19 minutes

19 minutes

Aye, a MacKinnon. So you’re one of them, are you?”

I don’t have much experience being “one of them.” I’ve travelled to many places where the concept of “us” and “them” has ripped families – and countries – apart. But I am a spectator, a witness. Even at home, watching the seismic Quebec referendum in 1995 on an oversized TV set at my university’s pub felt like watching a sporting event instead of a nation on the verge of breaking in two. I cheered each time the “Non” side gained a fraction of a percentage point, and gasped when “our” lead shrank, but privately I was jealous of the young nationalists I knew in the Parti Québécois. They had a cause. Something to believe in. Something I lacked growing up in the comfortable numbness of suburban anglophone Canada.

But now in faraway Scotland, I’m immediately recognized – by a man in a Glasgow church with an accent so thick his Rs rumble like an old car starting in winter – as “one of them.”

My name adorns hotels and war monuments from Glasgow to the Isle of Skye. And the history that has led to next week’s referendum on leaving the United Kingdom is interwoven with that of my family. My ancestors died fighting for Scottish independence, most recently with Charles Edward Stuart, better known as Bonnie Prince Charlie – the “young pretender” to the British throne who led them to disaster at Culloden. Now, their cause is within “my” people’s grasp.

Of course, I’m not quite a participant – only those who have lived in Scotland for the past five years may cast a ballot on Thursday. But wherever I go in Scotland I am inevitably asked: “How would you vote, if you could?”

I decided that, before answering, I need to better understand the land my ancestors left so long ago, and perhaps a little of what it means to be Scottish today – as well as what’s at stake in next week’s crucial vote.

My starting point is the story on the back of a whisky bottle.

Haggis was served. I avoided it

While growing up in Ottawa, being of Scottish descent meant little to me.

I felt more in touch with my mother’s Irish side and my grandmother’s French ancestry than with the traditions associated with my family’s name. Haggis was served at my father’s 50th birthday party, but I avoided eating it after hearing what it was made of – sheep’s innards.

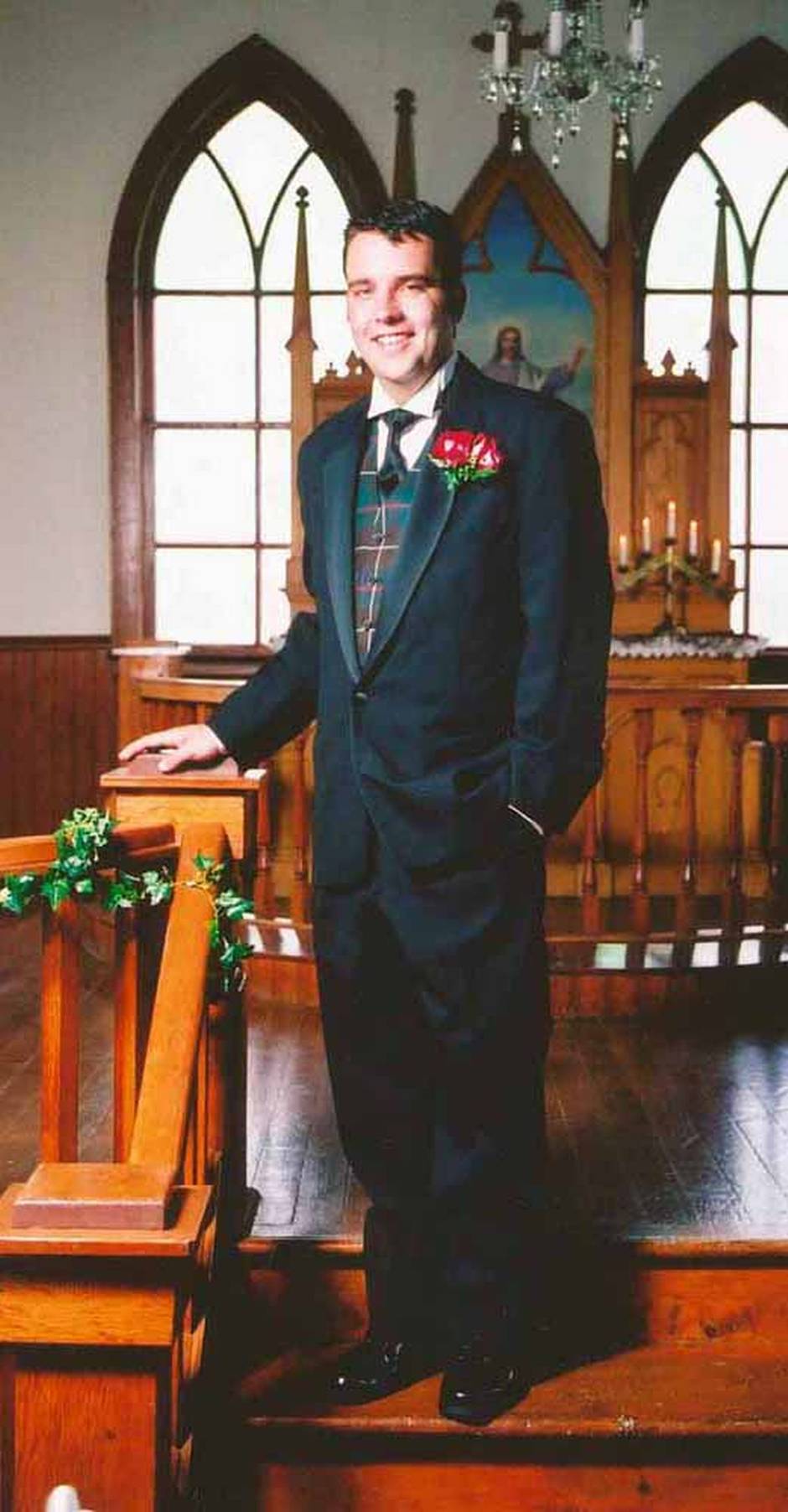

Being Scottish mainly meant having to correct misspellings – Mckinnon is the most common, although I’ve also received mail for Mr. McCannon and Mr. McSkimming – and token gestures such as wearing a vest with our clan’s “hunting tartan” on my wedding day.

There was also Drambuie: I don’t remember the first time I tried the honey-sweetened take on Scotch, and I’m not sure it ranks in the pantheon of great whiskys, but for years my favourite bar trick was to spin the dark red bottle around and proudly read out my family history to my drinking companions.

“When Bonnie Prince Charlie came to Scotland in 1745 to make his gallant but unsuccessful attempt to regain the throne of his ancestors, he presented the recipe to a MacKinnon of Skye as a reward for his services,” I’d pronounce, not really knowing what or where Skye was (this was before smartphones and Wikipedia). “The secret of its preparation has remained with the MacKinnon family, and the manufacture has been carried on by successive generations to this day.”

That was it. A tartan, some dodged haggis and the Drambuie story. Oh, and a fridge magnet with our clan motto: “Fortune favours the brave.”

I suspect that I’m far from alone in this experience. The last census found there were 4.7 million Canadians of Scottish descent, meaning we make up just over 15 per cent of the population. History books are replete with the contributions of Scottish Canadians – from Sir John A. Macdonald, William Lyon Mackenzie, Alexander Graham Bell and Tommy Douglas (all born in Scotland) to Kim Campbell, Bob Rae and Beverly McLaughlin (all of Scottish descent) – so “we” have made our mark.

But we’ve done so quietly. There’s a Little Italy, a Chinatown and a prominent Irish pub in most Canadian cities, but until I visited Edinburgh for the first time 15 years ago, I’d never seen the Scottish flag, the Saltire, hanging in public.

Years later, when I was posted to Jerusalem as a Globe and Mail correspondent, I became fascinated with the way Jews were judged by how connected they were to their land and their culture. Never been to Israel? You’re “a bad Jew.”

But I had never made the typical expat pilgrimage (we’re known here as “tartan turkeys”) to play the bagpipes or try on a kilt. I was, by anyone’s standards, a bad Scot.

This journey turns to be one of constant surprises, beginning with the fact that, until I started planning it, I didn’t realize that I had a chief – one “Anne MacKinnon of MacKinnon.”

No need for a Clarity Act

The first stop on my quest is Edinburgh, and I expect the capital to be a hub of activity and debate on the eve of such a crucial moment in history.

The question that voters must answer is beautifully clear: “Should Scotland be an independent country?” There will be no echoes of Quebec’s anxiety over what “sovereignty association” really means. No need for a Clarity Act. But there would still be pandemonium after a Yes vote.

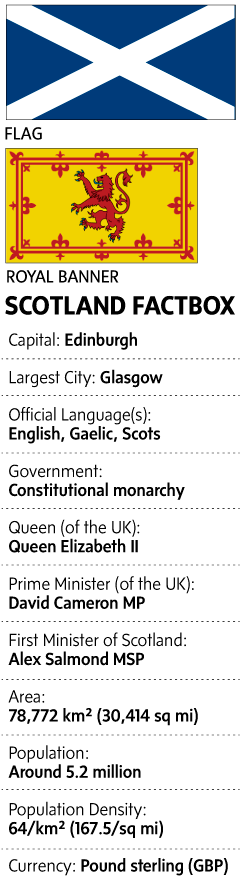

By most standards, Scotland has done well in the 307 years since the Acts of Union were signed joining it to England and Wales in a newly named Great Britain.

Although at one time considered something of a fiscal basket case, Scotland today would rank in the top half of the 34 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development economies in terms of gross domestic product per capita – at $39,600 in 2012, almost $4,000 higher than the rest of Britain.

Scots complain about being governed poorly by the English in faraway London, but two of the past three prime ministers, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair, were born in Scotland. And while David Cameron is widely reviled here – his Conservatives won just one of Scotland’s 59 seats in the last general election – his name also reveals his Scottish roots.

Scotland already has some independence within the union. It has always had its own legal system, and a 1997 referendum created a Scottish parliament in Edinburgh with broad autonomy and taxation powers. But foreign affairs, defence, social security, monetary policy and energy – particularly controversial because of Scotland’s North Sea oil wealth – are still in the hands of Westminster.

How successful a fully independent Scotland would be depends on unknowables, such as whether it would be smoothly accepted into the European Union (of which Scots are much more fond than the rest of increasingly Euroskeptic Britain), and whether a Scottish government could convince a jilted Britain to create a currency union that would allow Edinburgh to continue using the pound sterling.

A vote for Yes, then, is unquestionably a vote to step away from comfort to plunge into dark waters. But a No vote also would push the Scots somewhere new and uncertain – by unravelling one of their treasured myths, that of a people who would choose “freedom” over all other considerations.

Many outsiders know Scottish history through Braveheart, which tells the story of William Wallace, who united Scotland’s fractious clans in the 13th century to confront the oppressive English. The film is based on history as dodgy as Mel Gibson’s accent, but it does a decent job of capturing Scotland’s sense of itself.

Scots – even many of those who say they will vote No to independence – are obsessed with the idea that the English look down their noses and treat them unfairly. A convincing No vote would deal a body blow to what they call the “Braveheart spirit” here. It would mean that Scots, whose independence was negotiated away by their leaders three centuries ago, now consent to that arrangement.

People in Edinburgh are worried, although only quietly. The debates, so far, are polite and respectful. As I crisscross the city, all I see are a giant orange “You Yes Yet?” poster in the window of a food shop on the famed Royal Mile (beside a picture of a woman responding to No campaign literature: “I smell shite”) and one No sticker (“Proud to be Scots, Delighted to be United”) in the window of a home in the upper-class Inverleith neighbourhood.

Hardly evidence of a nation on the brink.

But the relative calm is misleading, based in part on polls consistently showing the pro-union side comfortably in the lead. (This week the mood suddenly changed when, for the first time, the Yes side crept ahead with 51 per cent.)

No one knows what will happen

Below the surface, opinions are sharply divided, as I find when I arrange to meet three friends at a café (and bicycle repair store) called Ronde. One is a Yes supporter and one No, with the third undecided but leaning to No.

The conversation is raucous at times, the friends trying to talk over each other to make a point. Eventually, the entire café joins the fray. First, the barista goes Yes, and the bicycle mechanic comes out from the back to ask politely that I scribble down his reasons for doing the same. Then his customer – an oil company employee who has come in for a tuneup and a coffee – counters with his arguments for supporting No.

The random gathering becomes an even split, just as the pollsters are finding, when the oil exec is backed by two women who have been swayed by the “Better Together” argument that Scots would suffer financially for going it alone. One projection is a per capita hit of about $2,500 a year (versus the Yes estimate of an $1,800 annual windfall).

“The whole thing about independence is no one knows what will happen,” says Shelagh Atkinson, a fiftysomething visual artist. “I think there’s a lot of fear.”

Robin McBride, the oil man, also fits the No profile: slightly older (55) and substantially better off.

“My concern is that, if we say yes, we’re going to turn in on ourselves,” he says. “We can subdivide and subdivide until I put a sign on my gate that says you have to pay to get in.”

The other males, though, are typical of the Yes camp – two of them working class (one argues that Scotland, once free of the Conservative governments repeatedly foisted on it by England, would build a Scandinavian-style social democracy) and all swayed by the emotional pull of independence.

“It’s a matter of faith,” says Finbar Lockhart, the 21-year-old barista. “You just have to decide you’re willing to take the leap.”

And what, I ask, does it mean to be Scottish in 2014?

The question sparks long silences from both sides. “They say you’re Scottish if you like haggis and Irn-Bru,” Mr. Lockhart finally offers, referring to the dish I once refused to eat (and still don’t much like) and Scotland’s electric-orange soft drink.

“That’s the jokey answer. But I guess you’re Scottish if you feel like it’s home.”

I lost my clan chief

Home, haggis and Irn-Bru, couldn’t keep our clan chief in Scotland.

I first heard the rumblings via the clan’s (members-only) page on Facebook that Anne MacKinnon of MacKinnon, who inherited her post from her father, Neil, is an absentee chief. In fact, no one seems to know where she is. I find a street address – in Somerset, in western England, of all places – but no phone number or e-mail address.

I write to the Standing Committee of Scottish Chiefs (yes, there is one) and get this disheartening reply: “I am afraid Anne MacKinnon is not on the standing council by her own volition. Nor does she have much to do with the MacKinnons.”

The closest thing to a replacement I can find is Gerald McKinnon, the “Representative of the Clan MacKinnon of MacKinnon” – a title bestowed on him by Anne’s father. But even he now lives in Victoria, and tells me he too has failed to make contact with our chief.

“It quickly became obvious that she did not have the same interest in clan affairs as her father or grandfather did. Our policy then has been to respect her privacy.”

I’ve lost my clan chief almost as soon as I knew I had one, but there is still the Drambuie bottle. Which leads me, magically, oddly, to the great-grandson of George Brown – the same man who became a father of Confederation after launching a little newspaper called The Globe in Toronto.

Jonathan Brown is an Oxford history graduate who dabbled in farming before becoming the Drambuie Liquor Company’s “brand heritage director” 15 years ago (even though his great-grandfather was an ardent advocate of prohibition).

He assures me that the story on the bottle is true. Mostly. As far as anyone knows.

The MacKinnons were loyal Jacobites, meaning they supported the claim of (the ousted Catholic) King James II and his descendants to rule England, Scotland and Ireland. They had, indeed, joined Bonnie Prince Charlie when he arrived from France in 1745 to seek his grandfather’s throne, and marched with him until his final, terrible defeat at Culloden the following year. Fortunate to miss the battle itself – the MacKinnon fighters were sent to find food for the prince’s starving army – the clan later sheltered the fugitive Charlie in a cave on the Isle of Skye, its stronghold. His thanks was to share one of his few remaining possessions, the recipe for his personal whisky.

Little of that can be proved, Mr. Brown acknowledges as we chat in his kitchen over tea, biscuits and, of course, glasses of 15-year-old Drambuie. But it is known that, more than a century later, a MacKinnon came across a scrap of paper with a recipe that fit the legend. He took it to the Broadford Hotel on Skye, where the owner started serving it to patrons (setting off a decades-long feud over who deserved the credit – and the royalties).

The hotel in Broadford is still standing. Maybe there are answers there. I need to head north.

Alcohol and politics don’t mix

‘No indy talk at bar’ But first I stop in Glasgow, an hour’s train ride west of Edinburgh – and a vast change from the capital’s fairytale Scotland of castles and kilted bagpipers on every corner.

Glasgow is the country’s complex and divided soul, a gritty place where voting patterns often mirror soccer affiliations. Rangers fans have traditionally been Protestants, and usually pro-union, holding Northern Ireland-style “Orange Order” marches (even during this politically charged summer). Celtic fans are usually Catholic, with ancestors who came from Ireland during the potato famine, and are voting yes, or at least telling friends and family they are.

Unlike sterile, polite Edinburgh, here the independence debate is everywhere. The first whisky bar I visit has posted a warning: “No indy talk at bar.”

“It’s okay at the tables,” the bartender explains. “But here at the bar, the staff were getting dragged into the arguments. Politics and alcohol don’t mix.”

The bar is not far (down aptly named Hope Street) from the hub of the entire Yes campaign, a sunken street-front office with walls covered in posters: “Independence, it’s what we all want in life,” one reads. “Scotland is wealthy enough to be a fairer nation,” proclaims another, contrasting the priorities of a “Nordic” Scotland with those of capitalist England.

Stuart McDonald, the campaign’s youthful senior researcher, is in an upbeat mood when we meet. “There’s obviously a chance we can win this,” he says, smiling as we settle into chairs the same blue as the Saltire.

In fact, Yes strategists believe the polls chronically understate their real level of support. Pollsters themselves acknowledge that Yes supporters who are young or working class tend to be underrepresented in surveys.

Nor do polls capture the fact that Yes supporters are generally more passionate – and thus more likely to vote. Throw in the get-out-the-vote capability of First Minister Alex Salmond and the Scottish National Party and there’s plenty of room to shock the world Thursday. (No pollster predicted the SNP would form its majority government in 2011.) That’s what the Yes side is about. Hope and belief.

Not far away, hidden from sight on the cramped fourth floor of an office tower, the Better Together camp is trying to convince Scots to vote with their heads rather than their hearts.

Like their support base, most No staffers seem about 20 years older than those on the Yes side. There are fewer laptops and smartphones here, more piles of paper. The literature attempts to highlight what would be worse if Scotland goes it alone, without being too downbeat.

“There is a concern of sounding too negative,” says Bill Symon, a former newspaper editor whose job is to persuade businesses, which prefer stability to the unknown, to go public with their concerns.

But many companies worry about a backlash. Two No voters from Aberdeen – Scotland’s oil hub and key to its hope of becoming a European energy power – tell me that cars and shops of known union supporters have been vandalized. “There’s a lot of people who are afraid to put up a No sign because they’ll be vilified,” says another No voter, asking not to be identified.

We are almost as Catholic as the Pope

When I start my journey, I reach out to see if my relatives know more than the Drambuie Company about where we are from. No one does. An industrious cousin once tried to retrace our roots and hit a dead end when she discovered our grandfather’s grandfather had left no birth certificate. But one thing we know for certain is that we are almost as Catholic as the Pope.

My late grandfather MacKinnon, who was born in Prince Edward Island, was so devout that he initially didn’t want to attend my wedding (my wife was raised in the United Church of Canada). We got the whole clan on board only by promising to hold a Catholic ceremony a month later.

So when I walk into the austere St. Colomba Church in downtown Glasgow – a sacred place for the MacKinnon clan, with our family coat-of-arms hanging in one room and, in the cathedral itself, a plaque listing the names of the 232 MacKinnons who died in the First World War – I assume it to be a Catholic place of worship.

In fact, it is a Presbyterian Church, and the volunteers who cheerfully give me an on-the-spot tour are astonished to meet a MacKinnon who is Catholic.

Perhaps, they speculate, my ancestors were converted on the way to North America. “When I went to Canada, I found a colony of MacKechnies who were all Catholic too,” says a laughing Donald MacKechnie.

“We were told that on the boat there was a very vigorous Roman Catholic priest. They all left Scotland as Presbyterians, and they all arrived in Canada as Roman Catholics.”

So which side of Glasgow’s great politico-soccer divide would I be on? After a pause, the retired machine-tool designer and member of St. Colomba’s board decides that I’d be a Rangers fan, since all MacKinnons are, but I’d probably have to sit in a special section for those who don’t know the words to No Pope of Rome.

Are my relatives, then, being Protestants and Rangers fans, automatically No voters? Mr. MacKechnie briefly stops chuckling. “This is red-hot Yes country,” he replies. (It is the only time he says “yes” instead of “aye.”)

Scots, he tells me, have suffered under English rule at least as badly as “the Indians” did in North America. “I can’t understand why anybody would think voting no is a good idea.”

When I ask if he knows any No voters who attend St. Colomba, his smile returns. “If there were any, they’d be taken outside and shot.”

Another Yes surprise springs from the considerable effort the campaign has made to separate its case for independence from any narrow, “pure laine” idea of who is or isn’t a Scot.

Anti-immigrant sentiment is scant in Scotland simply because there are few immigrants. A 2011 census found that 96 per cent of residents were white, and 84 per cent identified as Scottish.

Nonetheless, the government’s external affairs minister is one Humza Yousaf, whose mother came from Kenya and father from Pakistan – the latter believing, until he arrived, that Scotland was already independent. Before becoming a politician, the younger Mr. Yousaf worked as a spokesman for Islamic Relief.

“Nobody has a checklist. Nobody says that you have to have red hair or like a certain food or you have to have white skin and blue eyes and your last name has to end in Mac-something,” Mr. Yousaf tells me in his soft Glaswegian accent. “If you want to be Scottish, then that’s fine with me. Come and join the party. The more the merrier.”

In fact, a poll carried out by Awaz FM – a local radio station whose listeners are primarily Scots of South Asian descent – found that 64 per cent of visible minorities planned to vote Yes. Many, including Mr. Yousaf, became nationalists during the Iraq war, which the SNP opposed fiercely and the British government did not.

Where the clans made their final sacrifice

My ancestors had their own reasons to oppose the English so fiercely. Clans from the north of Scotland have always been the first and fastest to rally to the flag of independence. They provided William Wallace with his army in 1297, and 41/2 centuries later stood at Culloden.

Today, Inverness, the highland capital, is still Yes country. Shortly after arriving, I nearly trip over a chalkboard sign in the city centre that’s counting down the days to the referendum.

I want to see where the clans made their final sacrifice for Bonnie Prince Charlie, so I head a half-hour east to a bumpy, overgrown field where 1,500 highlanders died in a hopeless last stand that a competent commander never would have asked his men to make. After the fight, the English set out to extinguish the rebellion for good. Jacobites who lay wounded were bayoneted to death, while those who fled were chased down by cavalry. Clans who rose up were soon stripped of their lands, prompting many families – MacKinnons among them – to leave for good.

“Do you know how long the battle lasted here? Just one hour – the English slaughtered the Scots,” Les Butterworth, my driver to Culloden, tells me.

He is wearing a “No Thanks” button – a rare sight in the highlands. “Ireland’s problem is religion – it boils down to Catholics and Protestants … in Scotland, our problem is history.”

Mr. Butterworth promises that I, as a MacKinnon, will “feel it” – a sense of history, sadness, understanding of whatever it was that brought my Protestant ancestors to rally to a Catholic cause – as soon as I set foot on Culloden.

I stand for nearly an hour among the rocks that mark where clansmen were buried in mass graves. But whatever emotions Mr. Butterworth expects to wash over me never materialize – it all happened so long ago.

Only this revelation hits me: It was because of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s bad military judgment that I was born a Canadian. I am who I am because my ancestors followed a pretender – a charlatan – into battle.

Next, the Drambuie trail finally leads to the Isle of Skye – the place my family is from.

The first building I see on the island: the MacKinnon Family Guest House in the tiny port of Kyleakin. There are no rooms available, but I decide I must at least have dinner there.

“Your name?” the waitress asks. “MacKinnon,” I say, as though delivering the punch line to a joke.

“Party of one?” she continues. “What time?”

I’m not sure what I expected – a hug, the summoning of a piper? – but something more than this.

I cancel the reservation and drive on toward Castle Maol, a small fort that was once the effective seat of the MacKinnon clan, guarding the narrow strait between Skye and the mainland.

The hike up to it is more than worth the effort. Suddenly, I find myself feeling whatever I was supposed to feel at Culloden. Castle Maol is something tangible, something that, but for the twists of history, might have been my father’s, mine, my daughter’s. This is my Braveheart moment. I have come to reclaim my family’s castle.

Except there is nothing left to reclaim, just ruins – three piles of stone, splitting away from each other as if magnets of the same pole. I take a few selfies, climb back down and follow the trail across Skye. After a token stop in the town of Broadford at the hotel where the Drambuie recipe was first tested and tasted, I arrive in another tiny port.

Elgol has a population of 150 – most with my last name, making it the last part of the island that can be reasonably called MacKinnon lands. Not far from away across the soggy grasslands lies the cave where my ancestors hid their prince – and in Elgol, at last, I find a member of my clan who can explain our history.

Neil MacKinnon is a retired teacher and member of the local historical society. When I ask him just who the MacKinnons are, he tells me the story, again, of Bonnie Prince Charlie, Culloden and Drambuie, though in much more detail. But as the tale reaches its conclusion, Neil suddenly drops a bombshell:

A few years back, he took a DNA test as part of a local genealogy project only to find out that we are descendants of a king who ruled in the fourth century – and not in Scotland.

“We have the same ancestry as the O’Neill’s of Northern Ireland,” he says matter-of-factly.

I laugh. I have come all the way “home” to discover that the MacKinnons were once immigrants here, too.

So maybe we are as much Irish as we are Scottish – and maybe less Catholic than I was raised to believe – but I came here with a mission: to make up my own mind about how I would vote next Thursday, if I could.

I have received no guidance from my clan chief, and even our family’s best historian is torn.

“It’s a difficult subject to talk about,” Neil says, looking out the window at the single sheep-clogged lane past his house.

“Scotland could do quite well as an independent country. Even opponents say so; even David Cameron says so. But then what would be the losses in economic terms, in social matters? We’ve been together since 1707. The UK has made its mark in the world. It’s a hard thing to see all that go.”

Like many of the Scots I have met from Edinburgh to Skye, he sees the referendum decision as an argument between his head, which thinks things are fine as they are, and his heart, which proudly beats for Scotland.

I am just as conflicted.

As a journalist, I can see all the holes in Alex Salmond’s arguments. Scotland has done well in Britain. Far from the repressed culture William Wallace fought to preserve, it has all the trappings of nationhood – a parliament with wide powers, a national flag that its athletes compete for at the soccer and rugby world cups – as well as the economic advantages that come with being part of a borderless kingdom of 63 million people, rather than an independent country of just 5.3 million.

I can’t help remembering that, when I was a member of the Ottawa press gallery 15 years ago, I was friends with a few members of the Bloc Québécois. Sometimes, over beer, we’d discuss what it would take to put the “neverendum” behind Canada for good.

One hazy evening, we came to something like an accord: There would be no need for another referendum if Ottawa would grant Quebec the same international status that Scotland had. Let Quebec send its own hockey team to the world championships and wave the fleur-de-lis the way Scots proudly wave their Saltire. Let the world see them as a nation. “Scotland status,” we called it. Distinct society-plus.

Breaking up one of the more successful unions the world has ever known makes no sense. Trouble would follow. Publicly, I would advise against it, but I also realize that, whatever my journalist brain tells me, if handed a ballot in the privacy of a voting booth, I would mark it Yes.

It doesn’t quite make sense, but in my heart, which perhaps still pumps a trickle of highland blood, it feels good to believe in something.

Fortune favours the brave.