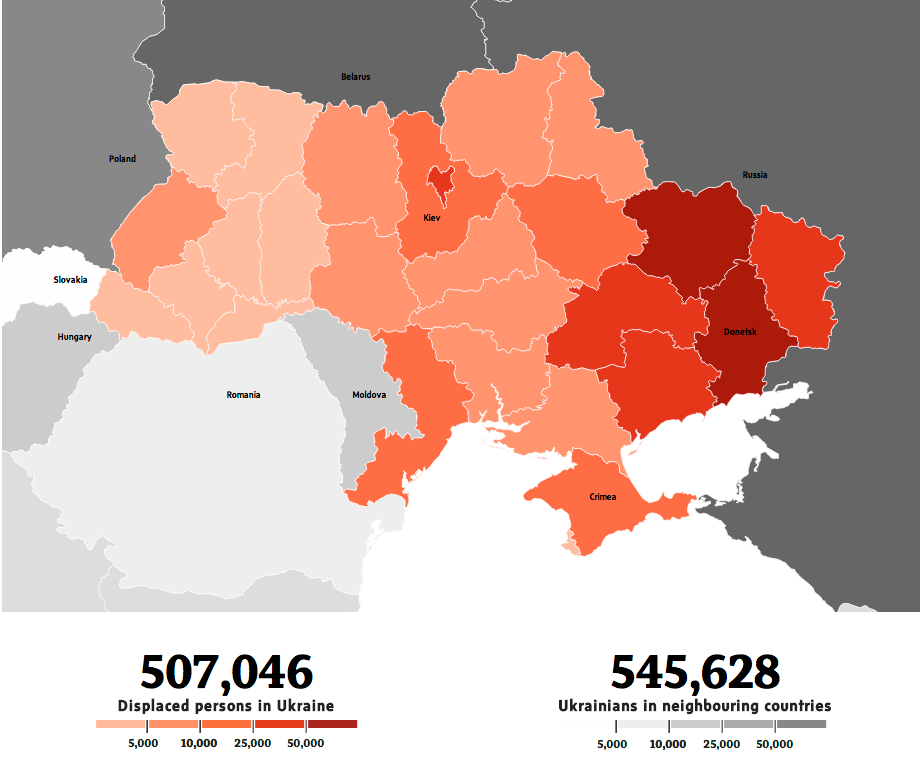

It began as a simple trade dispute and escalated into war. A year later, one million Ukrainians have been forced from their homes.

Donetsk

Total Displaced

From East

From Crimea

Displaced Ukrainians in Ukraine

Ukrainians in neighbouring countries

Elvira Sergeyevna and her family slept only a few hours. Then the war that had driven them from their home caught up with them again. The thud of incoming artillery fire jolted the 28-year-old awake.

She scrambled to collect her elderly mother and infant daughter, and to get out of the tent they had been sharing that July morning with other refugees from the battle-scarred Donetsk and Lugansk regions of eastern Ukraine. In the chaos that followed, they were told by Russian authorities that the Ukrainian army had fired the shells, and that it was no longer safe to stay in the border camp they had arrived at the night before, after a frightening 10-hour drive across a war zone.

Ms. Sergeyevna and her family next took a two-day bus trip north to St. Petersburg, but Russia’s second-largest city wouldn’t prove any more hospitable. After several weeks of both women struggling to find work in the hardscrabble outskirts (the city itself was closed to refugees by government edict), Ms. Sergeyevna proposed another move, this time to Khabarovsk, more than 8,800 kilometres away in Russia’s Far East. There were promises of free accommodations, jobs and startup cash for Ukrainian refugees – a lure to draw them to the same remote outpost that tens of thousands of their countrymen had been forcibly deported to during the Stalin era.

Eight decades later, Ukraine is once more seized by a tumult largely made in Moscow, as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin has sought to break the country into pieces in response to a pro-Western revolution in Kiev. Once again, significant parts of the population are being scattered to distant lands.

Ms. Sergeyevna’s terrifying and improbable journey to Khabarovsk is part of a new exodus of roughly a million Ukrainians who have been forced from their homes over the past 12 months, as war and exile returned to Europe for the first time since the last of the Balkan wars ended 15 years ago. What started last November as an argument over a trade deal developed into a violent uprising, then into a war and an international crisis that has seen relations between Russia and the West plunge to post-Cold War lows.

Many of those who fled eastern Ukraine, and nearly all those who remain behind, believe that the country and the sense of nationhood that existed a year ago have been destroyed – and can never be restored.

Until her escape to Khabarovsk, on Russia’s border with China, Ms. Sergeyevna lived in the Kirovsky neighbourhood in the southern part of the city of Donetsk (the region and its largest city have the same name). Only a brave few remain there now. Despite a ceasefire deal signed in September, fighting continues to rage on the edges of the city, and the boom of artillery and rocket fire remains the soundtrack of everyday life.

There appears to still be someone living inside the family’s modest concrete bungalow on Glazunova Street – there’s a car in the driveway; smoke is coming from the chimney – but no one answers the door. Ms. Sergeyevna says she believed, but wasn’t sure, that her husband stayed behind to join the militia of the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic, a Russian-backed entity at war with the Ukrainian state.

Marta Igoryevna, a former neighbour who remained in Donetsk, points out the buildings on Glazunova Street that have been hit by mortar fire. Most local businesses have closed, she says, so even those who still have some money have nowhere nearby to spend it. “We sit in the house all day on the sofa and count the missiles as they fly over. I heard 30 in one day,” says the 23-year-old mother of three. She has no work, and her parents haven’t received a pension in four months. “We aren’t living; we’re surviving.”

A collapse in stages

Last fall, Ms. Sergeyevna was home in Donetsk, watching the news from the capital, Kiev, as tensions rose over a proposed trade agreement between the European Union and Ukraine. Much of the country desperately wanted then-president Viktor Yanukovych to sign the deal, hoping it would be a step toward eventually joining the EU. But the large majority in Donetsk, and other parts of eastern and southern Ukraine, saw the pact as a dangerous change in direction, one that threatened their regions’ crucial economic ties with neighbouring Russia.

Like many of the almost 450,000 who have fled into Russia since the war began, Ms. Sergeyevna blames her plight on a bloody February revolution that ousted Mr. Yanukovych, and the subsequent rise of what she calls a “fascist” government in Kiev. To her, last year’s uprising was not about building a Ukraine with European values; it was, rather, a takeover by Ukrainian nationalists who bore violent hatred toward the country’s Russian-speaking population.

Sergei Sytyi, a 39-year-old home builder, saw it very differently. Though he grew up just a few kilometres from Ms. Sergeyevna, he was thrilled when pro-Western crowds took over Kiev’s Independence Square (better known as the Maidan), demanding the president sign the trade deal.

The demonstrations against Mr. Yanukovych began on a rainy Thursday evening, Nov. 21, 2013. Earlier that day, he had shocked the country – and much of the world – by walking away from the painstakingly negotiated EU pact, under obvious and heavy pressure from Moscow.

The first protesters converged on the Maidan that night, the beginning of what would become a rolling protest. It began as a tent city, with thousands of citizens sleeping each night on the cold pavement; it then became a crude fort, as tire-and-razor-wire barricades were built following an aborted crackdown by Mr. Yanukovych’s hated Berkut riot police.

The explosion that would set Ukraine on fire came three months later, on Feb. 18, when Mr. Yanukovych ordered the Berkut to end the demonstrations by force. Three days of violence followed – more than 100 people were killed, nearly all of them protesters who had been shot – before the president fled on Feb. 21. Ukrainians appeared to have definitively turned away from Moscow to embrace the West.

In response, Russia annexed the southern peninsula of Crimea and its two million inhabitants. The regions of Donetsk and neighbouring Lugansk declared themselves independent in April (after Mr. Putin collectively referred to them as “Novorossiya” or “New Russia”). The ensuing war against the Ukrainian army has left both sides bleeding and well short of their strategic objectives. More than 4,000 Ukrainians have died in the tumult that has followed, and no clear victors have emerged.

No safe haven

Mr. Sytyi knew he was taking a risk by going to Donetsk’s Lenin Square two weeks after Mr. Yanukovych’s ouster, to show his support for the Maidan revolution. But like the protesters in Kiev, he had grown tired of the corruption that became synonymous with Mr. Yanukovych’s reign, and with Russia’s growing influence over the country. The March rally in Donetsk was as close as the pro-European revolution came to sweeping through the eastern city. Some 5,000 protesters took part in a pro-unity demonstration, waving the blue-and-yellow Ukrainian flag. It briefly looked and felt as if what had started in Kiev couldn’t be stopped.

But there were other forces already at work in Donetsk. Earlier that day, pro-Russian demonstrators had stormed the local government headquarters, a grim Soviet-era office building that would eventually become the hub of their counter-revolution. As night fell, a crowd of about a thousand protesters waving Russian flags marched on Lenin Square, provoking a brawl that left a 22-year-old pro-Ukrainian protester dead.

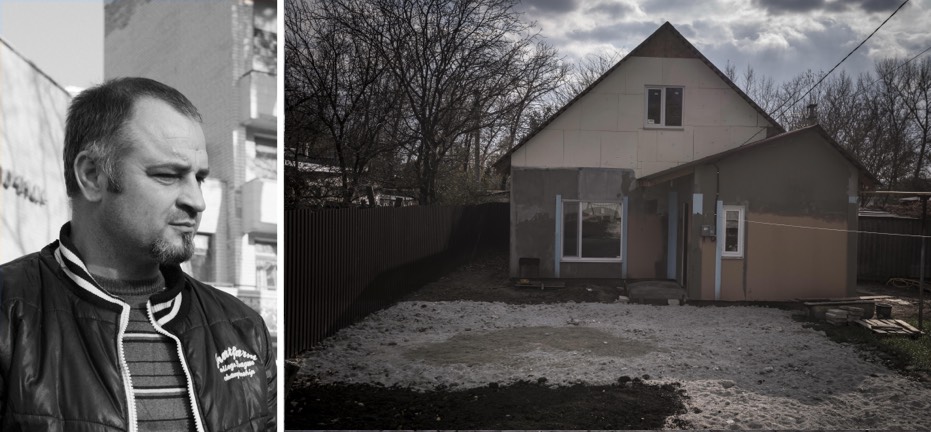

Sergei Sytyi

Age: 39

Why he left: Sergei and his family fled to Kiev after he joined a pro-Ukrainian protest in downtown Donetsk. Other participants were targeted in apparent assassination bids.

What life’s like now: The family of six live in two rooms of the disused sanatorium outside the Ukrainian capital, but say they still feel threatened there, this time by Ukrainian nationalist militias who harass Donetsk refugees. Even though Mr. Sytyi is pro-Ukrainian, “they call us separatists and Russians.”

Current location: Istochnik sanatorium, outside Kiev. The construction worker is now planning to move further west, perhaps to Germany or Spain.

Current location: Istochnik sanatorium, outside Kiev. The construction worker is now planning to move further west, perhaps to Germany or Spain.

“I stood up for my country when I was in Donetsk because I was a patriot. I'm not a patriot anymore.” – Sergei Sytyi

As the separatists’ hold over the city grew, those who took part in the pro-Maidan protests started to feel like targets. A neighbour of Mr. Sytyi who had joined the demonstration narrowly escaped when gunmen came to his house in an apparent assassination bid. Many of those walking around with guns had accents that to Mr. Sytyi’s ears sounded like those of Russian nationals. (Moscow denies accusations that it orchestrates, funds and arms the Donetsk and Lugansk separatists.)

“I asked my wife, ‘Are we ready to die?’ ” the burly military veteran recalls. Mr. Sytyi and his wife, Lilit – eight months pregnant at the time – fled northwest with their three children to Kiev, deciding they’d rather live in a Europe-facing Ukraine than a Moscow-backed eastern mini-state.

Just outside Kiev, the Sytyi family now occupies two small but comfortable rooms in a disused sanatorium. The rooms are crammed with musical instruments the children are learning to play, and Mr. Sytyi says he has been able to find occasional construction work in the city. But they haven’t escaped the war. Mr. Sytyi says they and the other refugees are frequently harassed by gunmen from the Aidar Battalion – far-right Ukrainian nationalists accused by Amnesty International of abductions, extortion and “possible executions” – who come to the sanatorium to insult and threaten the refugees with expulsion.

As discrimination toward Donetsk and Lugansk residents rises in other parts of Ukraine, Mr. Sytyi says – with regret – that he and his family feel no more at home in the Ukrainian capital than they did in so-called Novorossiya. “We have no homeland,” Ms. Sytyi says glumly as she rocks their three-month-old daughter, Sophia, who was born days after the family moved. Mr. Sytyi has given up on the idea of Ukraine ever becoming the kind of European country in which he wants his children to grow up. “I stood up for my country when I was in Donetsk because I was a patriot. I’m not a patriot any more.”

Scattered in the aftermath

Ms. Sergeyevna’s Kirovsky neighbourhood survived relatively unscathed through the first three months of warfare that followed the April 7 declaration of independence by the Donetsk People’s Republic. But on July 8 a shell struck a coal mine just south of her house, causing a blast so powerful that her concrete bungalow shook. The next day, she took one of the semi-regular buses that the separatists organized for women and children who wanted to escape the war zone, often while their husbands and fathers remained behind to fight the Ukrainian army. Three buses left from a parking lot behind the city’s circus, escorted out of the city by two cars of gunmen who took them to the Russian border.

Human-rights activists say Russia welcomes many of the eastern Ukrainian refugees – and exaggerates their number – to aid its propaganda war against the government in Kiev: The large-scale outflow of refugees supports Moscow’s contention that Russian-speakers in Ukraine feel persecuted since February’s revolution. At the same time, the migration helps Russia repopulate remote and economically troubled regions of the country with Russian-speakers of the Orthodox faith.

Elvira Sergeyevna

Age: 28

Why she left: An artillery shell struck the Petrovskaya mine, near Glazunova Street, shaking her house.

What life’s like now: She and her 2-year-old daughter Evelina share an apartment with another refugee family. She’s bitter that start-up cash promised to refugees by the Russian government hasn’t materialised. “They treat us like homeless people.”

Current location: Khabarovsk, Russian Far East

Current location: Khabarovsk, Russian Far East

“I never realized I was a patriot. Now I realize how much I loved my homeland and my city, and how sad I am at it being destroyed.” – Elvira Sergeevna

Ms. Sergeyevna feels deceived now that she’s in Khabarovsk. The communal apartment that she and her daughter share with another family is rent-free, but she says the accommodations are unclean and infested with cockroaches. (The apartment block was under unspecified quarantine when The Globe and Mail tried to visit.)

Ms. Sergeyevna is taking government courses that will qualify her for a service job on Russian railways, but the promised startup cash for a business never materialized. She doesn’t have enough money to buy fresh food for her daughter, who, she worries, is suffering from malnutrition. She says she feels monitored in Khabarovsk, and asked that her last name not be used. (“Sergeyevna” is her patronym; it means “daughter of Sergey.”)

The only time her round face smiles is when she’s asked what Donetsk was like before the war.

She fondly remembers pushing her daughter’s stroller through Scherbakov Park, which sprawls along the south bank of the city’s water reservoir. She also loved to window-shop in the luxury stores – she was too poor to go inside them – that line central Lenin Square, a plaza dominated by a giant monument to the man who founded the Soviet Union. Dozens of Lenin statues have been toppled in Ukraine over the past 12 months, but Ms. Sergeyevna and most Donetsk residents are proud that he still stands in their city.

Then the smile disappears. “Everything’s been bombed now, even the park.”

Like the Sytyis, Ms. Sergeyevna expects she’ll never return to Donetsk. All of them fear that both their city and country are doomed to a prolonged period of chaos and war. Mr. Sytyi plans to move his family farther west, into the EU itself, and to find work there. The Donetsk they once knew has been reduced to a clutch of fond memories, and a remembered sense of neighbourhood and nation that can likely never be recovered.

New government, old divisions

Today there’s a new, pro-Western government in Kiev: Petro Poroshenko and Arseniy Yatsenyuk, two key leaders of the Maidan protests, are president and prime minister, and the EU trade agreement that Mr. Yanukovych rejected was signed by Mr. Poroshenko in June.

Mustafa Nayem, a prominent journalist, is often credited with instigating the revolution against Mr. Yanukovych. (“Come on guys, let’s be serious,” he wrote to his 30,000-plus followers on Facebook, after Mr. Yanukovych walked away from the trade deal on Nov. 21 last year. “If you really want to do something, don’t just ‘like’ this post. Write that you are ready, and we can try to start something.”) Now a member of parliament, Mr. Nayem says that the revolution’s main victory is not the fresh faces in government – or even the country’s pro-Western orientation – but the fact Ukraine’s new leaders know they must respect public opinion or risk another round of protests.

“We turned away from a crossroads that was passed by Belarus and Russia. In those two countries, the younger generation are infected by Soviet-style politics. They are scared of their government, of the police, of prosecutors, of politicians,” Mr. Nayem said, in an interview with The Globe and Mail in a dimly lit hotel lobby on the edge of the square where the uprising had begun. “We did the opposite. We infected the government and the politicians with a fear of society. That’s the big difference from Belarus and Russia: Our politicians are afraid of the people, of protests, of Maidans.”

But, he says, more should have been done to reach out to Donetsk and Lugansk.

Even before the revolution and the war, Donetsk had a bad reputation in Ukraine. Like neighbouring Lugansk, the region was seen by other Ukrainians as grim and grey, a place of coal mines and Soviet-era factories that were run by corrupt oligarchs.

Donetsk, Lugansk and Crimea resisted the nation-building project under way in the rest of the country, with most residents stubbornly referring to themselves as Russians more than two decades after the USSR fell apart.

Donetsk perplexed the rest of the country even further by repeatedly supporting its native son, Mr. Yanukovych, despite his background as a petty criminal and his involvement in the massive election fraud that provoked Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution. The fallen president was born on the outskirts of Donetsk, and when he was elected president in 2010, it was with 90-per-cent support from Donetsk in the decisive second round of voting. “He was a bandit, but he was our bandit,” is how Ms. Sergeyevna explains her city’s affection for Mr. Yanukovych, who posted similar support levels in Lugansk and Crimea as well.

Donetsk made obvious gains while Mr. Yanukovych was in office, drawing four-star hotels and big-brand clothing stores to its modernized city centre. But the Kirovsky neighbourhood where Ms. Sergeyevna lived remained in economic free fall, home to miners and factory workers whose mines and factories had closed in the 1990s.

Mr. Nayem bemoans, as many Russian-speaking Ukrainians do, that the new leaders – rather than flying out to Donetsk to hear and address local concerns – spent their first hours in power voting to repeal a law that Mr. Yanukovych’s government had introduced giving the Russian language special status in parts of eastern and southern Ukraine.

Oleksandr Turchynov, acting as president after Mr. Yanukovych’s ouster, didn’t sign the new law, but many in Donetsk and Lugansk point to that act by parliament as the moment when Ukraine’s political divide became a chasm.

‘I told him to come with me’

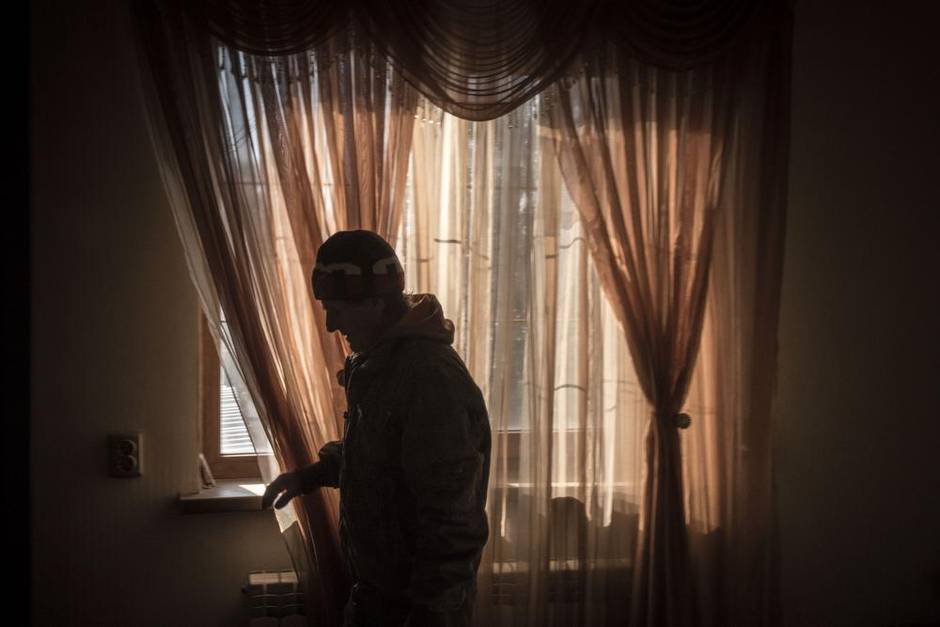

Valentina Ivanova didn’t know what scared her more: the fact that she had been trapped in her car for almost two days as artillery fire slammed into the road behind her, or the idea that her two young boys were witnessing it all. The Russian border they had driven toward after fleeing battle-scarred Donetsk was closed, and the Ukrainian military checkpoint they had just driven through was now ablaze. But Ms. Ivanova’s biggest worry was that she had run out of the food she had packed for her two sons.

“If my children started to cry, it would have broken my brain,” the 36-year-old says, exhaling heavily as she relives the moment. But 13-year-old Sasha and six-year-old Saveli saw the look on their mother’s face and kept calm. “Normally, my kids complain when they have to wait, but they understood how serious the situation was. They were tough. They manned up.”

Ms. Ivanova and her children fled Donetsk in June, shortly after the first outbreak of fighting in the city centre, near the main train station. Even before that, she had been questioning how long she could stay. She was the manager of a firm that installed doors and windows, but no one in Donetsk was interested in building anything when they knew a rocket could knock it all down the next day.

Valentina Ivanova

Age: 36

Why she left: Valentina and her two children left in June, after an artillery shell hit School No. 33 in Donetsk, right next to her son’s School No. 32.

What life’s like now: Valentina is well-off as refugees go, but longs to return to Donetsk. She says she won’t, though, until Ukrainian troops have completely withdrawn from the region.

Current location: She lives with relatives and runs a liquor store in Russian city of Rostov-on-Don.

Current location: She lives with relatives and runs a liquor store in Russian city of Rostov-on-Don.

“I'm sitting on packed luggage because I can't get used to living in a different city. I still dream that I'm there. I fall asleep so that I can return to Donetsk. It's depressing. If I was alone, I could just go back and live off potatoes. But I have to feed my children.” – Valentina Ivanova

Ms. Ivanova and her children now live in the southern Russian city of Rostov-on-Don, where she has found a job working the counter at a liquor store. The salary is decent, she says, but is eaten up quickly by a cost of living that’s three times higher than what it was in Donetsk before the war. Memories of home – just 200 kilometres away – are hard to shake, especially since her father remains in Donetsk, refusing to leave their house in the Kirovsky neighbourhood even though most stores have long since closed, and there are few neighbours left for him to talk to.

“I told him to come with me, but these old guys don’t want to leave the nest,” she says. “Dad’s there with two dogs, a cat and a turtle, so when he makes kasha [buckwheat porridge] it’s for all of them. It’s hard for him to leave because he’s scared he’ll never come back.”

It’s a fear she understands: Ms. Ivanova desperately wants to return home, but has vowed she won’t until there’s real peace in Donetsk. She dismisses the September ceasefire deal between Kiev and the rebels as insufficient. She wants to see the Ukrainian army withdraw from the entire region. “I’m sitting on packed luggage because I can’t get used to living in a different city,” she sighs. (Sitting on packed luggage is a Russian tradition, done for good luck before every long trip.) “I still dream that I’m there. I fall asleep so that I can return to Donetsk.”

The generation left behind

Valentina’s father, Vladimir Ivanov, walks through the Kirovsky neighbourhood he stayed in, pointing at the places where the war has come closest. The bus stop near his house has been strafed by gunfire. His neighbour’s yard has had a divot taken from it by an artillery shell that landed this summer without exploding. The playground of School No. 33, beside his grandson’s School No. 32, is a scorched mess. A shell landed there, too – the final straw that made Valentina decide to leave.

As Mr. Ivanov walks along the rubbish-covered rail track behind his home, the wiry 70-year-old doesn’t flinch or look up as gunfire crackles in the distance – the next neighbourhood south, Petrovsky, is one of the rebel front lines – though he, like many in Donetsk, is now an expert in distinguishing between the different sounds of larger munitions.

“That’s just artillery,” he shouts over his shoulder, after a dull thud is heard in the distance. “The Grads are louder,” he adds, referring to the multiple-launch rockets that both sides use with abandon.

The three-floor home that Mr. Ivanov shared with Valentina and her children is still intact, though you get the sense that no one has tidied it since his daughter and grandchildren fled to Russia. “We live on an island,” he says of the audible fighting outside. “Everything around us, 100 metres from here, 200 metres from here, has been hit.”

Mr. Ivanov, who built the family’s home on a dirt road known as Daryalskaya Street, says he never considered following his family out of Donetsk. Like many of the older generation – who now make up the majority of those remaining in the city – he shares the separatists’ nostalgia for the Soviet Union, and cleaves to their Sovietized version of history.

To him, the war between east and west Ukraine started not with the Maidan, but as far back as the Second World War, when Ukrainian nationalists briefly fought alongside the invading Nazis against the Red Army, hoping to win their independence from the Soviet Union.

That conflict is the background history of today’s war in eastern Ukraine; People there grew up with the narrative that the Ukrainian Patriotic Army were as fascist as the Nazis – dangerous traitors who had turned on their Soviet motherland. In the west of Ukraine, however, the UPA are heroes. Little difference is seen between Nazi Germany’s short occupation of their country and Russia’s much longer stay.

Two different histories

Ukraine’s split is often portrayed as pitting the country’s Ukrainian-speaking majority against its Russian-speaking minority, or the west of the country against its east. But in reality, this is a war between those who remember the Soviet past with nostalgia and pride – and who wish the empire still stood – and those who can no longer bear its lingering influence.

The Maidan and the war in Donetsk and Lugansk are just the latest skirmishes in this long and often-violent clash over history. It’s an angry argument about whose grandfathers were on the right side of the Second World War, when Hitler fought Stalin in Ukraine.

Ukraine suffered badly under Soviet rule – targeted for mass deportations, and victim of the Stalin-era famine of the 1930s that killed millions – and most in the centre and west of the country celebrated the fall of the USSR in 1991. But in the eastern Ukraine and Crimea, the Soviet era is remembered more fondly. Donetsk and Lugansk were models of Soviet industrialization, cities where workers could earn extra salaries and live comparatively well, even as Stalin and his successors waged a deadly policy war against the countryside and the rural Ukrainian “peasants” Stalin detested. Crimea, meanwhile, was a favoured resort destination, a retirement area for senior communists and military officers.

“There are two different histories. And the mentalities of the people of [Donetsk and Lugansk] and people of western Ukraine are totally different,” says Yevgeny Denisenko, the former director of the Donetsk Regional History Museum – an institution that told only the Soviet version of that tale. (The museum itself is a casualty of this latest war, struck at least nine times by artillery fire this summer.) He says the Soviet take is the correct one, while the narrative taught in western Ukraine is anti-Russian propaganda.

There’s little middle ground in this debate. In March, the postrevolutionary government in Kiev appointed Volodymyr Vyatrovich to head the Institute of National Memory, effectively making him Ukraine’s chief historian. Mr. Vyatrovich says that his task is not to find a common narrative on which east and west Ukraine can agree, but to take on the “Soviet myths” that still linger in the memories of many Russian-speakers. He wants to do that by making sure a Ukraine-centred history is taught to the next generation.

Convincing the older, Sovietized residents of Crimea and eastern Ukraine that everything they believe in is wrong may prove impossible, Mr. Vyatrovich acknowledges. But he holds out hope that their new lives in territories appended to Vladimir Putin’s Russia may cause residents of Donetsk, Lugansk and Crimea to re-examine their memories and beliefs. “They will now be returned to the Soviet past, and they will see it was not so radiant as in their memories,” he says. “Russia, I think, will be the factor that will make people reconsider the Soviet past, and make them again want to be part of Ukraine.”

Reconsidering, too late

Time and distance have indeed given Ms. Sergeyevna a new perspective on her homeland. She left Donetsk cursing the revolution in Kiev and the Ukrainian army’s siege of her city. Growing up, she had always seen herself as a Russian; when the Maidan revolution erupted, she thought her region’s culture – and her even right to speak Russian – were under threat. She’s still angry at the “fascists” who have taken power in Kiev, but after her long journey to the Russian Far East, and her frustrations there, she now wonders if she was wrong about her own identity. She has discovered – perhaps too late – that she has a different mindset from that of the Russians she now lives among.

“Khabarovsk is a beautiful city, and it’s full of Russian people,” she says, strolling along the bank of the Amur River, which separates Russia from China. In her bright red coat, she stands out from the locals, who prefer darker tones.

“We’re different than they are,” she says finally. “Donetsk in the last few years had become a European city. People here are more old-style and closed-minded.”

She was, unknowingly, paraphrasing some of the most oft-spoken words of the Maidan revolution. It’s a revelation that – had she made it a year ago – might have given her a different perspective on the uprising in Kiev, and perhaps all that has happened since.

But now, she fears, there’s too much water under the bridge. Too many hostile words have been spoken. Too many people have died. The war will rumble on indefinitely, she believes, and the Donetsk and the Ukraine she knew will never again resemble their former selves. “I never realized I was a patriot. Now I realize how much I loved my homeland and my city, and how sad I am at its being destroyed.”

Mark MacKinnon is The Globe’s senior international correspondent.

X,Y,ID_1,NAME_1 31.378328858094676,49.153558903279234,3136,Cherkasy 32.016707296087681,51.34716208515983,3137,Chernihiv 25.973836396356599,48.271164610068624,3138,Chernivtsi 34.388609711670057,45.330451910272473,3139,Crimea 34.775900351719848,48.29462169531126,3140,Dnipropetrovsk 37.668993961472445,48.046552630433993,3141,Donetsk 24.609055952345802,48.706501208551956,3142,Ivano-Frankivsk 36.514405798473909,49.612760836541064,3143,Kharkiv 33.578941734235755,46.653135180833445,3144,Kherson 26.93030385923543,49.50902198943249,3145,Khmelnytskyy 30.310104588696888,49.832024341409678,3146,Kiev 30.55057278600464,50.447518903135247,3147,Kiev city 32.107160638662265,48.460814319201603,3148,Kirovograd 39.02668770925947,48.985940195122708,3149,Lugansk 23.92120209727063,49.724836135508525,3150,Lviv 31.791100953838335,47.444446757189525,3151,Mykolaiv 30.314507520777273,47.027252739829997,3152,Odessa 33.811322313817783,49.71359547724721,3153,Poltava 26.581870355996777,50.974324710707961,3154,Rivne 33.55265298123382,44.562084144875534,3155,Sevastopol 33.90124749268513,51.071756773791009,3156,Sumy 25.64000541740155,49.002562470039477,3157,Ternopil 23.280585001775922,48.355847637132354,3158,Transcarpathia 28.692086843932501,48.926545902572592,3159,Vinnytsya 24.883489165545054,51.202858252307259,3160,Volyn 35.699752778562782,47.239233458551418,3161,Zaporizhzhya 28.484557276200388,50.642611699952027,3162,Zhytomyr 38.02668770925947,50.485940195122708,0,Russia 28.814507520777273,47.027252739829997,0,Moldova 25.814507520777273,47.027252739829997,0,Romania 22.92120209727063,50.724836135508525,0,Poland 21.780585001775922,47.955847637132354,0,Hungary 21.680585001775922,48.855847637132354,0,Slovakia 28.484557276200388,51.942611699952027,0,Belarus

PlaceID,IDP Crimea,IDP East,IDP Total 3136,265,7803,8068 3137,552,7410,7962 3138,357,1786,2143 3139,0,0,17000 3140,481,41441,41922 3141,61,72826,72887 3142,297,2358,2655 3143,898,116290,117188 3144,684,6755,7439 3145,492,3544,4036 3146,1217,15754,16971 3147,4665,34382,39047 3148,394,8272,8666 3149,,30120,30120 3150,2721,6311,9032 3151,1277,5937,7214 3152,2043,17740,19783 3153,530,14843,15373 3154,312,2269,2581 3155,0,0,0 3156,210,9350,9560 3157,283,1565,1848 3158,236,2416,2652 3159,524,6403,6927 3160,229,1709,1938 3161,522,48005,48527 3162,251,5256,5507

PlaceID,Asylum,Other RS,229409,215486 BO,601,59637 PL,2043,25816 LO,15,0 HU,36,5583 MD,127,5344 RO,29,1502