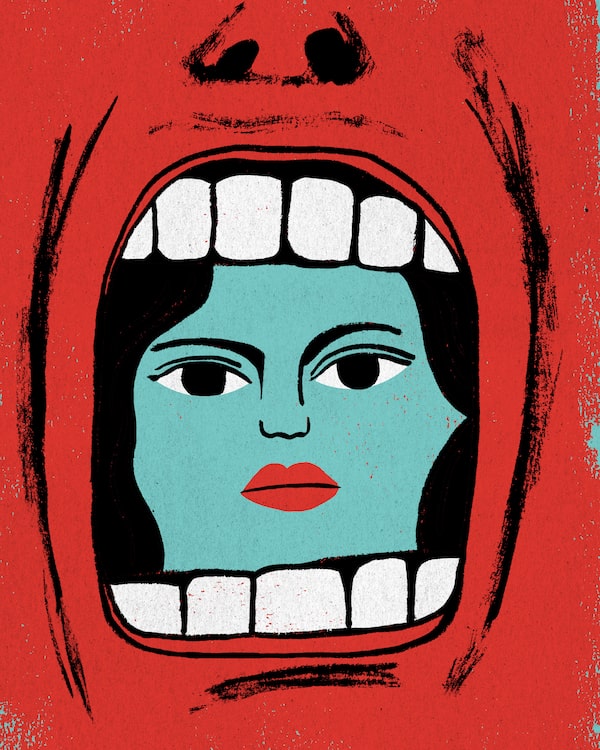

Illustration by Hanna Barczyk

Watching The Clinton Affair, A&E’s new documentary series, seeing who cries is instructive. Spoiler alert: It’s not Bill Clinton. Instead, it’s a woman who accused him of rape, Juanita Broaddrick, and one who accused him of harassment, Paula Jones. Even decades later, the emotional toll is clear as they remember, and cry.

Kathleen Willey, a former friend of Mr. Clinton’s who says he groped her when she came to ask him for a job, also becomes emotional in front of the camera when she talks about the consequences of speaking out: “We got hammered for it,” she said. “Ruined.”

Then, finally, there is Monica Lewinsky, who has emerged from the smoking rubble as a champion of empathy and victims’ rights. Ms. Lewinsky was involved in a consensual sexual relationship with the then-president, but it was also one with a great power imbalance at its heart. One of the participants got hung out to dry, and again, it wasn’t Bill Clinton. Getting to this place of balance has taken Ms. Lewinsky 20 years, decades that have been filled with more pain and therapists’ bills than most of us could imagine. “It’s a very long period of floundering,” she said, “and feeling unbelievably stuck in the old narrative of Monica Lewinsky that was created.”

Notice that she used the present tense to speak of something that happened 20 years before. The cost of being the victim of sexual harassment (or, in Ms. Lewinsky’s case, being solely blamed for a public scandal) never leaves; it lives in the mind and the body. This is what is so maddening about the current narratives around punishment and redemption in sexual-harassment cases. What’s going to happen to the poor men who’ve done wrong? Will they, as comedian Louis C.K. joked in a preliminary comeback stand-up set, forever be lamenting the US$35-million lost in an hour? Louis’s tragic loss of income, by the way, followed his serial pattern of masturbating in front of female colleagues.

When one of those colleagues, comedian Rebecca Corry, finally came forward and talked about his behaviour, she lost something worse: “Since speaking out, I’ve experienced vicious and swift backlash from women and men, in and out of the comedy community. I’ve received death threats, been berated, judged, ridiculed, dismissed, shamed, and attacked,” she wrote in Vulture. And yet, oddly, there has been no hand-wringing about how Ms. Corry might regain the spotlight.

I was thinking about this as the news broke that Ontario’s liquor stores would resumes sales of wine made by Norman Hardie, whose alleged sexual misconduct was outlined in a series of Globe and Mail stories this summer. Three women said Mr. Hardie had groped or kissed them against their will, and, according to the Globe story, “18 others described requests for sex by Mr. Hardie, and deliberately being exposed to pornography.”

Mr. Hardie issued a public apology on the company website, saying that “some of the allegations made against me are not true, but many are."

Restaurants and liquor-control outlets across the country suspended sales of Mr. Hardie’s wines. Only Ontario’s liquor stores has plans to resume sales, and to make matters worse, it has instructed its employees not to talk about the decision. One of the women who made the claims against Mr. Hardie told The Globe that the Ontario decision was “heartbreaking.” Heather Bruce, a former employee of Mr. Hardie’s, said: “It just makes you feel so small. It makes you feel like you don’t matter.”

This is the message again and again from women who’ve found the courage to come forward: You feel like you don’t matter. Instead, what we’ve decided to fixate on is the tremendous suffering of men who have behaved like predators (at best) or criminals (at worst). Is this because we’re hooked on redemption stories? Is it because we cannot fathom a world in which men’s material wealth and status might be stripped away as a consequence of their terrible actions? I have no idea. But I do know that we seldom give as much thought to what women have lost, through no fault of their own – physical and mental health, job security, professional advancement. There’s a hole in the world where their accomplishments should be, but we’ll never see it.

“I don’t know that anyone who comes forward and makes a charge of sexual misconduct, harassment, can have an easy time in a system that often assumes that they are not being truthful,” Anita Hill said this week when she came to Toronto to speak before the Canadian Women’s Foundation. Ms. Hill would know, having lived for the past 27 years with the consequences of coming forward with allegations of sexual harassment against Clarence Thomas, during his confirmation hearings for the U.S. Supreme Court.

Ms. Hill recently told The New York Times that she is in contact with Christine Blasey Ford, who came forward with her own allegations of sexual misconduct against Brett Kavanaugh, during Justice Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation. Justice Kavanaugh is now on the Supreme Court alongside Justice Thomas, and receives standing ovations at dinners; Dr. Ford still can’t return to her home because of death threats she’s received, and travels everywhere with a security detail. Yes, it’s a terrible price that men pay.

Ironically, some of the best reporting on the consequences of workplace harassment comes from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, where Ms. Hill and Justice Thomas worked together in the 1980s, and where she says the harassment occurred. According to a 2016 report from the EEOC, workplace sexual harassment is hugely underreported – 70 per cent of victims say they never make a formal complaint – and has profound consequences for those affected. As many as three-quarters of victims report some form of retaliation at their workplace. Many experience profound physical and mental-health consequences; some leave their jobs.

These consequences are all complex and dispiriting. They defy neat solutions, and don’t lend themselves to uplifting redemption arcs. If there’s no storybook ending, who wants to read?