Sitting on wooden benches inside a former warehouse, the Omran brothers are eating their first meal in Germany. There are open-faced sandwiches with cold cuts and cucumbers, bars of chocolate, pastries wrapped in plastic, apples and bottles of water, all served by volunteers wearing orange vests. At the door of the warehouse, there are balloons and a colourful hand-drawn sign: Welcome to Munich.

Basil Omran, 30, looks around smiling. He is thinking about how he wants to shower and then sleep for three days straight. He is amazed by the brisk and extensive help on offer, an abrupt change from Hungary – “like the difference between the sky and the ground,” he says, opening his arms to illustrate.

And while he exults that his long journey is over, he is gripped by sadness at the thought of his parents still in Deir al-Zor, Syria.

In the giddiness of arrival, it’s time to reveal a secret of their trip. Basil’s brother Osama, 24, starts unwinding the bandages around the stump of his left leg. It is amputated just beneath the knee, the result of a bombing by the Syrian army. Osama, who has travelled this entire way on crutches, grins at my discomfort. Then he points to what he is trying to show me: In between the two layers of bandages is a modest wad of euros. It’s a stratagem that has kept their cash safe until Munich.

After they finish their food, the three brothers – Basil, Osama and Zaynelabedin, the youngest at 21 – board a bus waiting outside, together with 60 other refugees. They speed through the nighttime streets of this orderly city, past tram tracks and through tunnels. The roads grow less populated and the ride feels endless. After an hour, the bus stops, then sits in the darkness with its engine running for another hour. Outside, there is an aging sign for a tennis centre: This is where they will spend their first night in their new home.

For the Omran brothers and the thousands of other refugees who crossed from Hungary into Austria and then to Germany on the weekend, these are the last steps of an epic journey and the beginning of an entirely different one. By reaching their destination, these migrants have forced Europe to confront fundamental and divisive questions: How will it treat such people, and what will it do with the many still attempting the trip?

For now, the border between Hungary and Austria remains open, as is the route to Germany, a place that many refugees talk about as a kind of promised land. On Saturday, the Omran brothers were among the more than 6,800 who arrived in the country; a further 5,000 were expected on Sunday. Now it appears they were part of a one-time exodus, rather than a policy shift: Austria’s Chancellor Werner Faymann said Sunday that his country would move “away from emergency measures and toward normality.”

The road to Vienna

For the Omran brothers, Europe’s migration-policy dilemma boiled down to one essential question: How on Earth were they going to get out of Hungary? They spent more than a week sleeping on the concrete surrounding Budapest’s Keleti station. Smugglers were offering to take people over the border with Austria for €600 a head, a price they couldn’t afford. On Friday, when hundreds of migrants set out from the station vowing to reach the border on foot, the brothers stayed put – they knew Osama couldn’t manage such a distance on crutches.

Osama was a university student when he was injured 2 1/2 years ago. As he walked down the street, a bomb dropped by the Syrian air force exploded nearby, maiming his leg and killing his friend. For his elder brother Basil, getting Osama to a place where he can be fitted for a prosthetic limb is one of the main motivations behind the journey to Europe. Otherwise, Basil says, he would be tempted to stay and fight against both Bashar al-Assad, Syria’s President, and the Islamic State, which now controls much of his hometown.

The Syrian leader “has stolen everything,” Basil says bitterly. “He has stolen oil, he has stolen money, he has stolen dreams.” Meanwhile, after a new Islamic State offensive in 2014, it became dangerous for someone like Basil, a teacher of formal Arabic, to stay. He says the IS fighters delivered a threat to all the school teachers in the city – either endorse the group and its ideology or be killed. Basil fled to Turkey a year ago. Osama and Zaynelabedin arrived there this summer.

In preparation for their journey, the brothers sold everything they could to raise funds, including Basil’s laptop, Osama’s car, even the family freezer. Finally, at the start of August, they moved toward the Turkish coast. Their parents stayed in Syria, while an older brother and a sister now live in Turkey. Basil, a slender man with a cropped beard, admits to packing one indulgence in his bag: hair gel.

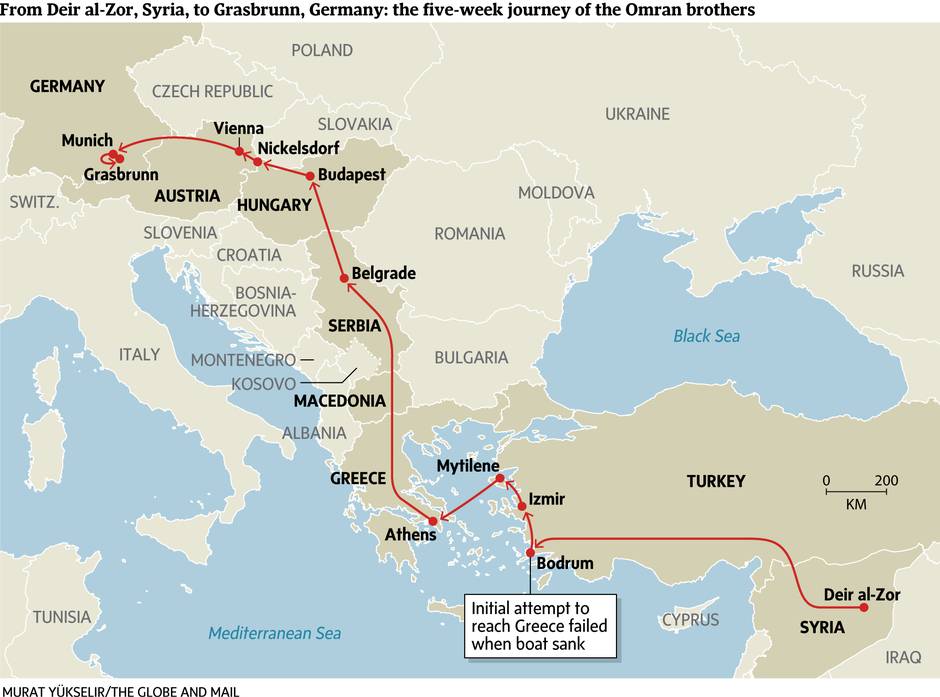

Their first attempt to reach Greece was a disaster. The boat broke down off Bodrum and sank in the middle of the night, forcing them all into the sea in their lifejackets until they were rescued by Turkish authorities an hour later. Luckily, no one drowned. They lost everything they had with them, however, including much of their money. Three days later, they tried again, and this time they reached the Greek island of Lesbos. To save their diminished resources, they ate just once a day, usually bread and apples.

After that, they took a ferry to Athens, a bus to Macedonia and a train through Serbia. At the Serbian border with Hungary, a smuggler led them through the forest at night to avoid police patrols. When Osama would tire, the crutches chafing against his arms, his brothers would remind him of what they were walking toward – Germany, a peaceful place where it would be possible to get a prosthetic.

In Hungary, they were detained twice by police, and later released. When the Hungarian authorities opened Keleti station on Thursday after barring entry to refugees, the brothers suspected a trick. They realized that none of the trains leaving that day was going directly to Germany, so they waited. About 36 hours later, their patience paid off when the government bowed to pressure and provided buses to take refugees from Keleti to the Austrian border.

Once they crossed the border into Austria, there were smiling faces, hot tea, medical care for Osama and a donated blue-and-black jacket for Basil. “Any Austrian person is an angel,” he says, laughing.

Train of hope

By midday on Saturday, Vienna’s Westbahnhof station is thronged with refugees who have crossed the border from Hungary. There are huge numbers of volunteers handing out apples, water, chocolate, flatbreads, sandwiches and donated clothes.

There are large charitable organizations in action but also individuals doing whatever they can: A young woman is standing by herself amid the crowd, offering a small tray laden with cookies and paper cups of tea; an architecture student is handing out a homemade list of key phrases translated into Arabic, German and English. Volunteer translators appear to be everywhere, with signs taped to their front and back listing the languages they speak.

A first train leaves for Munich packed with people. When the next direct train pulls up to a nearby platform, there is another mad rush down the platform. Basil, Osama and Zaynalabedin move as rapidly as they can to the front of the train, where they occupy the first seats they see.

The train is plush and clean and outfitted with luxuries no refugee takes for granted: power outlets at every seat and free wireless Internet. After the initial dash to find seats, everyone grows quiet as they wait for the train to depart. Then there is a little jolt and the train slides noiselessly out of the station.

It’s as though there is an unspoken understanding that this will not be a loud, boisterous ride. All the refugees are beyond exhausted and sleeping on every available surface. There are people sitting in the aisle and lying down on the floor and stretched out on top of the luggage racks. There are young men crammed into the junctures of the train cars, some of them smoking. There is no ticket check.

Two and a half hours after leaving Vienna, the train arrives in Salzburg, on the border with Germany. A few minutes later, the train passes a golf club, a lumber yard and a river. There are no shouts or exclamations as we cross the frontier, only the low rumble of a train going nearly 150 kilometres an hour. We pass by the station of Freilassing, the first in Germany, and I point it out to the brothers. “I’m very happy,” says Basil, his eyes shining. “Praise be to God.” Some passengers give the thumbs-up sign; others are fast asleep.

We pass by green fields, craggy mountains and dark forests. Osama makes a heart shape with his hands and puts them to the window: Germany the beloved.

Onward

It is nearly midnight when the refugees get off the bus at the tennis centre to the east of Munich which has been repurposed to serve as their accommodation. At the central train station, they arrived to a smattering of applause and cheers but also discovered a considerable number of police, who were polite yet firm in directing the refugees where to go.

They wait in the cold night air for a perfunctory health check in a white tent. Then, finally, it is time to sleep inside the old indoor tennis courts, large half-cylinders made of wood with a slightly musty smell. On each cot is a clean sheet, duvet, pillow and pillowcase wrapped in plastic.

The next morning is a slow one. Basil is up first but Osama clings to sleep. When he wakes up, he says that at first he didn’t realize where he was and thought he was still in Hungary. He can’t believe that he’s actually in Munich.

The prior evening, Osama sent word to a friend and neighbour in Deir al-Zor that the brothers had arrived safely in Germany, asking the friend to tell their parents. I share my Internet connection with Basil and he opens his phone to find a flood of congratulatory messages. There are emoticons (roses, smiley faces, clapping hands, dancers) and notes from friends, one of whom says he plans to hand out money and chocolates to everyone he sees today in celebration. Another sends a picture of Angela Merkel, with the words “I love you” in Arabic and German.

Basil is beaming, happier than I have seen him during the whole journey as a result of this brief connection with home. Their father has also sent a message, via the neighbour. It is simple but direct: Don’t come back to Syria; stay in Germany.

Monday, the brothers say, they will move to another centre and go through a more formal registration. They are hoping to settle down in Hamburg, where they have friends and where they have heard that the processing of refugee claims takes less time. There are no controls on their movement at the centre. (Indeed, on my way out, a group of 10 young men near the road ask me for directions to Belgium.)

For today at least, Basil and Osama are not in a hurry. They will go find Zaynalabedin. Osama is hungry for breakfast and Basil will finally get his shower.

Editor’s note: Since this article was originally published, two of the Omran brothers have adopted different spellings of their given names: Basil now uses Basel, and Zaynalabedin now uses Zain El Abedin. Read the latest instalment of their story here.