THE WORLD IN 2015: Elections, emerging economics and renewed conflicts. Our correspondents highlight prospects for the new year in key regions across the globe

In Africa, ethnic fault lines and iron fists bode ill

One of Africa’s most heroic and inspiring stories in 2014 was that of the Catholic priest who risked his life to save nearly 700 Muslims from near-certain death at the murderous hands of a largely Christian militia in the Central African Republic. The priest, 31-year-old Xavier-Arnauld Fagba, opened his doors to shelter the Muslims for weeks, even after his church was riddled with machine-gun bullets.

“They didn’t have anyone to help them,” he explained softly. “I did it in the name of my faith.”

Yet in many parts of Africa last year, there weren’t enough heroic leaders like Father Fagba to stem a growing tide of bloodshed by ethnic and religious-based militias and repressive armies. A vital question for 2015 is whether Africa can revive the traditional peace-building skills that helped people of different tribes and religions to live side by side for centuries.

If those peacemakers cannot be found, the bloodshed is likely to grow worse this year, from Nigeria and Kenya to South Sudan and Libya, destabilizing fragile democracies and sabotaging the economic growth that Africa desperately needs.

Africa’s religious and ethnic fault lines, deepened by economic inequities and exploited by ambitious rebels and politicians, are under growing pressure from all sides today. Islamist radicals, tribal militias, authoritarian regimes and lawless militaries have fuelled a cycle of murder, revenge, territorial grabs and terrorist attacks. Peace talks have largely failed so far, and the violence could grow far deadlier if political leaders cannot find a way to follow the selfless path of Father Fagba.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. The death of Nelson Mandela a year ago was a reminder of a more heroic age when oppressors were defeated, African unity seemed possible, and politicians willingly chose reconciliation and forgiveness. The example of peace in South Africa, after Mr. Mandela negotiated the downfall of apartheid in 1994, seemed a moral beacon for the continent.

After the collapse of the Cold War and the South African liberation, many of Africa’s civil wars soon fizzled to an inglorious end. Their foreign sponsors were largely gone or withdrawing. The Soviet Union and the apartheid regime in Pretoria weren’t financing military conflicts any more, and the United States was less interested in proxy battles.

New institutions seemed able to bring peace to Africa. The UN was creating peacekeeping forces for several African war zones. The African Union, with its noble pan-African sentiments, dispatched its own mediators across the continent to negotiate peace. The most bloodthirsty dictators, from Congo and Uganda to Ethiopia and the Central African Republic, were toppled or forced into exile. In many countries, military regimes were replaced by fledgling democracies.

It was easy to be optimistic in those days, to dream of an Africa of peace, stability, freedom and economic growth. There were signs that it was already beginning to happen, and foreign investors were pouring into the continent.

But today, a year after Mr. Mandela’s death, his message of reconciliation is increasingly ignored by the leaders of some of Africa’s most important countries, and violence is threatening to undo their economic progress. The year ahead will be a crucial test of Africa’s diplomatic and political institutions: Can they halt their internal conflicts before they turn into the kind of near-permanent wars that have scarred much of the Middle East and Central Asia?

One of the key tests will be Kenya, where violence has escalated dramatically in recent years. Kenya is one of the counties that are indispensable to Africa’s economic future. Fast– growing, technologically savvy, bolstered by a major tourism industry, seaports and energy resources, it has the power to lift other countries into a higher economic orbit.

Yet Kenya’s future has been jeopardized by Islamist terrorism and the suffocating effect of a security crackdown. Hundreds of Kenyans have been killed in massacres by domestic and foreign terrorist groups, primarily al-Shabab, the Islamist radical militia in neighbouring Somalia.

The Kenyan government has worsened the crisis with a series of iron-fisted overreactions: invading southern Somalia with thousands of troops; harassing and detaining thousands of Somali refugees without evidence of wrongdoing; and ordering deadly raids into Muslim communities, where its police squads have allegedly committed extrajudicial killings of Muslim preachers.

The government has shown little interest in a softer approach to defuse the smouldering grievances that feed the Islamist rebellions in Kenya and Somalia. If its crackdown intensifies in 2015, it will further destabilize the country, guaranteeing a cycle of reprisal attacks and allowing the extremists to build local support.

Tensions are rising sharply between Kenya’s Muslims, who represent roughly 11 per cent of the population, and the Christian majority. Kenya’s democracy, already under strain from the wave of post-election killings in 2008, will suffer further damage if violence continues to be met with violence.

Nigeria is an equally important nation, the biggest in Africa by population and economic size. If it takes off, it could stimulate growth and investment across the whole of West Africa. Yet it, too, is gripped by an unending cycle of violence between the Boko Haram rebel group and the Nigerian army forces that often respond ruthlessly with murder and abduction tactics of their own. Thousands have been killed by the two sides in the war so far, and there’s no end in sight.

The Boko Haram rebellion is far more than purely a religious conflict, but its members are primarily Muslim and it often launches brutal attacks on Christian villages. While the Nigerian government does little to negotiate with the rebels, the religious fault lines are growing dangerously unstable. National elections in February will pit a southern Christian president against a northern Muslim challenger, with many Muslims resentful at the continuing dominance of a Christian ruler, instead of the traditional rotation between the two religions and two regions.

In oil-rich South Sudan, the Dinka and Nuer ethnic groups had co-existed for centuries until fierce fighting erupted a year ago, fuelled largely by politicians jostling for national power. Since then, the war has killed anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 people, and ceasefires have repeatedly collapsed. With no apparent political willingness to negotiate a peace agreement, the fighting is widely expected to continue, leaving half the population in desperate need of humanitarian aid, while the risk of man-made famine looms.

Across the border in Sudan, the government continues to bomb rebel-held areas in the regions of Darfur, Blue Nile and South Kordofan, while human-rights groups have reported shocking abuses by government soldiers, including mass rapes. And in the Central African Republic, despite a UN peacekeeping force, hundreds of people are still being killed in sectarian clashes across much of the country.

Weak governments and abusive security forces are a key reason for the violence that seems certain to continue in 2015. But there are also growing links among the radical Islamist militias, from Somalia to Nigeria and the Sahara, providing each other with military training and ideological inspiration.

African leaders gathered in Senegal last month to warn of a growing threat from Libya, where Islamist militias are thriving in the political chaos after the overthrow of Moammar Gadhafi. The militias cross borders to the south, threatening the stability of Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and Chad. “As long as we haven’t resolved the problem in southern Libya,” Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita said at the summit, “there will be no peace in the region.”

Will a Kenyan scion choose security over freedom?

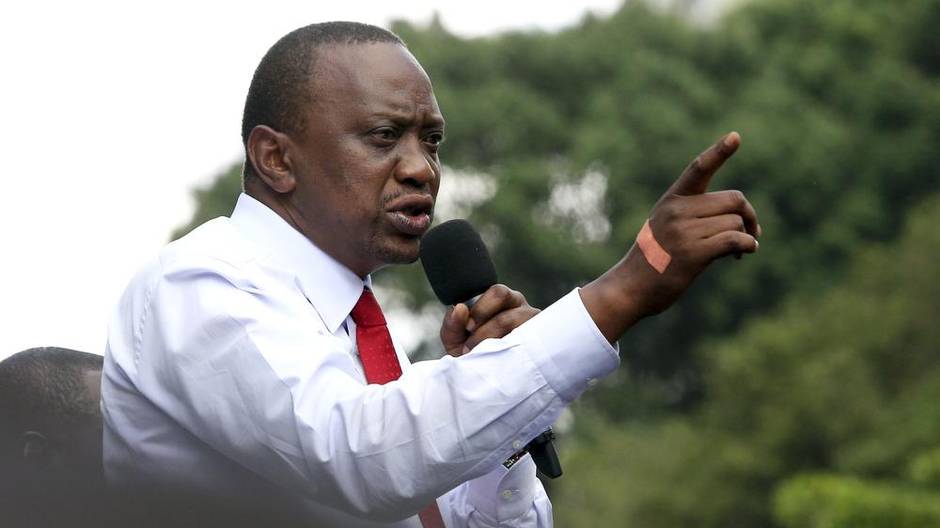

President Uhuru Kenyatta has always been the fortunate son of Kenyan politics. The scion of Kenya’s founding father, Jomo Kenyatta, he seemed to live a charmed life, narrowly escaping from legal and political battles that could have derailed his ambitions, or even put him behind bars. At 53, Mr. Kenyatta has built an estimated fortune of $500-million (U.S.) in banking, tourism, media, construction and vast land holdings, making him the 26th-richest man in Africa, according to Forbes magazine.

He has sailed through a career that made him the youngest president in Kenya’s history, but Mr. Kenyatta now faces a year of daunting challenges to his governing skills. As violence and terrorism escalate, the future of his country’s democracy will depend on whether he can choose the right balance between security crackdowns and fragile freedoms.

Kenya has been a star of African economic growth in recent years, but that progress is threatened by Islamist rebels in several regions of the country. Domestic and foreign terrorists have killed hundreds of people over the past two years and the President’s response could determine whether Kenya remains a thriving democracy or turns into a more authoritarian and militarized state.

So far, Mr. Kenyatta has opted for tough counterattacks. Last month, he pushed for a harsh new security law and got it passed by a majority of MPs, despite chaotic scenes of fistfights in parliament. The new law would allow journalists to be jailed for up to three years if they “undermine” terrorism investigations or publish photos of terrorism victims without permission. It would also allow police to obtain court orders to jail terrorism suspects for nearly a year without charges.

In a separate move, Mr. Kenyatta’s government shut down hundreds of non-governmental organizations, including some over allegations of raising funds for terrorists. Kenya’s police, meanwhile, are facing accusations of killing hundreds of Muslim suspects without trial. The police have also rounded up and detained thousands of Somali refugees on flimsy grounds.

Mr. Kenyatta has been in trouble before, but always survived. He came close to losing the 2013 election before barely reaching the necessary 50-per-cent margin. He was indicted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity, including murder and rape, in connection with the postelection violence that killed more than 1,000 Kenyans in early 2008, but the charges were dropped after the prosecution’s case fell apart – allegedly because of the bribery and intimidation of prosecution witnesses.