The political scientist who correctly predicted the results of every American presidential election in the past three decades is out with a book setting forth the case for impeaching President Donald J. Trump. Meanwhile, this week, Lawrence Tribe, the Harvard Law School professor who taught former president Barack Obama and Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan, has called for impeaching Mr. Trump because his "conduct strongly suggests that he poses a danger to our system of government." And a conservative House Republican and a House Democrat breached an important symbolic barrier Wednesday when they separately said the President's conduct might merit impeachment.

Though Mr. Trump only recently completed his first hundred days in the White House, he may already be only a few major missteps from facing more serious calls for his removal from office. This month alone he has abruptly dismissed FBI Director James Comey, who had been examining possible collusion between Trump advisers and Russian officials during last year's election; faced an assertion by Mr. Comey the President had asked him in February to shut down the investigation of former national security adviser Michael T. Flynn, who had earlier resigned amid a scandal over his contacts with the Russian ambassador to the United States; and struggled to contain a controversy over sharing classified information, with a Russian diplomat, about a planned Islamic State operation.

Those controversies culminated this week in the appointment of former FBI director Robert Mueller as special counsel to lead an investigation into "any links and/or co-ordination between the Russian government and individuals associated with the campaign of President Donald Trump," and the empowering of Mr. Mueller to press criminal charges.

Despite talk of impeachment in the air – Democratic Rep. Al Green of Texas is the latest voice, coming, in his case, in the well of the House of Representatives – the truth is that impeachment is a radical step which, by intent and tradition, is reserved for radical departures from respectable political comportment; imposes extreme stresses on the political system; and exacts a high price not only on the president but also on the men and women who undertake the procedure.

"Political figures approach this issue very carefully," says Ken Gormley, author of The Death of American Virtue, considered the most authoritative account of the events that led to the impeachment of Bill Clinton in 1998. "There are many recourses outside impeachment for people who are upset with a president," he notes. "Talking about impeachment, getting it to happen in the House, and then having a successful Senate process are separate steps, each very difficult. And they can consume a country and waste a lot of time."

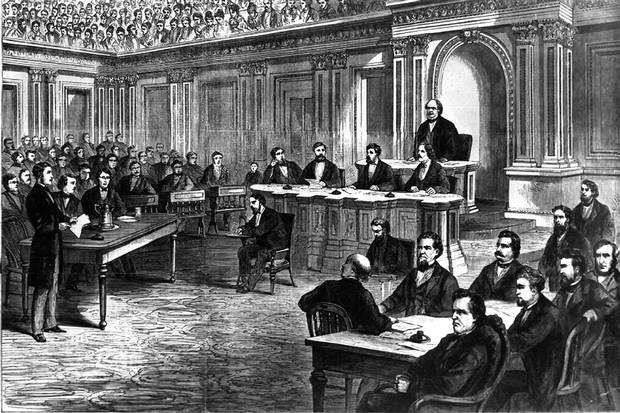

An artist’s rendering shows the public from above as the U.S. Senate opens the High Court of Impeachment during the trial of president Andrew Johnson on March 13, 1868. Johnson, the first U.S. president to be impeached in the House, kept his job by a single vote in the Senate.

U.S. SENATE HISTORICAL OFFICE/KRT

Presidential impeachment used to be one of those political instruments widely recognized but seldom employed. Only three times have American presidents been put through this ordeal. Only twice have chief executives actually been impeached. And never has a president been removed from office through this process, which requires the equivalent of an indictment by a majority vote of the House and a conviction by two-thirds of the Senate in a trial that would be presided over by another of Prof. Tribe's former students, Supreme Court Justice John Roberts.

Indeed, a full 130 years passed between the 1868 impeachment of Andrew Johnson, who survived removal by a single vote in the Senate, and the impeachment of Mr. Clinton, who never was in serious danger of conviction in the Democratic-controlled Senate of the time. During those 13 decades – a period extending from Thomas Edison's application for his first patent to Google's application for incorporation – presidents from Ulysses S. Grant to Warren G. Harding faced searing questions about their roles in major scandals, and yet no serious steps were taken toward impeaching the 18th and 29th U.S. presidents.

The late historian David E. Kyvig, one of the few academic experts on the issue of impeachment, wrote that the dormancy of impeachment could not endure. "It was often mistakenly written off as comatose, if not completely dead," he wrote in his 2008 book, The Age of Impeachment, adding that "it was merely slumbering and awaiting the call that would cause it to arise and demonstrate its vitality."

The resistance of American lawmakers to undertake formal impeachment hearings in 2017 may be eroded by the fact that Congress has already resorted to this procedure twice in the past 44 years: the Clinton impeachment growing out of his relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky; and the Richard Nixon episode that grew out of Watergate but stopped after Mr. Nixon resigned his office rather than face certain impeachment, conviction and removal from the White House.

And yet the relative frequency with which impeachment has been employed may make the process seem less forbidding to contemporary political figures.

"This is a formidable process, but it is taken more lightly now than before," says Michael Les Benedict, Ohio State University historian and author of The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson, which, since its publication in 1973 – the year before Mr. Nixon's resignation – has been regarded as the standard account of that first such levelling of charges against an American president. "Impeachment may even have become part of the ordinary lexicon of politics," says Mr. Benedict. "But the process was never thought about easily, and the word was never bandied about until recently, when it has become easier to contemplate by people who really dislike a president."

Even so, the mere mentioning of impeachment – still the congressional process that, as a rule, dare not speak its name – by two lawmakers, Representatives Justin Amash, a Michigan Republican, and Ted Deutschland, a Democrat of Florida, in a single day this week was taken as an important political moment, far more significant than the earlier casual invocations of impeachment by two Democrats, Representative Maxine Waters of California and Senator Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut. Just as knowledgeable baseball fans know not to mention that a no-hitter is in progress lest the feat be disrupted, political figures know not to mention impeachment lest the furies be unleashed.

In 1974, as in 1998 and 2017, the effort to define an impeachable crime has been at the centre of the political debate.

Impeachment has its roots in British law, dating to the 14th century, and so was familiar to the men who met in 1787 to recast the country's government by replacing the failing Articles of Confederation with the Constitution that still provides the contours of the American government. Moreover, several state constitutions in effect at the end of the 18th century provided for impeachment as a remedy for "maladministration" or "corruption" – the concept was well established in the New World when the Constitutional deliberations began.

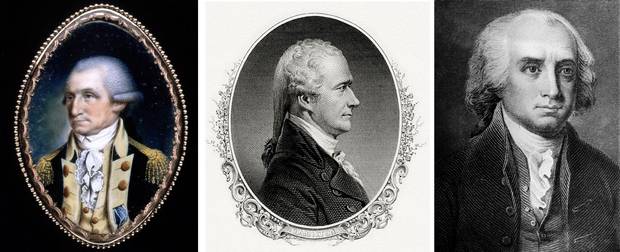

So it was natural that when these men – the group included George Washington and James Madison, who would become presidents, and Alexander Hamilton, a cerebral political theorist who later became the first secretary of the treasury – began to craft a new Constitution, they included impeachment in their early drafts.

The so-called Framers of the U.S. Constitution included George Washington, the nation’s first president; Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the treasury; and James Madison, the fourth president.

ASSOCIATED PRESS; U.S. BUREAU OF ENGRAVING AND PRINTING

Indeed, these Framers, as they became known, debated impeachment even before they decided that the new executive branch of the United States government would be headed by a single president rather than by a council of executors. A report published by the House Judiciary Committee after the effort to impeach Mr. Nixon in 1974 noted that, early in their work, the Framers unanimously endorsed a provision permitting the removal of the executive for "mal-practice or neglect of duty."

Those terms are broad, as is the eventual Constitutional language of "Treason, Bribery, or other High Crimes and Misdemeanors," and so difficult to pin down that Rep. Gerald Ford of Michigan said during the debate over whether to impeach Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, largely for political and personal reasons growing out of his four marriages, that "an impeachable offence is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history." Mr. Ford, then the minority leader of the House, had no reason in 1970, two years before the Watergate break-in, to foresee that his remarks would echo through the chambers of the Judiciary Committee that initiated an impeachment proceeding against President Nixon – an action that would catapult Mr. Ford himself into the White House.

But the remarks by Mr. Ford – who, in one of the ironies of American politics, represented the very same Grand Rapids, Mich., district now served by Mr. Amash, the GOP lawmaker who raised the spectre of a Trump impeachment – are a reminder that impeachment is as much a political process as it is a legal undertaking. It is possible that the impeachment of Mr. Nixon, the first president in 120 years to face a Congress where both chambers were controlled by the opposition party, might well not have advanced had Republicans held power in the House.

That is a central element in the political calculus affecting Mr. Trump. Although he has few historical or personal ties to the Republican Party, he was the GOP's presidential nominee in 2016, and the Republicans hold a large (241-194) advantage in the House. The margin is smaller in the Senate (52-48 – if one counts the two Independents as Democrats; they most often vote that way). But the two-thirds requirement for Senate conviction, and thus for the removal of the President, puts the target at 67 votes – a high bar that, today at least, seems out of reach.

The party profiles, and thus the chances for impeaching Mr. Trump and removing him from office, would shift dramatically if the Democrats were to take power in the House following next year's midterm congressional elections. That would require a Democratic pickup of 24 seats, a formidable swing in voter behaviours given the unusual ideological purity of some current congressional districts. But it is not out of the question; Barack Obama's Democrats lost 63 seats in the 2010 midterm congressional elections, when his approval ratings were in the general range of Mr. Trump's today.

More than four decades ago, the House Judiciary Committee, which eventually would approve articles of impeachment against Mr. Nixon, warned against broad application of congressional impeachment authority even as it asserted the right of lawmakers to proceed with actions that could lead to the removal of the president. "The elective character and political role of a President make it difficult to define faithful exercise of his powers in the abstract," the committee's report said. "A President must make policy and exercise discretion. This discretion necessarily is broad, especially in emergency situations, but the constitutional duties of a President impose limitations on its exercise."

DALIN BRINKMAN/GETTY IMAGES

The context of the debate over impeachment in the Constitutional Convention is vital to understanding the origins of this element of the American government.

The delegates met between May and September of 1787 in the very building in Philadelphia where, only 11 years earlier, the Second Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence. Both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were written as antidotes to the rule of King George III, the goal being to limit the power of any future single ruler. "The Revolution had been fought against the tyranny of a king and his council," the Judiciary Committee report emphasized, "and the framers sought to build in safeguards against executive abuse and usurpation of power." The Framers were concerned, however, that, just as executive power could be abused, impeachment, too, could be abused.

Some delegates believed that periodic elections themselves were sufficient guards against tyranny; they had not yet fixed the length of the executive term at four years, and the two-term limit for presidents wasn't ratified until 1951, after Franklin Roosevelt's four election victories from 1932 to 1944. But in the only formal test of impeachment in the final version of the Constitution, the provision passed with only two states dissenting.

In The Federalist Papers, the effort by leading American statesmen of the day to explain the Constitution, Alexander Hamilton wrote that impeachment was adopted, for the new form of government, to be a bulwark against what he called the "misconduct of public men, or in other words from the abuse or violation of some public trust."

The phrase "violation of some public trust" is at the heart of the argument being mustered by Mr. Trump's opponents as they wish for impeachment proceedings to begin. Their hope was stoked midweek when Mr. Mueller was appointed special counsel.

"We're in a situation where impeachment is mentioned quite a bit by people who think the President has gone beyond merely proposing and enacting policy that is deeply flawed," said Mr. Benedict, the authority on the impeachment of Andrew Johnson. "I'm an academic, not a politician, but I still think impeachment is the nuclear bomb of American constitutional politics."

CHIP SOMODEVILLA/GETTY IMAGES

David Shribman is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and a former campaign reporter for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal.

WHAT'S NEXT FOR TRUMP: MORE FROM THE GLOBE