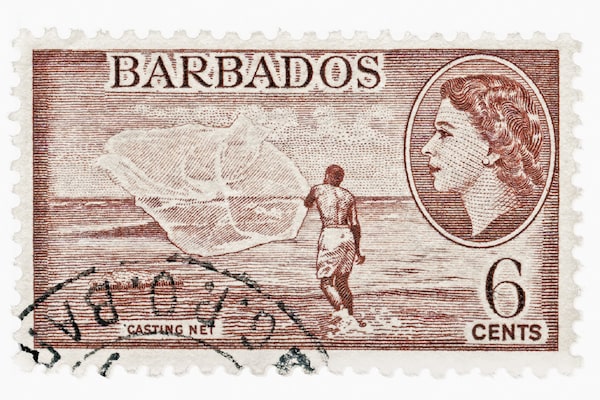

Barbados postage stamp from 1953 featuring Queen Elizabeth II in the year of her coronationPUBLIC DOMAIN

Adnan Khan is the author of the novel There Has to Be a Knife.

When I came to Canada from Saudi Arabia as a child in the winter of 1993, I was surprised by many things: signage written in two languages, the depth of cold, and the weak sleet on the ground (Hollywood had promised me fluffy snow – this was a major betrayal). No one had mentioned the Queen to me, or that her image would appear non-stop in classrooms, on TV and even in our pockets, her portrait on our bills and coins. I was 7 and endlessly curious about this ubiquitous figure, prim and matronly, absolutely distant, but also everywhere. I learned if you laid enough coins down you could trace her age throughout the years, and admire the small fluctuations of her regal bearing and steady profile, forever glancing right.

At the time, Princess Diana was also in the news – her dissolving marriage to Prince Charles, her outfits and her various affairs piqued even the interest of a child mostly concerned in finding the perfect composition of snowball. I was surprised to find the grip of the monarchy so strong in Canada, as the West was portrayed as the “new” land full of fresh ideologies – so why was Canada clinging to its past? As I grew older, I understood in a vague way that the relationship between the Commonwealth countries and Britain was difficult, but it seemed bizarre to me that Canada would so willingly serve as an appendage to the Royal Family. In Grade 6, when I attended my citizenship ceremony, I balked at having to pledge allegiance to the Queen and mumbled my way through the incantation, worried about what I was binding myself to. The dissonance in the hall was palatable – a space full of migrants, many coming from countries with long, disastrous legacies of British colonialism, asked once again for this corrupt loyalty. It seemed unfair, like a trick being played on us.

Barbados, a former British colony, recently renounced the Queen as head of state. It seems due time for Canada to take this step. Many of the immigrants in Canada – many who make up the work forces deemed “essential services” – can easily trace our lineages back to the destruction the British Empire wrought. My parents were both born within seven years of Indian Independence, and it’s not difficult to track the migratory patterns and search for economic stability in their families to the havoc caused by the British. In 2018, Indian economist Utsa Patnaik published a study determining that over two centuries the British plundered as much as US$45-trillion from India; this historical weight of the crown still presses down on Indians. Certainly, the economic shambles the British left India in is what led to my family’s migratory arc from India, to Saudi Arabia, to Canada. This is a journey replicated by many new Canadians from former colonies, and in contrast with white Canadians settled for many generations, for whom a full reckoning of history is still not encouraged.

A poll released this year shows the Queen’s approval rating in Canada is 81 per cent – up 8 per cent from 2010. While 62 per cent of Canadians agree the role should be informal, we cannot say that it has been recently: from the 2008 prorogation of Parliament, to the 2011 decision to restore the “Royal” moniker to our navy and air force, Canada is not immune from the occasional flex of colonial power. Still, the same Ipsos poll sparks optimism, as it reports 53 per cent of Canadians believe the grip of the monarchy should end with the current Queen.

The Queen’s power largely remains in her strength as an icon; her image is, of course, on our money. A celebration of the monarchy is a celebration of whitewashed British glory. It’s tempting, in a time of fluctuating ideologies, to clench harder on to an image of former grandeur, but to do so risks further turning our back on our bedrock of multiculturalism. The strength of this iconography is perhaps what new Conservative leader Erin O’Toole hints at with the slogan, “Take Canada Back,” and points to the struggle Canada is having with reconciling an immigrant population that is demanding more say in industry, more representation in government, and access to the cultural forces that shape Canadian thinking. Immigrants are unveiling a core hypocrisy of anti-immigrant sentiment – come here for your labour, but leave no cultural mark.

We’ve started seeing the physical manifestation of these icons torn down: statues of Edward Colston in Bristol, England; Jefferson Davis in Richmond, Va.; and John A. Macdonald in Montreal. As the movement ebbs and flows, it seems like a worthy time for Canada to embrace symbolism beyond the monarchy, toward something that truly embraces the pluralism to which we are always gesturing, but never fully embracing. This kind of image-making is a fundamental project of nation building, as it asks how we wish to see ourselves, and therefore, make ourselves. As the American empire threatens to crumble under its embrace of regressive, Trumpian politics, there is a lesson to be learned about looking back while trying to move forward.

The difficulty and scale of this task shouldn’t be misunderstood. It asks Canadians to fundamentally alter their approach to history and their belief in how this country was formed – with the first step a reckoning with Indigenous communities. It calls for a kind of understanding that leaves room for celebration while acknowledging that you simply cannot ask immigrants to bolster your work force without allowing them a say in how the country is imagined. The monarchy’s reputation is of their own doing and their eventual disappearance from Canadian public life should be celebrated and fast-tracked, not mourned.

The celebration of the monarchy is a commemoration of a heritage in which subjugation of the many for the sake of the few was the primary mode of operation. The ramifications of this are still felt by billions across the globe and by Canadians today. It is not a weakness for a country to acknowledge the harm the past has done. As the Queen’s reign comes to a close, it’s embarrassing to imagine Canada celebrating a successor, or to even ask why we might. While fully establishing Canada as a republic is a daunting task, it feels necessary for a country to truly embrace its future.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.