."

Some say it is simply too little, too late. With just six streetcars on a five-kilometre back-and-forth shuttle, it is far too short to make any difference for most commuters, who will continue to rely on the city's inadequate bus system.

The line's builders estimate it will carry just 5,000 to 8,000 riders a day, a fraction of the more than 100,000 that take city buses. Compare that with the 65,000 a day that ride Toronto's King streetcar or the 55,000 a day that ride Vancouver's 99 B-Line bus.

Others dismiss the Qline as a pet project of wealthy developers that will do nothing for the city's average residents, most of them black and many poor. Rather than light rail, they say this is "white rail."

U.S. cities from Cincinnati to Charlotte to Kansas City have built new streetcar lines as light-rail transit comes back in fashion. Jeff Brown, a professor of urban planning at Florida State University, complains that planners often build them more to promote development than get people from A to B. "The interests that promote streetcars tend to be the same groups that have previously promoted downtown stadiums, convention centres and similar investments," he wrote in an e-mail.

In Detroit, residents in the city centre often commute not to downtown offices but to workplaces in the suburbs. Those who work in downtown offices usually commute in from the suburbs by car. Skeptics say the streetcar will be no good for either group. Only tourists and cool young loft dwellers will get any use from it. "It's just going to be the hipster express," says John K. King, who owns a mammoth used-book store downtown. "It doesn't go anywhere."

At the other end of the line, at a coffee bar in New Center, Sam Falik, 32, says the hype around it is just more "blah, blah, blah, everything is great, Detroit is coming back." He fears that the streetcar will do little more than "ferry people downtown to spend money."

But getting people downtown is the whole point. Just a few years ago, many Detroiters avoided the city centre, spooked by the ghostly abandoned buildings and rampant crime. Almost a quarter of a million people moved out of Detroit in the first decade of this century. From its peak of 1.8 million in 1950, its population has fallen to below 700,000. What was once the fourth-most populous U.S. city, now has fewer residents than Charlotte, N.C.

Now, signs of life are returning. The office-vacancy rate is the lowest in a decade, standing at 13.3 per cent in the past three months of 2016. Ten years back, one in three office spaces stood vacant.

High-end retailers such as Vancouver-based Kit and Ace have come in. New galleries, pubs, coffee bars and craft breweries are popping up in gentrifying neighbourhoods such as Corktown, west of downtown.

To brighten dim city streets, authorities have installed 65,000 new LED streetlights. To lighten the tyranny of the car, they have put in bike lanes and turned some one-way streets into two-way. A new bike-share system is set to start up this spring.

Dan Gilbert, the billionaire behind mortgage lender Quicken Loans, has been snapping up Detroit properties. His company paid $5-million for the naming rights to the streetcar, thus " QLine." He hopes to build the city's tallest building on a downtown lot that was once home to a famous department store, Hudson's.

The former site of the Hudson’s department store in downtown Detroit.

Its builders say the streetcar project should generate $3-billion in development and 10,000 housing units within 10 years. Businesses along the line hope it will bring more shoppers to Woodward, which can be pretty barren for the main drag of a major city.

"It will be something new and cool," says Jason Johnson, 35, who runs Bob's Classic Kicks. He sells high-end sneakers and T-shirts from a bright high-ceiling store that used to be a methadone clinic. He acknowledges, though, that he doesn't expect to use the streetcar himself. "Me, personally, I drive a Mustang V8, so it's kind of hard to give up."

Down the street, florist John Kewish, 57, says the streetcar should be a boon for Detroit. "We've got to have some mass transit. We're way behind other cities."

Buses arrive and depart at the Rosa Parks Transit Center in Detroit.

The colourful glow of Ford Field is seen in the distance, in downtown Detroit’s Cass Corridor.

Last fall, voters rejected a tax that would have paid for a big rollout of new transit. At one point, the streetcar line was supposed to be three times as long, but the plan fell through because of cost and political wrangling.

Boosters say that a successful QLine would prove the worth of transit spending and prepare the ground for a fresh start, beginning, perhaps, with an extension of the streetcar line to the north as once planned.

As the project website gushes, the QLine "is envisioned to be one element of a future modern, world-class regional transit system where all forms of transportation, including rail, bus, vehicle, bicycle and pedestrian, are considered and utilized to build a vibrant, walkable region that includes a thriving downtown Detroit."

Whether that alluring vision takes form in the Motor City, the return of streetcars is a minor miracle. The city's first one, pulled by horses, started rolling on Aug. 27, 1863. No less than 153 years, eight months and 15 days later, a new streetcar will enter service again. For a city that has been through as much as Detroit, that can only be good news.

THE ROUTE

Where does the Qline go? A guide

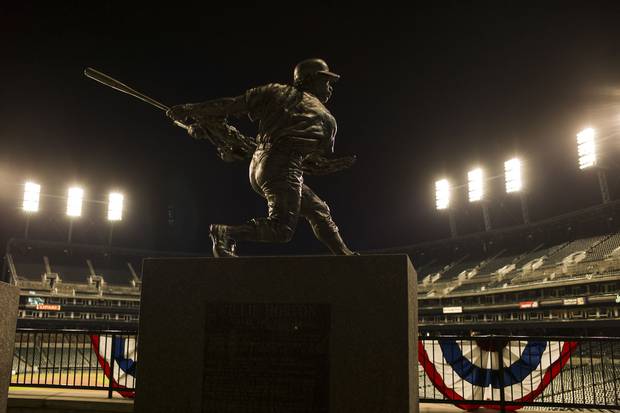

Detroit landmarks serviced by the Qline include Comerica Park, home of the Detroit Tigers …

The Fox Theatre …

The Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, featuring silk organza banners by artist Dana Hoey …

… and the campus of Wayne State University.

ARCHITECTURE

New owners aim to polish Detroit's architectural crown jewel to its former brilliance

by Marcus Gee

The sun rises over Detroit’s Fisher Building, an Art Deco landmark that sold two years ago for only $16.6-million (Canadian) – a casualty of plummeting real-estate prices in the Motor City.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY IAN WILLMS FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The Fisher Building has been called Detroit's largest art object. The art-deco masterpiece by leading 1920s architect Albert Kahn features a 28-storey tower and a barrel-vaulted ground-floor arcade decorated by murals, chandeliers and more than 40 kinds of marble.

Peter Cummings and his partners picked it up in 2015 for – hold your breath – $16.6-million (Canadian), about the same amount a seller was asking for a single luxury condo in Toronto's Yorkville district that year. Oh, and included in the price was a collection of 2,000 parking spaces in two separate garages and four surface lots, as well as the Albert Kahn Building, a grand 11-storey edifice by the same architect.

One of the effects of Detroit's long descent was a collapse in real estate prices. As businesses and residents fled for the suburbs, some residential and office properties lost almost all their market value. Many classic buildings from the Motor City's golden age were simply abandoned, leaving Detroit full of majestic ruins that tourists now examine with horrified fascination. One opulent movie palace, the Michigan Theatre, was converted into what one writer called the world's only baroque parking garage, with ranks of cars under its ornate, decayed ceilings.

Now, with Detroit stirring back to life, developers are buying up and restoring the city's remaining jewels. "The tide has turned here in such a palpable way that these hidden treasures are starting to be discovered and polished," says Mr. Cummings, an elegant 69-year-old who grew up in Montreal.

The Fisher is the brightest treasure of all. It was built by Detroit's Fisher brothers, who got rich making auto bodies for General Motors. They told Mr. Kahn to spare no expense. He made them a palace, with a gold-roofed tower clad in granite and marble. The lavish Fisher Theatre inside – still operating in more modern guise – was designed to look like a Mayan temple.

To adorn the arcade, Mr. Kahn brought in Hungarian artist Geza Maroti, who designed the mosaics, sculpture and murals. The hand-painted ceiling was ornamented with gold leaf. Even the elevator doors are works of art, decorated with a series of embossed figures representing music, commerce and other fields. The building, says Mr. Cummings, is "an extraordinary piece of architecture from an extraordinary time in American history."

People walk through the main arcade of the Fisher Building.

Like so much of old Detroit, the Fisher faded after 1967 race riots sent the city into a tailspin. Tenants moved out, maintenance declined. When it went on the auction block in 2015, Mr. Cummings and his partners saw their chance. Expecting it to go for $25-million to $40-million, they were thrilled when their online bid of $16-million came up a winner – in part because of a slip up. It seems a rival bidder mistakenly typed three extra zeroes, thrusting his bid into the billions, which the auction system rejected.

Mr. Cummings likes to see the restoration of his beloved Fisher as a symbol. He says he has "a deep emotional attachment" to the building, and to his adopted city. "I think you have to be passionate about Detroit to dig in and make a difference here."

He went to Montreal's Westmount High School, across the city from Town of Mount Royal High where Heather Reisman, a childhood friend and the founder of the Indigo bookstore chain, was a student. He studied literature at Yale and then at the University of Toronto, sitting at the feet of Robertson Davies. He got into the real estate game in Florida and married a Detroiter whose father, Max Fisher, no relation of the Fisher brothers, was an oil and property magnate.

Drawn to "the grittiness of the history and the sort of raw culture of the city," he became a leading local developer and philanthropist in his own right. One recent coup was helping to bring an upscale Whole Foods supermarket to the city's midtown district. Leaving behind his Florida real estate interests and taking an apartment in the David Whitney Building, another restored classic, he now works out of an office on the 23rd floor of the Fisher. A resident peregrine falcon swoops by the window as he speaks.

Mr. Cummings has his work cut out for him. After years of neglect, the Fisher is still only 60 per cent occupied. He says his group will put about $130-million into sprucing up the building and its related properties. They are starting with the brilliant three-storey arcade, which he proudly calls the greatest public space in the city. Workers on scaffolding are restoring the elaborate ceilings, damaged by smoke, grime and water. Among the images painted there are stylized eagles, their wings spread wide, soaring to the sky.

TRANSIT AND URBAN RENEWAL: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL