Anne Frank.Reuters

Allan Levine is a historian and the author of Fugitives of the Forest: The Heroic Story of Jewish Resistance and Survival During the Second World War. His most recent book is Details Are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder.

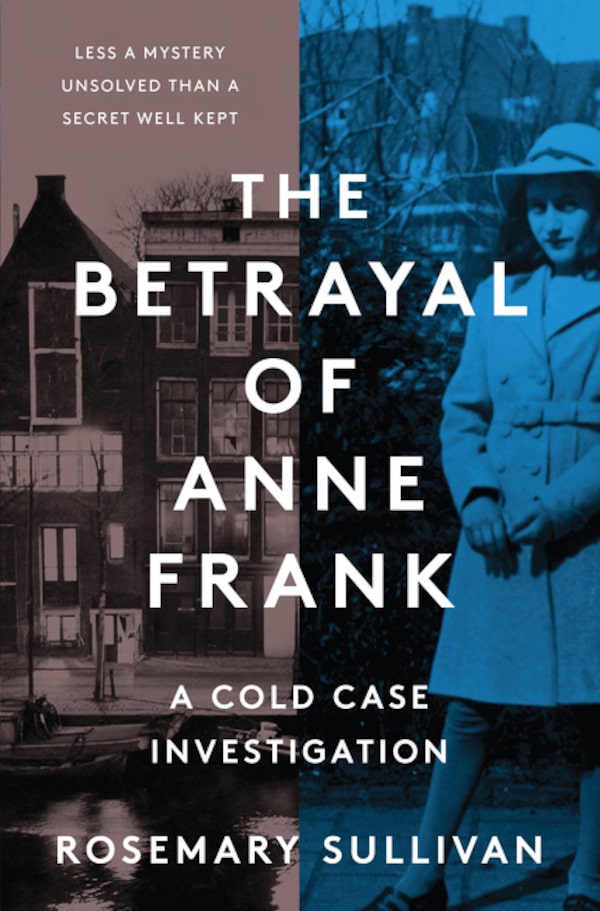

It is rather unusual that the study of the Holocaust and true crime intersect. But so it is in a new book by biographer Rosemary Sullivan – The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation – that attempts to solve one of the great mysteries of the Second World War: Who betrayed young Anne Frank, her family and the four other people who were hiding from the Nazis in a secret annex of an Amsterdam warehouse on Aug. 4, 1944?

The now-famous annex was located in a building at Prinsengracht 263, where German-born Otto Frank had once managed his business; a bookcase concealed their living area. The Nazi occupation of the Netherlands occurred in May of 1940. About a year later, Mr. Frank, complying with anti-Jewish regulations, was able to transfer his business to several non-Jewish members of his staff and designate Jan Gies, the husband of his secretary, Miep, the nominal director of the company.

Handout

In early July, 1942, Mr. Frank, his wife, Edith, and their two daughters, Margot and Anne, hid in the annex along with their friends, Hermann van Pels, his wife, Auguste, and their son, Peter. (They were joined later by Fritz Pfeffer, a dentist.) The Franks did so because Margot, then 16, had received official notification from Nazi administrators that she was to be sent to a labour camp in Germany. Refusal to comply with the order would have led to her arrest. And so they hid – for two years.

When the Gestapo arrived on that morning in August, 1944, and marched the Franks and the others out, 15-year-old Anne tried to take her notebooks, which were in her father’s briefcase. The notebooks were her precious diary, which she had been diligently writing to pass the long hours. Her journals contained reflections about her terrible situation, her family members and the others with them, as well as her deeply personal feelings about becoming a young woman. Despite the terrifying thought of capture, she was ever optimistic and planned to publish the diary in some form after the war.

As she was being led out, the SS officer in charge of the operation, Karl Silberbauer, grabbed the briefcase she was clutching, opened it and threw the notebooks onto the floor. He then filled the briefcase with any valuables he could find. In this moment of terror, there was a sad twist of fate: Had Anne been able to take the diary with her, it would certainly have been destroyed or lost; instead, after the Gestapo left, Miep Gies retrieved the diary and kept it, thinking she would return it to Anne after the war. However, only Mr. Frank survived – Mrs. Frank died from disease in early January, 1945, at Auschwitz, while Margot and Anne died from typhus five or six weeks later at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Upon Mr. Frank’s return, Mrs. Gies gave him the diary, which was soon edited and published – first in Dutch and then in English in 1952. It quickly became enormously popular. To date, it has been translated into at least 60 languages, and more than 20 million copies have been sold. It is taught in schools as a way of introducing the tragedy of the Holocaust to young students. The building with the annex was turned into a museum and (at least until COVID-19) attracted more than a million visitors a year. Walking through the bookcase door and up to the area where the Franks hid (which I have done on two visits) makes you realize how confining the two years they spent there must have been.

Thousands of Dutch Jews in hiding were discovered and taken into custody. Some were found through the efforts of Nazi “Jew-hunting units,” while others were turned in by neighbours or spies. The informants were mostly non-Jewish Dutch collaborators, but there were several Jewish ones too, such as Anna (Ans) van Dijk, who saved herself by agreeing to work for the Nazis. She was responsible for the arrest of at least 145 Jews – likely many more. Executed in 1948 for war crimes – the only Dutch woman to receive a death sentence – she was long regarded as a prime suspect in the disclosing of the Franks’ hiding place. So, too, was Willem van Maaren, who was hired in 1943 as the manager of the warehouse where the annex was located. He later proclaimed his innocence, and there is sufficient evidence to believe him.

Five years ago, a team of filmmakers, historians, archivists and criminologists led by film producer Thijs Bayens, financial executive Luc Gerrits and journalist Pieter van Twisk, along with Vince Pankoke, a retired FBI agent who assumed the role of lead investigator, set out to solve the mystery of the Franks’ betrayer. They used an artificial intelligence program to analyze thousands of documents and disparate facts to search for clues two official inquiries – not to mention countless other historians and writers – might have missed. Ms. Sullivan was recruited to chronicle their journey.

Ms. Sullivan does an admirable job providing the historical perspective and an account of an impressive research effort. Literally, no stone or document is left unturned. But no matter how much she and the members of the team want to believe and are convinced they have likely solved this mystery, they have certainly not. It is for this reason that several Dutch historians of the Holocaust have criticized the book and the team’s conclusions.

Near the end of the book, Ms. Sullivan identifies the most likely culprit – though not with “100-per-cent certainty,” Mr. Bayens recently told the Associated Press – as Arnold van den Bergh, a prominent Dutch Jewish notary who was a member of Amsterdam’s Nazi-created Jewish Council (Joodse Raad), which operated from early 1941 to late 1943.

The hypothesis is that in order to save himself and his family, Mr. Van den Bergh, who died in 1950, provided the Nazis with a list of addresses of Jewish hiding places, one of which was where the Franks were residing.

In the end, the case against him essentially comes down to a few pieces of evidence. Yet it is all speculative and circumstantial at best, with many questions unanswered. (As has been pointed out by several critics, throughout the book Ms. Sullivan uses such phrases as “likely,” “probably” and “although the team cannot be certain …”)

The main allegedly incriminating fact is an anonymous note sent to Mr. Frank in 1945, soon after he was liberated from Auschwitz, stating that the betrayer was “A. van den Bergh,” who had “a whole list of addresses he submitted [to the Nazi-controlled Central Office for Jewish Emigration].” Mr. Frank – who died in 1980 – briefly investigated Mr. Van den Bergh and much later shared information about the note with a few others, including a detective working on the 1963-64 official inquiry into the betrayal (who referenced it in his summary report) and likely Mrs. Gies (who died in 2010).

It is speculated that the existence of the note was not widely publicized because Mr. Frank presumably did not want to implicate a Jew in this crime, especially after Anne’s diary had become famous during the fifties and its authenticity was publicly questioned (and still is by Holocaust deniers). But Mr. Frank’s motives are merely guessed at. And far too much is ascribed to an off-the-cuff remark by Mrs. Gies in 1994, when she was 85. During a lecture she was giving at the University of Michigan, she was asked, “Who gave the Franks away?” and said the betrayer had died by 1960. This hardly incriminates Mr. Van den Bergh. Moreover, we do not know who sent the note to Mr. Frank nor why. Ms. Sullivan does concede that it may have been someone falsely accusing Mr. Van den Bergh.

The bigger issue is the claim that Mr. Van den Bergh and other members of the Jewish Council possessed a list (or lists) of Jews in hiding and possibly their locations, which he submitted to Nazi officials. “The team thought it highly probable” that Mr. Van den Bergh did have such a list, Ms. Sullivan writes. Whether this supposed list originated with someone on the council is unclear, and the anonymous note, if it is genuine, does not indicate that he obtained it from the council.

A letter found at the Amsterdam City Archives from Sybren Tulp, the pro-Nazi police commissioner, to SS commander Hanns Rauter, dated September, 1942, indicated that the council had provided names and addresses of mainly sick and elderly Jews who were to be deported – though there was no mention of them being in hiding. Also, according to Mr. Pankoke, the cold case team “found at least five [archival] references that indicate that the lists of addresses where Jews were in hiding existed, four of which are linked to the Jewish Council.” These references do not mention Mr. Van den Bergh (other than the anonymous note), and three of them are about individuals identified as spies and informants – Ms. Van Dijk is one of them – so they must be regarded with some caution. According to several historians, no actual list has ever been discovered. Mr. Pankoke’s response to this criticism is that this is not surprising, given that thousands of documents were destroyed in November, 1944, during allied bombing. He argues: “Just because we haven’t found the address lists, does not mean they didn’t exist.” Fair enough.

On the other hand, while Jewish Council members might well have had a list of names of Jews in hiding, how would they have amassed a list of secret locales where these Jews were concealed? Who would have told them this? And why on earth would they have done so?

Many Jews “distrusted the council because it openly co-operated with the German occupier in order to prevent retaliations [and] raids,” said historian Laurien Vastenhout of the Amsterdam-based NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies and author of the forthcoming book Between Community and Collaboration: “Jewish Councils” in Western Europe under Nazi Rule. “The Jewish [Council] chairmen were very clear about their policy of legality and urged people not to go in hiding. [They] did not support clandestine activities.”

One of the so-called “bombshell” facts (and one of the five references noted above) offered by Ms. Sullivan and the team proving that a list must have existed was based on testimony given in 1947 by Ernest Philip Henn, a German translator who worked for Luftgau-Kommando Holland (Air Force Command Holland). But it is pure hearsay. He claimed he had overheard a conversation between a military policeman and a court assessor that the Jewish Council “had a list of more than 500 addresses of Jews in hiding” and that the council had sent the military officer’s department the list.

And how had the council obtained this list to begin with? Mr. Henn stated that a Jewish woman had told him that “one way” was because Jews under guard by Nazis at the nearby Westerbork transit camp sent letters via the Jewish Council office in Amsterdam to their families in hiding – with the addresses of their hiding places noted. This is impossible to accept. Why would anyone in their right mind who feared for their family’s safety do this? In short, they would not have. If letters were sent from Westerbork, said Bart van der Boom, a lecturer at the Institute for History at Leiden University, they would have been “sent straight to the addresses and were not channelled through the Jewish Council, as the book claims.”

Additionally, it is not clear where Mr. Van den Bergh was in the summer of 1944, when the Franks were apprehended. He could have been in hiding, as some historians suggest.

Is it possible that the anonymous note Mr. Frank received in 1945 was correct – that it was Arnold van den Bergh who betrayed his family? And that he had a list of Jewish hiding places? Of course, that may have been the case. But as anyone who has ever done historical research knows, no matter how much effort you spend researching in archives and libraries and scouring old books, there are times you still cannot determine the truth. The recent indictment of Mr. Van den Bergh, based on the evidence presented, is one of those times.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.