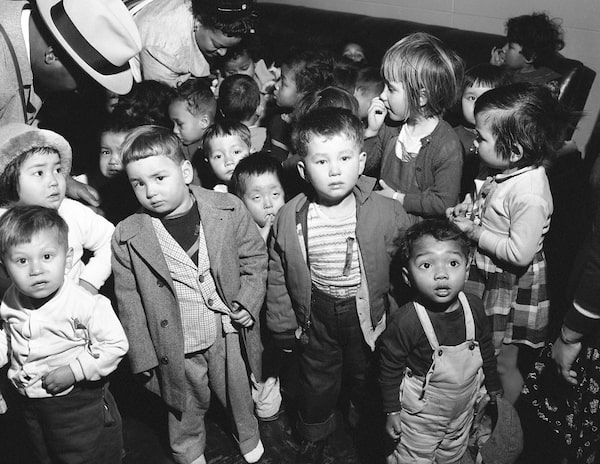

This photo shows some of the 89 Korean orphans who arrived on a chartered plane in San Francisco on Dec. 17, 1956.Ernest K. Bennett/The Associated Press

Jenny Heijun Wills is the author of Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related, which was recently shortlisted for the Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Nonfiction.

Phillip Clay was an adoptee, like me. We were part of the same wave of transnational adoption from South Korea, but whereas I arrived in Southern Ontario in 1982, he landed in Philadelphia the following year. We both hailed from Seoul, an electric capital city that today is one of the most densely populated places in the world. We both returned, under different circumstances, to that land that now seems so foreign, years after being away. He was 8 when he met his white adoptive parents. I wasn’t yet a year old. I don’t have a birth certificate. I suspect he didn’t, either. I’m on no one’s family registry. Again, I assume the same was true of him. But my parents secured citizenship for me in my adoptive land. Phillip’s parents did not.

In 2012, Phillip was deported from the United States to our birth country. He had no connections, no cultural context, no language. Perhaps parts of his upbringing had been similar to mine, both of us in the tail end of an assimilation-centred era of transnational adoption. I wonder if he tried to distance himself from anything Korean when he was small, hoping, as I did, that his difference from the other people would dissolve if he didn’t draw attention to it. Maybe he, too, in adulthood, felt the simultaneous longing for Korea and absolute terror of being in a place that means so much but feels so unfamiliar. Of course, whenever I’m in South Korea, that fear is softened by the knowledge that I can always return to the place I know. To the place I was raised. But that comfort, too, is discomforting.

There is a community of returned adoptees living in Seoul, but their situations there, like mine, are/were different from those of Phillip Clay. He could not leave that place but he also could not stay. He could not leave because he had nowhere to go. He could not stay because he had nowhere to be. And so, in 2017, Phillip Clay rode an elevator to the 14th floor of a building in a small but impressive city called Ilsan, just southwest of Seoul, and flew out into the night. To the hard world below.

Korean adoptees around the world grieved his suicide, but also his troubled life – the disproportionate injustice he faced and the pain with which he lived. Anger also streamed forth as adoptees tried to make sense of a transnational adoption system that results in further adoptee dislocation. Adoptee statelessness. It is the same system that Adoptee Rights Campaign members try to hold accountable as they fight for what they estimate to be the 35,000 adoptees from around the world whose American adoptive parents failed to secure U.S. citizenship for them. The same system that Adam Crapser, another Korean adoptee who was deported from the U.S. two years ago, describes in his 2019 lawsuit against the South Korean government and his adoption agency in Seoul. The same system that reaches into other places, too: Adoptees from Vietnam, Thailand and Brazil have also faced deportation for similar reasons – only learning in adulthood that they, once 18, are undocumented. That they do not belong in their adoptive land. That, in fact, they belong nowhere.

Transnational adoption from South Korea began in 1953, the same year the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed. It began in large part because of the growing number of both war orphans and the children of American soldiers, who were ostracized by a society that valued patrilineage and ethnic “purity,” among other things. Since that time, an estimated 250,000 young people have been sent from South Korea to foreign lands on one-way “orphan” visas, raised in places such as Canada, the United States, Western Europe, Scandinavian countries and Australia.

South Koreans expressed shame over their transnational adoption program when the world turned its attention to the country during the 1988 Seoul Olympics, but the industry persisted. The program continued despite rapid economic growth in South Korea and continues today, even though the country is experiencing a population crisis due to falling birthrates.

Unsurprisingly, the U.S. became the main destination for Korean adoptees in the years following the Korean War and still is today. The peak of Korean international adoption was in the 1980s, and the practice has been in decline for the past few years.

Although some steps have been taken to protect transnational adoptees from deportation, more must be done. Importantly, though, this work must not simply seek to secure exemptions for adoptees without proper documentation; it should focus on reforming xenophobic and cruel immigration policies more broadly.

The Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2000 granted U.S. citizenship to adopted people who were born in another country after 1983 (in other words, who were under 18 when the act came into effect in 2001) but excluded the thousands of adult transnational adoptees who had immigrated without their consent and had been raised as American children. And while deportation is the greatest threat, stateless transnational adoptees can face obstacles when applying for passports to leave their adoptive lands, registering for social and/or student assistance or obtaining a driver’s licence.

Most recently, senators from Missouri, Maine, Hawaii and Minnesota – the state with one of the highest rates of transnational adoptions – introduced an updated Adoptee Citizenship Act (2019). The bipartisan bill would remedy the issue by granting retroactive citizenship to all transnational adopted children of American parents.

In Canada, citizenship for transnational adoptees falls under the purview of the Citizenship Act. An adoptee or an adoptive parent can apply for a grant of citizenship, with the caveat that the first-generation limit to citizenship excludes adoptees whose adoptive parents were themselves born outside Canada. The first-generation limit also precludes transnational adoptees from passing on their citizenship to any children born outside Canada, biological or adoptive. In other words, transnational adoptees can be granted direct citizenship only if their parents were born in Canada, but their own children will not inherit citizenship if they are born in another country. To circumvent these restrictions, some Canadian parents opt instead to apply for permanent residency for their transnationally adopted children, with the understanding that, if the adopted person later applies for citizenship, they may be exempt from the first-generation limit.

The recent crisis of transnational adoption and citizenship is even more insidious than all this. In a cruel revision of the pattern of children being sent out of their birth countries and cultures, we are witnessing more and more parents being deported, deemed “illegitimate” or “illegal” (i.e. undocumented) immigrants, with young people winding up in the care of the country that managed to transform them into adoptable orphans. Agencies such as Bethany Christian Services, despite protesting the separation of children and their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border, have already begun placing these children in new homes and families. We know, to borrow from my colleague and fellow Korean adoptee, Dr. Kimberly McKee, that the U.S. and many of its private adoption agencies are working together to “create potential adoptees” through the detention and deportation of their parents.

Regardless of one’s opinion on these tactics, one thing is certain: We can no longer naively accept the comfortable narrative that the parents of adopted children always have agency or choice or that they would want their children to be raised by others in another country. We must admit the continuing, primal pain of separation and the terrifying power the state holds over how present and future kinship might be experienced.

This opens a host of questions about reunion, citizenship and possibility. When I reunited with my Korean family, I had a Canadian passport, the right to travel to my birth country and, when my time there was over, the right to leave. I can return to visit my Korean relatives and, should I so choose, stay for months at a time. My Korean sister lives in Canada now. My Korean parents visited to attend my wedding in 2010.

Will young people today, adopted in the U.S. and with transnational parents, be eligible to obtain U.S. passports? What, if it is even possible, would their reunions and returns (temporary or otherwise) look like? Will they one day also be deported if not protected by the Adoption Citizenship Act? Can they travel to their countries of origin and/or the countries of their ancestors? If they do, can they ever again leave? Presumably, their parents will be disqualified from returning to see them in the United States. In other words, has transnational adoption finally devolved to a point where reunion, what already goes against the odds, what already seems (and usually is) impossible, really is? While it is not the case with all, there are some adoptive families who opt to participate in transnational adoption because of the perception that the break with first families is final, that there is no possibility of reunion. Some of us have been fortunate enough to prove otherwise. That we always find a way home.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.