The unprecedented outbreak of a highly contagious form of plague in Madagascar's capital of Tananarive could "explode" if local and international efforts to contain the epidemic fall short, a Canadian assessment team deployed by the Red Cross says.

The epidemic has made its way into the congested metropolis of just over two million people.

While the World Health Organization (WHO) believes the risk of global spread is low, there is a moderate risk the disease could spread to neighbouring countries in east and southern Africa and a very high risk of spread locally.

Since the first case was reported on Aug. 31 in Ankazobe district, more than 1,300 cases of suspected, probable and confirmed plague have been identified, and 102 people have died in 18 of Madagascar's 22 regions. In 2014, considered a bad year for plague in Madagascar, only 40 people died. The United Nations says the rapid increase in cases is cause for concern and that "the situation will continue to deteriorate."

"This year, we are seeing urban spread of the pneumonic type" said Tonje Tingberg, the Red Cross field team leader in the country. Two-thirds of cases this year are the highly contagious pneumonic plague, which infects the lungs and is transmitted in the air, unlike the bubonic form of plague that is endemic in rural Madagascar, and which is only transmitted by fleas living on rats. Unlike most years, the plague has hit cities where person-to-person transmission is easier due to urban density and poor sanitation. Schools across the country have been closed and the government has banned public gatherings to reduce the risk of transmission.

Stephane Michaud, director of emergencies at the Canadian Red Cross, told The Globe and Mail that local health officials are operating plague-treatment centres that are currently meeting the demand. "For now, they are able to handle the clinical caseload of plague, and the main effort is at the community level to prevent further spread of the disease," he said. That effort is being led by 2,600 volunteers from the local Red Cross, with "surge support" from an international group of humanitarian aid workers, including Canadians.

Doctors and nurses from the Ministry of Health and officers of the Malagasy Red Cross staff a health-care checkpoint in Ampasapito district on Oct. 5, 2017, with the mission of informing passengers leaving Tananarive, and to potentially detect cases suspected of plague.

RIJASOLO/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

A young woman, left, gestures as she is examined by doctors at the health-care checkpoint. Two-thirds of Madagascar’s plague cases this year are the highly contagious and airborne pneumonic type.

RIJASOLO/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

The International Federation of the Red Cross is flying a specialized infectious disease field hospital to the region in case the situation worsens, and the WHO has sent 1.2 million doses of antibiotics to treat those infected and prevent illness in those exposed.

Lessons learned from the global Ebola epidemic in 2014 are being applied by international aid agencies. "We are validating the lessons we learned from Ebola," Mr. Michaud said. Those actions include five principles of epidemic containment, the most important of which is communicating with the public to demystify the illness and educate people about prevention methods. Battling stigma is a key priority.

Clinical treatment centres provide medical support to those infected while disease detectives map the disease and trace anyone who may have come into contact with an infected individual. Contacts are then provided with prophylactic antibiotics. The Red Cross is currently devising an approach to ensure the safe and dignified burial of those who die. Lastly, survivors and health care workers are offered psychological support; post traumatic stress disorder was a common consequence for those involved in the Ebola crisis.

A sixth strategy is specific to plague – vector control. "Prioritize the elimination of fleas before the [elimination of] rats, or else the fleas will hop to another host," Ms. Tingberg said. But that method of disinfection won't limit the spread of person-to-person transmission of the pneumonic plague.

It's too early to tell, says the Red Cross, if these containment strategies are working to stop the spread of the disease.

Ms. Tingberg believes two factors explain why this year's plague outbreak is worse than previous years. The highly contagious pneumonic variety of plague was introduced to the main city of Tananarive by a man who travelled to the city by taxi seeking medical help and later died. While the WHO describes plague as a "disease of poverty," the epidemic is affecting people across the socioeconomic spectrum as it spreads through the capital.

EXPLAINER

Pneumonic plague: Five things to know

Five skeletons are unearthed from England’s East Smithfield site, a ‘plague pit’ used in the 14th century as a mass grave for victims of the Black Death.

MUSEUM OF LONDON

1. What is the plague?

Plague, famously known as the "Black Death" that killed 50 million Europeans in the 14th century, is a disease caused by the bacterium yersenia pestis, and is transmitted to humans by fleas and rat bites. While Canada hasn't had a case since 1939, the United States had 16 cases last year, and four deaths, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The disease first arrived in North America on rat-infested 19th-century ships from Asia, where it can be traced back thousands of years. There is no vaccine, but it is easy to treat with antibiotics. It is still endemic in many developing countries.

2. Why is the current outbreak so worrisome?

The current outbreak is "pneumonic," meaning it affects the lungs and is easily transmitted between people through droplets in the air. That makes it highly contagious. There are approximately 400 cases of the less-transmissible "bubonic" plague each year in Madagascar, which can only be transmitted by fleas living on rats. Particularly worrisome is that this outbreak has spread to large, congested cities, increasing the risk that infected people will come in close contact with others and spread the disease. Complicating matters is the geography of Madagascar. It is a mostly rural country with poor road infrastructure, making it difficult for health teams to quickly respond to communities in need.

3. What is being done to contain the outbreak?

The Red Cross and other NGOs are on the ground assessing the situation. "We are adopting a no-regrets approach to this response," international Red Cross president Elhadj Sy said. "Our experience in responding to disease outbreaks is that quick, decisive action can save lives." The International Federation of the Red Cross is flying a specialized infectious disease field hospital to Madagascar should it need to be deployed. "Local plague treatment centres for the moment are coping, but we don't want to hold back and we are prepositioning it in case it is needed," Stéphane Michaud, director of emergencies at the Canadian Red Cross. People exposed to the disease are being tracked and provided with prophylactic antibiotics. "Vector control specialists" – rat chasers – are working to control the pest problem, and surveillance at ports of entry is being enhanced.

4. How does this outbreak differ from the West Africa Ebola epidemic of 2014?

Plague is a well-understood bacterium endemic to Madagascar. There is local expertise to recognize and treat it, and it can be cured with antibiotics. About 8 per cent of patients in this current outbreak have died. Ebola kills 80 per cent of those infected. A relatively new virus that causes bleeding, dehydration and shock, there is no cure and no vaccine. But plague is easier to transmit than Ebola – the pneumonic variant is spread by droplets in the air, while Ebola is transmitted by direct contact with feces or blood. That means more people might be infected in a plague epidemic, but fewer will die if the local health system is capable of treating them. Plague also presents with symptoms quickly – in about 24 hours – so infected individuals are often identified before they can spread the disease. Since 2014, international aid agencies such as the Red Cross have studied the Ebola outbreak and the failings of the response to the epidemic. They learned a lot – and those lessons are being put to the test right now on the streets of Tananarive and other cities in Madagascar.

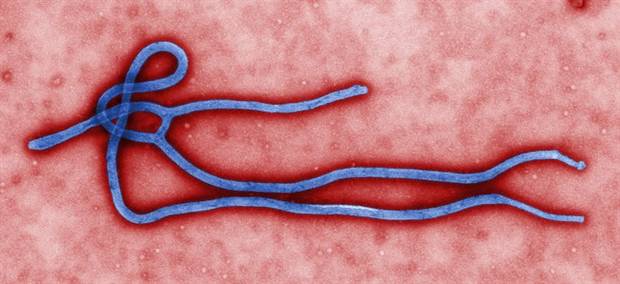

The Ebola virus, shown in an undated handout from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

U.S. CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL/ASSOCIATED PRESS

5. Could the outbreak spread?

Yes. Sputum samples from multiple suspected cases in the Seychelles, an African archipelago hundreds of kilometres from Madagascar, have been shipped to the WHO's testing facility in France. All samples tested negative, but authorities are on alert. The outbreak could be spread to other countries by plane or ship, where it could spread from person to person. Because many African cities have limited health resources and little if any extra hospital capacity, even small outbreaks can get out of -control and devastate communities. The WHO is currently in seven African countries preparing for possible spread and classifies the risk of spread outside Madagascar as "moderate."

THE GLOBE IN AFRICA: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL