Children's toys and messages of thanks surround the grave of Peter Henderson Bryce in Ottawa this past May 29, days after the announcement that unmarked graves were found at the former site of Kamloops Indian Residential School in B.C. Dr. Bryce was a doctor working for the federal government who warned about high death rates of Indigenous children in the schools.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

Crystal Gail Fraser is a Gwichyà Gwich’in scholar and consulting historian with Defining Moments Canada. Tricia Logan is a Métis scholar and head of Research and Engagement at the Residential School History and Dialogue Centre at the University of British Columbia. Neil Orford is a history educator and president of Defining Moments Canada, which will lead a national commemoration about The Bryce Report in 2022.

For most Canadians, the discovery of the unmarked graves of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc and the Cowessess and the Penelakut and Lower Kootenay First Nations was a revelation that triggered widespread grief and shock. For Indigenous communities, however, the traumatic loss of children to the Indian Residential School system has been a fact for more than a century. They have long known that family members went missing or were killed while institutionalized at the schools. These effects of colonialism aren’t a dark chapter now being revealed, but rather the main plot in a narrative that defines Canada.

The archival evidence has been tucked away for decades in federal and church records. Yet long before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission began its work, one civil servant sought to document and publicize the horrific conditions, compiling substantial data demonstrating the unfolding public-health tragedy, dire living conditions and soaring mortality rate of Indigenous children at Indian Residential Schools.

Peter Henderson Bryce, 1899.Courtesy of the Bryce family

Peter Henderson Bryce, a non-Indigenous public-health physician and social reformer, exposed this “national crime” more than a century ago. Appointed chief medical officer of health for the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) in 1904, Bryce began to make detailed submissions to deputy superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott about the conditions he observed.

His analysis could not have been clearer: The schools he investigated in 1907 and again in 1909 reported a mortality rate for children aged 4 to 18 of 40 per cent to 60 per cent, many from tuberculosis. (Although precise data on TB in children at the time was scarce, Bryce estimated that the death rate from tuberculosis among Canada’s native population was 34.7 per 1,000, or about 19 times that of the general non-Indigenous population.) A quarter of all students were known to have died by 1907, with a rate as high as 75 per cent at one school. Bryce confirmed what Indigenous parents and Christian missionaries already knew: that these institutions and the people who worked in them were directly involved in the deaths of thousands of Indigenous children. Colonial attempts to assimilate were in fact genocidal.

Bryce compiled his evidence in what came to be known as “The Bryce Report,” complete with recommendations for government action. Leaked to the media and debated in the House of Commons, Bryce’s work fell on refusing ears. Prime minister Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government enacted few changes. In fact, as the tragedies multiplied over the following decade, conditions deteriorated even further. The schools were poorly built, overcrowded and unsanitary; the Indigenous children malnourished, overworked and abused.

Christian churches operated these schools for profit and their model supported the genocidal efforts of the federal government whose officials willfully ignored the conditions. As Scott wrote in 1910: “It is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habitating so closely in these schools, and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages. But this alone does not justify a change in the policy of this Department, which is being geared towards the final solution of our Indian Problem.”

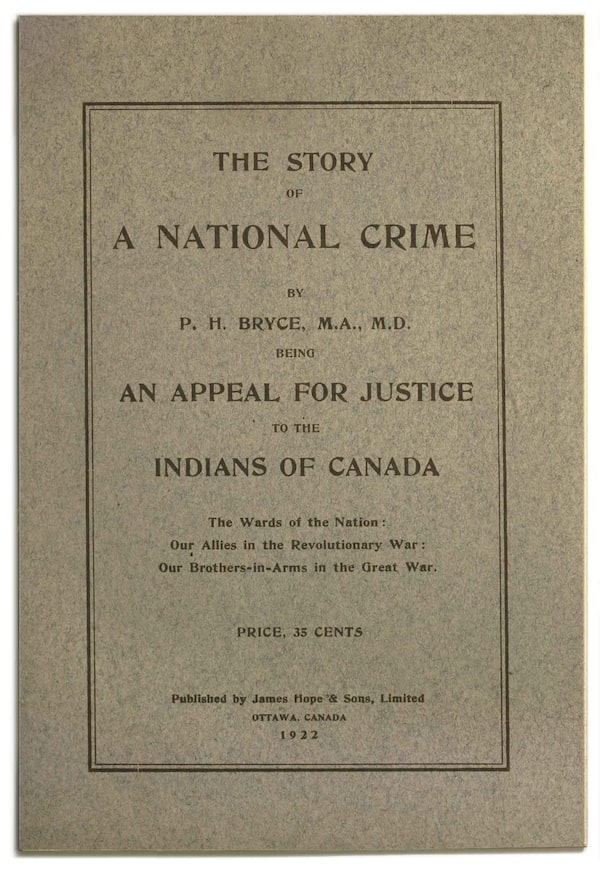

In 1922, Bryce, by then retired from public service, took it upon himself to call out 15 years of government intransigence. He self-published an 18-page pamphlet called “The Story of a National Crime.” Distributed in Ottawa, the publication garnered some attention but soon disappeared from the public imagination, leaving virtually no advocates for institutionalized Indigenous children, except for their parents, who, under the Indian Act, were not allowed to hire legal counsel and could be fined or imprisoned if they refused to let their children attend.

Bryce was neither the first nor the last government inspector or employee who would be prevented from completing their work or silenced for presenting truths that confronted a popular government agenda.

But for the efforts of some contemporary Indigenous and settler scholars, led by McGill University sociologist Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, and the Bryce family, the story of Bryce’s efforts might have been lost. However, the voices of Indigenous families that lost ancestors have been strong and persistent, and it was the unmarked graves of hundreds of Indigenous children that finally made settler Canadians notice.

Given the events of these past months, we felt it is crucial to share Bryce’s words with Canadians and let his warnings speak for themselves.

Dr. Bryce’s pamphlet The Story of a National Crime was published in 1922.

Bryce organized the pamphlet into five sections, each exposing aspects of federal indifference to Indigenous children. The document reminds readers about the data he had first reported and revealed the utter disregard for his findings by government and church authorities. (Note: following the custom of the day, Bryce refers to himself in the third person. Additionally, “boarding schools” refers to the Indian Residential Schools, including Industrial Schools).

p. 3-4: For the first months after the writer’s [Dr. P. H. Bryce] appointment he was much engaged in organizing the medical inspection of immigrants at the sea ports; but he early began the systematic collection of health statistics of the several hundred Indian Bands scattered over Canada. For each year up to 1914 he wrote an annual report on the health of the Indians, published in the Departmental report, and on instructions from the minister made in 1907 a special inspection of thirty-five Indian schools in the three prairie provinces.

This report was published separately; but the recommendations contained in the report were never published and the public knows nothing of them. It contained a brief history of the origin of the Indian Schools, of the sanitary condition of the schools and statistics of the health of the pupils, during the 15 years of their existence. Regarding the health of the pupils, the report states that 24 per cent, of all the pupils which had been in the schools were known to be dead, while of one school on the File Hills reserve, which gave a complete return to date, 75 percent, were dead at the end of the 16 years since the school opened.

Students and family members sit on a hill overlooking Fort Qu'Appelle Indian Residential School near Lebret, Sask., in 1885, a year after it opened. The Roman Catholic Church ran the institution until 1973.Library and Archives Canada

In the introduction, Bryce lays out three objectives: recount the startling findings of the surveys he conducted while visiting 35 residential schools in Western Canada in 1907; restate the seven reforms he had recommended at the time, including proper medical inspection to safeguard against the rampant spread of tuberculosis; and show that Scott was clearly responsible.

p. 4: Briefly the recommendations urged,

(1) Greater school facilities, since only 30 per cent, of the children of school age were in attendance;

(2) That boarding schools with farms attached be established near the home reserves of the pupils;

(3) That the government undertake the complete maintenance and control of the schools, since it had promised by treaty to insure such; and further it was recommended that as the Indians grow in wealth and intelligence they should pay at least part of the cost from their own funds;

(4) That the school studies be those of the curricula of the several Provinces in which the schools are situated, since it was assumed that as the bands would soon become enfranchised and become citizens of the Province they would enter into the common life and duties of a Canadian community;

(5) That in view of the historical and sentimental relations between the Indian schools and the Christian churches the report recommended that the Department provide for the management of the schools, through a Board of Trustees, one appointed from each church and approved by the minister of the Department. Such a board would have its secretary in the Department but would hold regular meetings, establish qualifications for teachers, and oversee the appointments as well as the control of the schools;

(6) That Continuation schools be arranged for on the school farms and that instruction methods similar to those on the File Hills farm colony be developed;

(7) That the health interests of the pupils be guarded by a proper medical inspection and that the local physicians be encouraged through the provision at each school of fresh air methods in the care and treatment of cases of tuberculosis.

Dr. Bryce and his wife, Katherine, in the 1920s.Courtesy of the Bryce family

By 1917, Bryce had been shuffled out of his role as chief medical officer at the Department of Indian Affairs, to a largely ceremonial role in the immigration branch of the Department of the Interior. With wartime censorship and little immigration, yet a desperate need for resources and manpower, Bryce was relentless in his advocacy for a policy that could protect the health and enhance life for Canada’s Indigenous communities.

p. 5: Recommendations, made in this report, on much the same lines as those made in the report of 1907, followed the examination of the 243 children; but owing to the active opposition of Mr. D. C. Scott, and his advice to the then Deputy Minister, no action was taken by the Department to give effect to the recommendations made. This too was in spite of the opinion of Prof. George Adami, Pathologist of McGill University, in reply to a letter of the Deputy Minister asking his opinion regarding the management and conduct of the Indian schools.

Prof. Adami had with the writer examined the children in one of the largest schools and was fully informed as to the actual situation. He stated that it was only after the earnest solicitation of Mr. D. C. Scott that the whole matter of Dr. Bryce’s report was prevented from becoming a matter of critical discussion at the annual meeting of the National Tuberculosis Association in 1910.

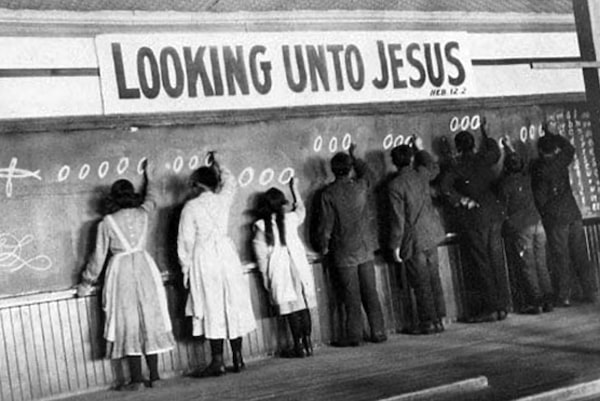

A class practises penmanship at the Red Deer Indian Industrial School in Alberta, circa 1914 to 1919. It was during this period that Dr. Bryce did a comprehensive review of the Indigenous policies of prime minister Sir Robert Borden.United Church of Canada Archives

In a period immediately after the First World War, there was a Canada-wide concern for rates of death, birth and what was referred to at the time as “manpower.” Bryce recounts a comprehensive study he conducted for the DIA in 1917 in which he detailed the devastating effects of the Borden government’s Indian Policy, concluding that “depopulation” was endemic among “Indian communities.” Noting the contributions that Indigenous communities had made to Canada’s war effort as well as the national economy, his analysis shifts to damning conclusions based on his analysis of demographic trends.

Through his study of rates of death at residential schools and his medical research, he described an interconnected system of social control. He knew. He knew life expectancies of Indigenous peoples were part of a broader-reaching system or trend, tied to the residential school system. Morbidity and mortality of Indigenous communities became an acute concern for Bryce, and his calls for support to end the inequities would be repeated through several reports, correspondence and school administration records.

p. 8-9: In 1917, the writer [Dr. Bryce] prepared, at the request of the Conservative Commission, a pamphlet on “The Conservation of Manpower of Canada,” which dealt with the broad problems of health which so vitally affect the man power of a nation. The large demand for this pamphlet led to the preparation of a similar study on “The Conservation of the Man Power of the Indian Population of Canada” which had already supplied over 2000 volunteer soldiers for the Empire. For obvious reasons this memorandum was not published, but was placed in the hands of a minister of the Crown in 1918, in order that all the facts might be made known to the Government.

This memorandum began by pointing out that in 1916, 4,862,303 acres were including in the Indian reserves and that 73,716 acres were then under cultivation; that while the total per capital income for farm crops in that year in all Canada was $100 that from the Indian reserves was $69, while it was only $40 for Nova Scotia. It is thus obvious that from the lowest standard of wealth producers the Indian population of Canada was already a matter of much importance to the State.

Flags and solar lights mark the site of unmarked graves in a field on the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan this past June.GEOFF ROBINS/AFP via Getty Images

In these memoranda presented to the federal government but never published, Bryce projected how high the First Nations or Indigenous population should be, given all evidence for typical population growth. In contrast to the demographic data, he notes this considerable decrease in the population of Indigenous communities and he indicates that it was likely owing to high rates of disease causing a disproportionate death rate.

p. 9: From the statistics given in the “Man Power” pamphlet it was made plain that instead of the normal increase in the Indian population being 1.5 per cent, per annum as given for the white population, there had been between 1904 and 1917 an actual decrease in the Indian population in the age period over twenty years of 1,639 persons whereas a normal increase would have added 20,000 population in the 13 years. The comparisons showed that the loss was almost wholly due to a high death rate since, though incomplete, the Indian birth rate was 27 per thousand or higher than the average for the whole white population.

In the pamphlet, Bryce took care to demonstrate that his own department was deliberately misleading Canadians, despite documented evidence to the contrary.

p. 10: [F]rom the following extract from the Deputy Minister’s Annual Report for 1917: “The Indian population does not vary much from year to year.” How misleading this statement is may be judged from the fact that between 1906 and 1917 in the age periods over 20 year in every Province but two the Indians had decreased in population by a total of 2,632 deaths.

Inuit children await medical examination aboard a hospital ship at Coral Harbour (now Salliq, Nunavut) in 1951. Tuberculosis was a persistent threat in the North throughout the 20th century.Wilfrid Doucette / National Film Board of Canada / Library and Archives Canada

Before joining the DIA, Bryce had spent much of his career in public health. His report, published only four years after the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, returns to the public-health danger he felt most seriously threatened Indigenous people – tuberculosis. In this passage, he levelled his boldest attack against the government. Accusing the DIA of “criminal disregard,” he cites statistics showing how tuberculosis had been allowed to spread “almost unchecked” among the Indigenous population.

p. 13: [W]e find a sum of only $10.000 has been annually placed in the estimates to control tuberculosis amongst 105,000 Indians scattered over Canada in over 300 bands, while the City of Ottawa, with about the same population and having three general hospitals spent thereon $342,860.54 in 1919 of which $33,364.70 is devoted to tuberculous patients alone.

p. 14: The degree and extent of this criminal disregard for the treaty pledges to guard the welfare of the Indian wards of the nation may be gauged [sic] from the facts once more brought out at the meeting of the National Tuberculosis Association at its annual meeting held in Ottawa on March 17th, 1922. The superintendent of the Qu’Appelle Sanatorium, Sask., gave there the results of a special study of 1575 children of school age in which advantage was taken of the most modern scientific methods. Of these 175 were Indian children, and it is very remarkable that the fact given that some 93 per cent, of these showed evidence of tuberculous infection coincides completely with the work done by Dr. Lafferty and the writer [Dr. P. Bryce] in the Alberta Indian schools in 1909.

It is indeed pitiable that during the thirteen years since then this trail of disease and death has gone on almost unchecked by any serious efforts on the part of the Department of Indian Affairs, placed by the [British North America] Act especially in charge of our Indian population, and that a Provincial Tuberculosis Commission now considers it to be its duty to publish the facts regarding these children living within its own Province.

Cutouts of orange T-shirts hang on a fence outside the former Kamloops Indian Residential School on July 15, the day the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation released a report outlining the findings of a search for unmarked graves.Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press

Bryce’s 1922 pamphlet came out at the same time children were returning home from residential schools to tell their parents about classmates dying, abuse, neglect, malnutrition and punishing conditions.

From the time the school system first opened, in fact, students and parents were reporting the abuses, neglect, disease and death at the schools to the churches, clergy members, Indian Agents, RCMP, doctors, nurses or anyone they thought could affect change. Children were the first ones to share the harsh truths about the life and conditions at residential schools. As with Bryce’s work, their evidence was often ignored; the truth, buried.

These reports have echoed through the generations. A painful awareness of the connection between this data and the lives lived echoes even louder. The numbers, what’s more, represent only the recorded deaths. While each statistic represents a family, a life and a community, it is critical to note they are also just estimates.

There’s an important connection between Bryce’s reports and the medical pathology reports about Indigenous health that we see today. First Nation, Métis and Inuit peoples do not need to read these documents to know the results, since they live those negative health and mortality statistics every day. It’s a consistent message the government of Canada has been receiving clearly and continually for well over a century.

Justin Tang/The Canadian Press