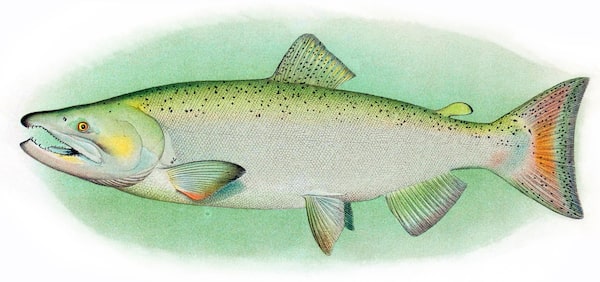

An adult male chinook salmon, from The Fishes of Alaska, 1907. The Yukon River, the world's longest salmon run, is where chinook salmon travel to every year to reach the spawning grounds where they were born, and will then die.PUBLIC DOMAIN

Adam Weymouth is the author of Kings of the Yukon: A River Journey in Search of the Chinook.

Teslin, Yukon Territory, has a population of roughly 450, the majority Tlingit First Nation. The Alaska Highway crosses Teslin Lake here on a long bridge of steel girders. The road came through in 1942 – part of the war effort, in case the Japanese turned up via Alaska – and Teslin transformed, in a few short weeks, from a remote bush community into an overnight drive to Vancouver. Elders still remember bulldozers cresting the horizon and forging a path toward their village.

Teslin sits on another highway, too. The lake fills from Nisutlin Bay, and flows out by way of the Teslin River, which in its turn feeds into the Yukon River at a spot called Hootalinqua. From there, it winds west out of Canada, bisects Alaska and comes, at last, to the Bering Sea.

Each spring, the chinook salmon, which have spent the majority of their adult life far out in the Pacific, enter the Yukon Delta and commence their journey upriver, aiming for the spawning grounds of their birth. Many will peel off into tributaries across Alaska, but plenty will cross the Canadian border, and some of those fish will make it as far as Teslin.

The Yukon River is the longest salmon run in the world: Those fish that travel farthest swim 3,200 kilometres against the current. Navigating by their sense of smell, an imprint of the mineral makeup of the waters of their youth, they return to the exact same pools where they were hatched, to spawn and then to die. It is said that pilgrimages began with nomads returning to the graves of their ancestors: Such is the salmon’s return.

For as long as anyone could remember, the Tlingit of Teslin would make fish camps along the lake each summer as the salmon neared their village, setting nets or drifting them from boats, harvesting this annual bounty. The people here, along with the others who line the river’s banks from Teslin to the sea, could stock enough fish in their caches to make it through the coming winter. Unlike moose hunting or muskrat trapping, this annual influx of protein was reliable, and arrived on cue at fishing spots that had been used for generations.

Fish camp is often remembered as a happy time, full of abundance. A time for swapping stories, for catching up with friends, for teaching the youngsters how to fish and how to respect the water. Fish were roasted on open fires; fish were cut and dried and smoked and packed away for the coming winter of 40 below.

But that was then. Twenty years ago, the First Nations of Teslin decided to stop fishing for chinook. Their elders had been telling them for years that something was happening to their fish, and it had reached a point where no one could ignore that not just their overall numbers, but also their individual size, were dramatically in decline.

One of the chinook’s nicknames had once been the June hog; 80-pounders were not uncommon. (In 1949, near Petersburg, Alaska, a 126‐pounder was caught in a fish trap, the upper limit of a featherweight boxer.) Now, a good fish was 20 pounds. And, because smaller fish lay fewer eggs, every summer, there were fewer salmon returning.

In Teslin, the people had tried restricting their fishing to five days of the week, then to three days, then two. Nothing seemed to make a difference, and 20 years ago, they took a collective decision to lay off it altogether. It was intended only as a temporary move, until the runs picked up. But the runs never did pick up, and Teslin has yet to return to subsistence fishing.

Situated at the Yukon’s headwaters, those in Teslin were the first to have seen the changes that the chinook had undergone. But every community downriver is now suffering with the declines. Before 1997, an average 300,000 chinook entered the Yukon River every year. In 2013, just 37,000 fish came back. In 2014, and again in 2015, fishing for chinook was banned entirely on both sides of the border, an unprecedented move.

Since then, some limited fishing has been permitted. But the Tlingit of Teslin, and also the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in of Dawson City, have elected not to catch chinook, as have many fishermen in Alaska. In Dawson, the youngsters are now taught how to prepare fish with salmon from the freezer; it can be hard to generate the same excitement. In Teslin, they fly their fish in from Atlin, B.C., another Tlingit community many kilometres to the south. There are those in their late teens, those who have never caught a fish, who associate the drone of a bush plane from beyond Mount Bryde with the start of the salmon run. Flying fish, they call it now.

Preparing salmon at Rampart village along the Yukon River. In his travels along the Yukon River, Adam Weymouth fished with the people whose livelihoods depend on the salmon runs.Ulli Mattsson

Salmon strips drying on the Yukon's banks. Fishermen who once saw 80-pound chinook salmon can now find only 20-pound fish, which produce fewer eggs – meaning slimmer prospects of bigger salmon in the future.Ulli Mattsson

It is not only the people on the river who have developed a life intimately bound up with the chinook. As the salmon flow into the continent, they bring with them the nutrients and minerals they have amassed from a life at sea. There is perhaps no image more iconic of the northern wild than a bear haunch‐deep in the turbulence, fielding leaping salmon like a goalkeeper.

A grizzly can get through 40 salmon in eight hours. Where the salmon are plentiful, bear numbers can be 80 times higher than elsewhere, and the quantity of salmon they get through before hibernation directly influences the number of cubs they will give birth to the next spring. There are more than 50 mammals – otters, wolverines, lynx – that draw sustenance from the chinook.

As the salmon carcasses break down into the soil, the carbon and nitrogen and phosphorus and fat that they carry in their bodies from the oceans are spread throughout the ecosystem. Along some streams, the concentration of nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil can exceed that of commercially produced fertilizer. Up to 70 per cent of the nitrogen in these forests had its origin in the sea. Imagine, if you like, the salmon swimming up the capillaries of the spruce and birch; it is not so far from the truth. If you know the land well, you can gauge the state of the salmon run by the fecundity of the forest. Up the Porcupine River, where the chinook no longer come, the forests are dying.

What is driving the decline of the chinook? There are as many theories as there are fishermen on the river. But what is certain is that the salmon are now smaller, a result of a long-term lack of regulation by the government on net size (the Yukon may have been the last large-mesh commercial salmon fishery in the world) and a deliberate targeting of the biggest specimens by fishermen.

The largest fish would have been the strongest fish with the farthest to travel, those bound for Canada. The upshot has been a skewing of the genetics in favour of smaller fish. Rather than the 20,000 eggs that the 80-pounders used to lay, smaller fish lay closer to 5,000, and rather than five fish returning for every spawning adult, it is closer to one to one.

That does not leave much resiliency in the system. And the other knocks the chinook are now taking – overfishing in the oceans, warming waters that are exacerbating the spread of diseases and algal blooms – are consequently being felt much harder.

Fertilizing salmon eggs at a hatchery in Whitehorse. An 80-pound salmon would lay about 20,000 eggs, while smaller fish lay closer to 5,000.Ulli Mattsson

I first became aware of the decline of the chinook when I travelled in Alaska in 2013. In Bethel, a town of 6,000 people far out on the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta, I reported on the trial of 23 Yu’pik fishermen accused of catching chinook at a time when the Alaska Department of Fish and Game had placed a ban on the catching of the salmon. Yet the Yup’ik had chosen to go out and fish – had even news-released their intentions to do so. They defended the taking of salmon to be as much a part of their culture, their spiritual practice, as it was for the filling of their larders. In the courtroom, there were tears and impassioned speeches, and I began to see how deeply entwined were the lives of the people and the fish.

The farther that I travelled in Alaska, the further I uncovered this connection, whether it was First Nations fishing at their ancestral spots, or urban families jumping in the car on the Fourth of July weekend to go catch some salmon for the freezer. The people seemed as wedded to the rhythms of the fish as the fish were to those of the landscape.

Since that initial trip, I have returned to the North twice more. For the past two summers, I have canoed the length of the Yukon River, the same distance as the salmon that travel farthest (albeit my journey was downriver rather than up) to try to better understand how those who rely on the chinook’s annual arrival are coping with the decline. I travelled at the same time as the salmon run, and I spoke with people, fished with them, shared their food and heard their stories.

I came to see that to ask people questions about the chinook was to probe deeper into their lives. It was to ask them how they thought about the food they ate, about what they hoped for their children’s futures. About what it meant to be Indigenous in the 21st century, and why they chose to live where they do. It was to question whether a subsistence lifestyle can co-exist with a capitalist world.

Mary Demientieff at her fish camp along the Yukon River. The watershed is largely unspoiled by the effects of industry that have been keenly felt in other rivers, making the Yukon a rare environment for salmon to thrive.Ulli Mattsson

There has been a collapse of salmon across its entire range. Throughout Europe and Russia, up the east and west coasts of North America, the numbers are a fraction of what they once were. Alongside the raft of other pressures facing the salmon has been the decimation caused by dams, deforestation, pollution and fish farming (which transfers diseases and parasites to wild populations). At the start of the 20th century, 45 million fish swam up the rivers of Washington and Oregon and California each year; today, that number is two million.

Alaska is still known for its abundance of salmon, is still on the bucket list of every fisherman I know. But Alaska is special only because it is almost all that’s left. The Yukon remains the longest stretch of free-flowing water in North America (despite one small dam near the headwaters at Whitehorse) and is largely unsullied by the industry that rivers have been subject to elsewhere. As a result, the watershed retains the sort of pristine environment that salmon appear to demand. That makes the recent crash in numbers even more concerning, and harder to comprehend: Even some of the farthest-flung parts of the planet no longer seem impervious to the forces shaping the rest of the globe.

Fred Andersen, a former fisheries biologist, has called the Yukon River probably the most complex salmon fishery in the world. Teslin might sit 3,200 km from the Yup’ik village of Emmonak, Alaska, at the Yukon’s mouth, where the river stretches 11 km wide; but these two groups of people, although strangers, are intimately connected by the chinook, and there is profound distrust both ways. Those at the Canadian end of the river hear of commercial fishing at the mouth and feel resentful that someone is making a buck on fish that should be coming their way. Those at the mouth, in one of the poorest boroughs in the entire United States, wonder what the Canadians would do in their position, if there were no other jobs about.

Stephanie Quinn‐Davidson, who managed the chinook run for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game until 2015, told me that the vast majority of her job was communication – with other managers; with the media; and, most crucially, with fishermen. The chinook pass through a mosaic of state and federal land, and through the United States and Canada, each country with different divisions to its fisheries. Diplomacy between the United States and Canada is a further complication: The Yukon River Salmon Agreement, hammered out more than 30 years ago, requires that between 42,500 and 55,000 Chinook must be let across the border into Canada each year. This is a target that the United States has failed to deliver five times in the past 10 years.

The strict bans of 2014 and 2015, followed in the years since then by the permitting of very conservative fishing, have gone some way to stabilizing, and even slightly increasing, the number of fish returning. The chinook teeter on the brink, but however late in the day, fisheries management is waking up to this fact, long after Teslin and others first raised the alarm. Yet with “productivity” (the number of fish that come back for each spawning adult) still hovering near one to one, the whole system, if not yet imperilled, is extremely precarious.

What is needed, more than anything, is to get the weight of the fish back up. It is estimated that could take from 50 to 100 years, which is a long time to keep a strict fisheries policy in place. And it is a long time for cultures so bound up with the chinook to find alternative sources of sustenance, both nutritional and cultural.

Salmon can be brought back from the brink. Atlantic salmon are swimming through Sheffield in England since the rivers have been cleaned, after disappearing for 200 years. Salmon are back in Portland, Ore., and in Paris, France. There are not many, but it is a start.

And the future of the Yukon chinook does not seem hopeless, either, if reconciliation can be achieved. A reconciliation between commercial and subsistence fishing; between those who live at the river’s mouth and those who live at the source; between those who see their entitlement to food and wealth and culture swimming past them up the river and those who want a conservative approach, if not an outright ban on harvesting, forever.

A genuine approach to managing the chinook can only be holistic: one that involves the creation of an ecological web able to integrate culture and politics, histories and stories and beliefs. Nature is not “something else,” isolated, out there; it is as much a part of us as we are of it, and neither can be altered without impacting the whole. Whatever we choose to do, we cannot pretend that we did not know what was happening. What is certain is that, for the chinook at least, the Yukon is the last chance to get it right.