The World Cup has been an occasion for much crying, such as Brazil's Neymar, middle, who wept after scoring a goal against Costa Rica on June 22. But there are plenty of other situations that can bring men to tears. Far-left column: A Mountie at a memorial for four slain comrades in Edmonton; a man at a day of remembrance for China's Nanjing massacre. Second column: NHL veteran Mark Messier at a ceremony to retire his number from the New York Rangers; a firefighter at a Winnipeg memorial in 2007. Far-right column: A Canadian soldier mourns his friend, killed by a roadside bomb in Afghanistan, in 2006; a man watches Michael Jackson's memorial in Toronto in 2009.AFP/Getty Images, Associated Press, Reuters, The Canadian Press and The Globe and Mail

Rachel Giese is the author of Boys: What It Means to Become a Man.

Neymar on his knees at the final whistle, face buried in his hands, sobbing in joy and relief after scoring the second of Brazil’s two extra-time goals against Costa Rica’s stubborn, scrappy underdogs. This dramatic reaction by the star forward at a group-stage match in the World Cup became an instant flashpoint. On Twitter, Neymar was knocked by fans who thought he was over-reacting (one called him “the most shameless player in football”). ESPN’s football panel devoted an entire segment to debating whether his weeping was disingenuous. Media at home in Brazil slammed Neymar’s tears (as well as his theatrical dives): “A team needs to demonstrate mental strength, not fragility,” ran a story in O Globo, one of the country’s biggest newspapers. “Genuine or not, Neymar’s crying is worrying.”

It’s not that crying is unwelcome at the World Cup. The tournament is generally awash in tears – four years of pent-up anticipation and global rivalry will do that. Panama’s commentators welled up when they heard their national anthem being played for the first time at a World Cup, legendary footballer Diego Maradona wept openly in the stands watching Argentina narrowly struggle through its early games and, following Mexico’s victory over Germany, striker Javier Hernandez bragged that among his teammates, “I was the one who cried the most.”

It’s not even that crying is unwelcome in the broader sports world – athletics are one of the rare venues where the usual prohibitions against male tears are relaxed. In fact, emotional reactions by male athletes are not only permitted, but often valorized. It’s a signal that a player has heart, that he takes his work seriously, that he’s left it all on the field and then some. Roger Federer broke down after his loss to Rafael Nadal at the Australian Open final in 2009. When P.K. Subban returned to Montreal to play the Canadiens for the first time after being traded to the Nashville Predators, he teared up during a tribute to his contributions to the city. Search “NFL players crying” and you’ll come up with hundreds of videos of burly men sobbing, over defeats as well as victories.

Neymar’s problem was that his tears weren’t the acceptable sort of sports tears. He cried “like a baby,” not a jock. And that distinction proves to be critical. In a 2015 paper titled There’s No Crying in Baseball, or Is There?, Pennsylvania State University psychologists Heather J. MacArthur and Stephanie A. Shields argue that in sports – contrary to the usual macho stereotypes about being tough and stoic – crying is prevalent but comes with a caveat. The expression of “ideal” male emotion, they write, does not involve “the complete rejection of emotion, but is instead constructed as doing emotion in a way that can be defended as ‘not feminine.’” Even tears are gendered, it turns out, and there is a masculine and feminine way to cry.

Crying as an expression of vulnerability or as a response to being overcome is viewed as feminine – or, at least, insufficiently manly. For men, brimming eyes and single tear streaming manfully down a cheek is acceptable. Bawling is not. Mr. Hernandez’s tears are heroic, Neymar’s histrionic. There are long-standing complaints about Neymar’s self-indulgence: When he teared up at a press conference last year, Craig Burley, a football commentator and former Chelsea player, called him a “cry-baby” and the “most petulant guy” in world soccer. But the anxiety over Neymar’s abundance of emotion appears to be as much a concern about his masculine bona fides as it is about his capacity as an athlete. Neymar is, after all, an exceptionally talented forward from an exceptional football nation. His theatrics grate on his critics, but some of their discomfort stems from what looks like his flouting of male norms.

And Neymar isn’t alone in being a brilliant athlete condemned for looking soft. After he cried during his Basketball Hall of Fame induction in 2009, Michael Jordan’s tear-streaked face became a mocking meme, Mr. Jordan’s genuine emotion over the honour was deployed as a joke.

These narrow parameters for athletes’ emotional expression reflect an overarching anxiety over signs of weakness in men – the imperative that “boys don’t cry” being one of the most ubiquitous ways of policing their behaviour from a very early age. Being tough, rational and remaining calm under pressure are prevailing male norms. Crying is associated with a kind of vulnerability and openness that we’re still uncomfortable with boys and men expressing. Among guys, except in rare circumstances, tears remain largely taboo.

Sports is one of the areas where taboos against male crying can break down. Clockwise from top left: Oakland A's pitcher Dave Stewart in 1995; German middleweight boxer Peter Mueller in 1956; Wayne Gretzky, then announcing his trade to the L.A. Kings, in 1988; Jiri Fischer of the Detroit Red Wings in 2005; and New York Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig in 1939.Reuters, Associated Press

Physiologically, the function of tears is to keep our eyes lubricated and clean. Like other animals with tear ducts, we well up reflexively when a bit of debris gets in our eyes. But while non-human creatures relay their distress and pain by wailing and howling, it’s only us who cry tears in response to heartache, grief, stress and joy. Michael Trimble, a British neurologist and author of the 2012 book Why Humans Like to Cry, has said that emotional crying, more than any other trait, is what distinguishes us as human beings – not even our closest primate kin cry this way.

Why we do so isn’t entirely understood. Dr. Trimble and others have theorized that we developed the capacity for emotional crying as a way to communicate our feelings to one another and establish empathy and social bonds. Tears are signal that someone needs our comfort and attention. This may be why the sight of someone else weeping can trigger tears in us – we can, in fact, feel their pain.

Yet, even though the capacity to cry is human, over time and across cultures, there has been wavering acceptance of emotional crying, especially for men. Ancient heroic tales included accounts of noble grief, such as a warrior mourning fallen comrades, or an emperor weeping at the prospect of military defeat. At the same time, crying was associated with an unmanly wimpiness, or worse, as a form of female treachery and manipulation. Dr. Trimble cites Homer describing Odysseus as weeping “like a woman” when he hears songs about the Trojan wars, and hiding his tear-streaked face in shame. Centuries later, in The Taming of the Shrew, William Shakespeare writes: “And if the boy not have a woman’s gift/To rain a shower of commanded tears, An onion will do well for such a shift.”

Today, social and cultural differences remain. Cross-national studies of adult crying have found that, while everyone cries, why and when we do so is, in part, shaped by social norms. People in more affluent, democratic, extroverted and individualistic countries report that they cry more often than those in poorer, less equitable and more communal ones. The people in the first group, in richer, freer countries, arguably have less to cry about – but they live in cultures that are more permissive and encouraging of emotional expression. Other research has found that people in the West cry more now than they did 40 years ago. Since 9/11, American culture, in particular, has become more accepting of adult emotional crying.

Men still cry less than women, though. One frequently cited statistic is that men report that they cry on average once a month, while women say they do 2.7 times each month. There is some evidence that this disparity may be hormonal: Testosterone is thought to inhibit the production of tears. But Ad Vingerhoets, a Dutch psychologist and author of Why Only Humans Weep: Unravelling the Mysteries of Tears, has said that shedding tears is not just “a reflex-like symptom. We are more in control of our crying than we are aware of.” In other words, we can choose, to a degree, whether or not to display our tears. And men and boys tend to stifle them.

We don’t start out this way. At the beginning of our life, there isn’t any distinct sex difference when it comes to crying – all babies and toddlers do it. But as children get older, there is an observed difference in how their crying is viewed. Tears as a sign of hurt, sorrow, vulnerability are accepted, even expected, in girls. Beginning as early as pre-school, parents tend to encourage expressions of sadness in their daughters, but not their sons. Around the age of 12, boys receive more parental disapproval when they cry than girls do. Within peer groups and at school, boys who can’t hold back their tears are at a higher risk for being teased. Boys also tend to express more shame and embarrassment about crying than girls do.

Politicians of all countries and eras have had their share of crying moments. Clockwise from top left: Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2012; U.S. president Bill Clinton and his wife, Hillary, in 1997; Alberta premier Ralph Klein in 2006; U.S. House Speaker John Boehner in 2011; Brazilian ex-president Luiz Inacio Lula Da Silva in 2016; and Quebec premier Lucien Bouchard in 2001.AFP/Getty Images, Associated Press, The Canadian Press

Hypermacho, unquestionably manly environments such as sports and the military have long provided a cover for tender male emotions. They’re forums where “real men” can enjoy a good cry – provided, as Pennsylvania State’s Ms. MacArthur and Ms. Shields explain, that they appear to be in control of those feeling. What men can cry about is also important. Manfully tearing up over your team’s hard-fought victory is acceptable; gasping sobs over your wounded romantic feelings less so. It’s no accident that women’s tear-jerker movies tend to focus on thwarted love, while the film genre known as “the male weepie” consists of sports flicks and buddy movies such as Field of Dreams, Brian’s Song, The Shawshank Redemption and Creed.

This limited permission for male emotion is often described as “passionate restraint,” or the capacity to be moved by events and circumstances without letting your emotions get the better of you. In this equation, women are typically seen as being easily overcome by their feelings (they are “crazy” and irrational) whereas men are perceived to be reasonable and in charge.

This is sexist double-standard is, in part, why jokes about “drinking male tears” began to circulate among feminists in response to the angry backlash of online misogynists – men who complained and sulked about every perceived slight or encroachment into their territory, such as an all-female Ghostbusters reboot, or a critique of sexist rape jokes. Hoisting a coffee mug inscribed with “Male Tears” is a way for women to jokingly critique a subset of guys who claim to hate cry-babies and delicate snowflakes, while at the same time crying and moaning a lot themselves – now who’s the emotional one?

And sexism surrounding crying is also why women are often said to be unfit to be political leaders (what if she has PMS and nukes Russia?) and why restrained displays of emotions by male political leaders are, by contrast, often seen as a kind of strength. Even the occasional tear is permitted when it seems appropriate.

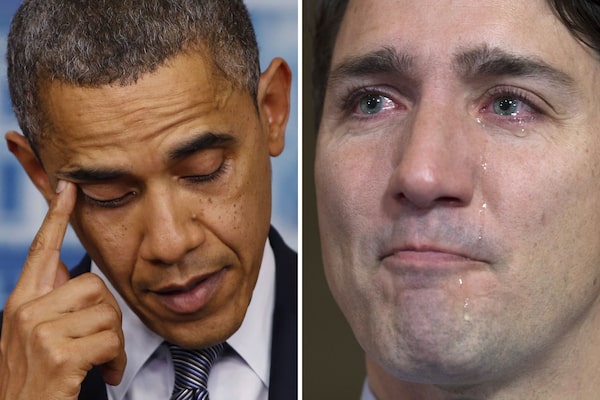

Former U.S. president Barack Obama famously welled up discussing the 2012 mass shooting of children at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. Many viewed his response favourably, a sign of his humanity and commitment to reasonable gun control measures. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has cried publicly, and his emotional IQ is seen as strength by his supporters. He teared up discussing Gord Downie’s death with reporters and during his apologies to LGBTQ2 citizens who were persecuted by the government.

Still, these displays are protected by the fact that these leaders have established masculine credentials: both are heterosexual and conventionally handsome, and they like guy sports (basketball and boxing). The leeway they’re offered to cry wouldn’t be afforded to a female politician, or to a male one who was gay, or seemed unmasculine. Consider that in a study in which subjects were shown a range of images of people crying, men with a slight moistness in their eyes (a sign of strong emotion, under control) were viewed the most positively of all. They were crying like a man.

Left: U.S. president Barack Obama wipes away a tear as he speaks about the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., on Dec. 14, 2012. Right: Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau cries as he speaks about the late Tragically Hip singer Gord Downie in Ottawa on Oct. 18, 2017.Reuters, The Canadian Press

The beliefs that “boys don’t cry” and that “crying is for girls” are oppressive for men and women both. As long as emotion is equated with both femaleness and weakness, women and girls will be perceived as irrational and incapable, while men and boys will continue to repress their feelings of sadness and vulnerability.

But maybe we’re seeing the beginnings of change: One of the most popular shows on TV is the ultraweepie This is Us, a rare example of a story in which men are more openly emotional and teary than women. It’s refreshing to see male characters embrace the expression of not just happy cries and sad ones, but also emotional distress, anxiety and fear.

Perhaps examples such as this, and the teary floodgates of the World Cup could be a model moving forward – a reminder that hiding or restraining hurt, joy and weakness isn’t a requirement for manhood. Champions can bawl, too.

Costa Rican defender Bryan Oviedo consoles Brazilian forward Neymar at the end of their June 22 match.GIUSEPPE CACACE/The Canadian Press