Ontario Progressive Conservative Leader Doug Ford makes a jarring contrast with conservative predecessors like prime minister Stephen Harper and premier Mike Harris.Illustration by Antony Hare

John Ibbitson is writer-at-large at The Globe and Mail. He is also the author of Stephen Harper and Promised Land: Inside the Mike Harris Revolution.

We are at a gathering of the in-laws – three generations of children, parents and grandparents celebrating a birthday in a suburban small town on the fringe of Ottawa. Within the members of this family and their spouses or partners: a landscaper, a teacher, the owner of an auto-body shop, a police officer, a factory worker, a retired public servant, a caretaker, a film animator, a couple of students at community college, a retired bus driver, several homemakers.

As the children toddle and scream, I ask some grown-ups around the table how they plan to vote in the June 7 Ontario election.

Pete shakes his head. “I don’t know,” he says, “I just don’t know. That Kathleen Wynne, she’s gotta go. But Doug Ford? Doug Ford?” Everyone nods in perplexed agreement.

These people elect governments. Most of them live in suburbs. They commute by car. They value good schools, a decent hospital nearby, police who keep them safe, roads without potholes.

They also expect to keep most of the money they earn. They expect the governments that serve them to balance the books in good times and keep taxes within reason. They squirm at some of the things their children are being taught in sex-education classes. They are shocked by how much their hydro bills have shot up.

Although they often vote Liberal, in the 1990s such people supported Mike Harris’s provincial Conservatives. In the last decade, they voted for Stephen Harper’s federal Conservatives. But Doug Ford? Doug Ford?

Less than four weeks before the Ontario election, Mr. Ford’s Progressive Conservatives enjoy a strong lead in the polls, with the Liberals and NDP competing for second place.

Part of Mr. Ford’s appeal, says pollster Darrell Bricker, of Ipsos Public Affairs, is that “he is not Kathleen Wynne.” The Liberal Leader’s situation is comparable to Bob Rae’s in 1995, when his NDP government was defeated by Mike Harris’s conservative Common Sense Revolution.

But Mr. Ford is a very different kind of politician from Mike Harris or Stephen Harper. Belligerent and boastful, he promises not just change, but punishment. He promises to “audit Kathleen Wynne,” to fire the CEO and board of Hydro One, to scuttle efforts to combat global warming, to take the sex-ed curriculum away from the educators. He is, in a word, a populist, playing to rising resentment of middle-class voters toward elites.

“I govern through the people,” he declared last week. “I don’t govern through government.”

Voters might not care. In their determination to see the back of Ms. Wynne, they may be willing to vote for someone, anyone, who is not her. Thus far, the NDP’s Andrea Horwath has not convinced enough people that her party is preferable.

But if voters do choose Mr. Ford, they should do so knowing that they are voting for something very different from the past.

Mike Harris, Stephen Harper, Doug Ford. One of these is not like the others.

The Ontario Legislature at Queen's Park. For decades, moderate progressives dominated provincial politics, but the left and right became increasingly polarized in the 1990s.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

The Great Divide

Ontario voters have not been immune to populist politicians. In the 1930s, Premier Mitchell “call me Mitch” Hepburn sold off the lieutenant-governor’s mansion, auctioned off government limousines, expanded welfare, and introduced a minimum wage, while waging war against the union movement. His increasingly erratic behaviour cost him the premiership in 1942.

For the next four decades, Ontario voters – who make up almost four in 10 of the nation’s voters – hewed to a relentlessly moderate progressivism. Progressive Conservatives dominated provincial politics, just as Liberals dominated federally, occasionally replaced by Red Tory Progressive Conservatives who were virtually identical, ideologically, to their Liberal opponents.

“There was a general consensus in Ontario, Canada and the Western world about what politics meant,” says Jonathan Malloy, a political science professor at Carleton University who studies Ontario politics. “It meant: How do you manage prosperity?”

That prosperity came under threat in the 1970s and ‘80s, bringing political polarization to the province. The way forward is through smaller governments, lower taxes and trade. No, the way forward is through social investments, paid for by deficits and taxing the rich.

In the 1990s, Ontario voters switched first to the NDP, with its deficit-fuelled spending on social programs, and then to Mr. Harris’s Common Sense Revolution, with its cuts to taxes, spending and government services. In 2003, they rejected that approach in favour of Dalton McGuinty’s Liberals, who increased spending and launched a provincewide conversion to clean energy to fight climate change.

Former Ontario premiers Bob Rae, Mike Harris and Dalton McGuinty.The Canadian Press, The Globe and Mail

Federally, Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin’s pragmatic Liberals gave way to the country’s first genuinely conservative federal government. Mr. Harper favoured tax and spending cuts, fossil-fuel-based energy development, and a tough-on-crime approach to justice issues.

After a decade of Stephen Harper conservatism, Ontario voters opted federally for Justin Trudeau liberalism, which includes a return to budget deficits and a commitment to fighting climate change and to legalizing marijuana, but also support for free trade and oil pipelines.

Cheryl Collier teaches political science at the University of Windsor. She and Prof. Malloy co-edited the 2016 anthology The Politics of Ontario. Prof. Collier stresses that, while there are pendulum swings between progressive and conservative governments in the province, there is countervailing emphasis on “managerialism.”

“The greatest sin is to screw up the economy,” she observes. Voters punish governments of both the left and the right that are seen to mismanage that all-important issue, even if the government is not really at fault. “In politics, that’s the way it is.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne wave to the crowd at the federal Liberal national convention in Halifax on April 20, 2018.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press

We’ll know in a year and a half whether the Trudeau government’s progressive messaging but often conservative priorities still appeals to Ontario voters federally, but provincially, the centre cannot hold. Kathleen Wynne, Mr. McGuinty’s successor, has pursued a much more activist agenda on everything from clean energy to sex education. Voters in the 905 seem unimpressed.

The key to understanding Ontario politics lies in understanding the 905, the suburban belt surrounding Toronto, named after its area code. The 905 swings. Sometimes, it supports the liberal elites in Toronto – the 416. When that happens, governments emphasize environmental issues, public transportation and reducing income inequality. Keeping taxes down and budgets balanced – not so much.

When public finances fall into disrepair, the 905 rejects the 416 and allies with the 519 and 705 and 613 – the more rural and regional parts of Ontario, where the principal concern is about protecting jobs and building roads and balancing the books. The Conservatives come to power.

The Wynne government has been so unpopular for so long, that it seemed a slam-dunk that Patrick Brown would lead the Progressive Conservatives to victory. But Mr. Brown, who was trying to nudge the Conservatives toward the centre, was unpopular within his own party. When he was forced to step down over allegations of sexual misconduct, the party faithful opted for Mr. Ford, whom the Canadian writer Stephen Marche called “a tin-pot northern Trump” in a New York Times column.

“The deep-seated cultural and political alienation at the root of [President Donald] Trump and Brexit is in full force in Canada as well,” he declared. Is it?

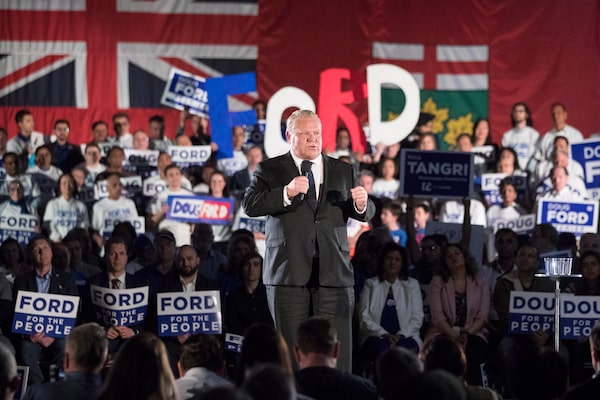

Doug Ford holds a rally in Toronto on May 8, 2018, to kick-start his Ontario provincial election campaign.Chris Young/The Canadian Press

The politics of anger

Mr. Ford, a businessman and former Toronto city councillor, has no experience as a provincial politician and little visible mastery of such complex issues as energy costs or the provincial health-care or education systems.

What he does have, at this point, is credibility among middle-class suburban voters who are fed up with what Mr. Bricker and I call Laurentian Elites – those downtown Toronto (and Ottawa and London and Kingston and so on) cognoscenti who heavily influence Liberal governments, and who Mr. Harris and Mr. Harper both ran, and governed, against. Mr. Ford is turning the 905 away from the 416 and toward the 519 and 705 and 613, just as they did.

The Progressive Conservative Leader appears to be popular with many immigrant voters – specifically, those who are doing well and living in suburban communities. People who decry Mr. Ford as a Canadian version of Donald Trump fail to reckon with the fact that Ford populism is not nativist. It embraces the more socially and economically conservative attitudes of people who came to Ontario from India, the Philippines, China and other developing nations.

Prof. Malloy, while acknowledging Mr. Ford’s “very unguarded, shoot-from-the-hip style, to say the least,” detects in him “a reasonably coherent view of the world … and I don’t think it’s that different from Mike Harris or Stephen Harper.” So, lower taxes, smaller government, fewer regulations, continuing commitments to public health-care and education, but little interest in environmental issues.

But there remains a fundamental contradiction between Harris and Harper conservatism and Ford conservatism. Both Mr. Harris and Mr. Harper were aware that populist anger at elites drove part of their voting base. But while they channelled that anger, they never succumbed to it. Both espoused a consistent, usually coherent, conservative message that kept the mob at bay.

But Doug Ford isn’t a conventional conservative. In his populist zeal, he stokes public anger, just as brother Rob did as mayor of Toronto with his vow to “end the gravy train.”

Doug Ford and his brother, former mayor Rob Ford, at Toronto City Hall in 2013.Aaron Harris/Reuters

Rob Ford, who died of cancer in 2016, achieved little, apart from partly privatizing garbage collection, because he alienated other council members, and his mayoralty was brought down by his substance-abuse problems. But he was memorable for going on about government waste, although he found little he could cut. He celebrated the car and disparaged the bicycle, while opposing ambitious plans for public transit. He tried to get a casino built. As councillor, Doug was with his brother all the way, including the belligerent, us-against-the-elites rhetoric.

More than polarization of the left or right, Prof. Collier believes, politics sometimes polarizes between populists and elitists, especially in Toronto – witness the suburban success, not only of Rob Ford, but of Mel Lastman, the first mayor of the amalgamated city, versus downtown-approved David Miller and John Tory, the current mayor.

But is Doug Ford ahead in the polls because of his populism, or despite it? Are Ontario voters looking for a diluted strain of Trumpism, or are they prepared, reluctantly, to tolerate it as a something/anything alternative to Ms. Wynne?

Mr. Bricker maintains that the bond between populist voters and ordinary conservative voters is their anger at the Liberals and their fellow travellers who, many voters believe, have mismanaged the province, worrying more about climate change than commuting times.

That anger is expressed even more forcefully south of the border, where a large cohort of voters believe that established interests and institutions no longer represent them and their concerns.

“You’ve got an energy that needs to be directed toward something, and clearly the establishment parties of the right and the left in the old order weren’t satiating this demand for a new direction,” says James Moore, the former cabinet minister in Stephen Harper’s governments who today is chancellor of the University of Northern British Columbia.

“You have to have the relief valve of politics to absorb that energy. Otherwise, it could go into some pretty dark places.”

The challenge for the conservative movement, in Ontario and Canada, is to define a coherent conservatism that channels populist anger at institutions and elites, without going to that dark place.

In terms of policy choices, to the extent we know them, Doug Ford appears to be a solidly blue conservative who, in his drive for smaller government, infuriates progressive elites, and does so with glee. That makes him the third in a trilogy of politicians that includes Mr. Harris and Mr. Harper.

Oct. 17, 2015: Doug Ford and his brother Rob, bottom left, listen to then Conservative leader Stephen Harper during a campaign rally in Toronto.JONATHAN HAYWARD/The Canadian Press

It is also perfectly reasonable to have voted for Mike Harris and for Stephen Harper, but to be uncertain about whether to vote for Doug Ford. Will he bring competent conservative government to Canada’s largest province? Or will he gin up anger and divisions? Will he surround himself with, and listen to, people who know more about governing than he does? Or will he cater to the cranks?

His performance as city councillor suggests that he would make a combative and divisive premier. However, his decision to protect the Liberal-created Greenbelt surrounding Toronto, reversing a previous pledge to developers, and his expulsion of former leadership candidate Tanya Granic Allen, who was running in Mississauga Centre, because of her strongly socially conservative views, means he could be open to moderating influences.

At Monday’s leaders’ debate, he was both combative – accusing Kathleen Wynne of making “backroom deals“ and of Liberals “gouging the taxpayer and paying off their cronies.“ And yet he displays, at his best, a disarming simplicity. “You know me – I’m for the little guy.“

For voters – and I suspect there are many across the province – who were looking forward to a conservative rebalancing after the McGuinty and Wynne years, but who fear the importation of a Trump-like circus into Ontario politics, the choice is painful.

You support the Conservatives. But Doug Ford? Doug Ford? And if not Doug Ford, then who? Is Andrea Horwath really a non-starter as an alternative to Kathleen Wynne? Really, truly, did Kathleen Wynne do that bad a job?

At that dinner table, no one seemed certain how they would vote. But they all agreed they faced an interesting choice.

Liberal Premier Kathleen Wynne, centre, looks on as Progressive Conservative Leader Doug Ford, left, and NDP Leader Andrea Horwath shake hands at the Ontario leaders debate in Toronto on May 7, 2018.Frank Gunn/The Canadian Press

John Ibbitson

John Ibbitson