Members of the first Greenpeace voyage in 1971 before setting off from Vancouver for Amchitka Island, Alaska, to try to stop an American atomic bomb test.The Canadian Press

Barbara Stowe is the daughter of Greenpeace co-founders Irving and Dorothy Stowe.

September 15, 1971. My family of four is standing on Fisherman’s Wharf at Vancouver’s False Creek, in an activist crowd heavily bolstered by supporters and camera crews, watching history being made. Twelve men are about to set sail for Amchitka Island, Alaska, on the Phyllis Cormack, an aged halibut longliner. My father has hammered a sign on the bow, renaming the boat for the voyage, and Elaine Decker’s flag with the same new name – a canvas rectangle she sewed after her boyfriend Bill Darnell put “green” and “peace” together – flaps furiously from the mast.

Amchitka, born of volcanic fire, is situated in one of the most seismologically unstable regions of the planet. This is the site the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission has chosen for the biggest underground nuclear blast in American history.

While Pacific Rim countries nervously debate how to persuade president Richard Nixon not to detonate an atomic bomb in, basically, Russia’s backyard, and Indigenous and environmental groups launch lawsuits to halt Mr. Nixon’s nuclear bid, the Don’t Make a Wave Committee, a small Vancouver group, prepares to launch the Greenpeace.

The media is here in full force: UPI, ABC, CBC, the National Film Board of Canada and independent journalists have all flocked to Vancouver for this day, and the pier is so thick with cables it’s hard to walk around without tripping. My teenage brother backs up carefully, aiming his Super-8 movie camera at my father, and as a reporter shoves a fuzzy mike in Dad’s face, my mother and I move out of camera range.

Irving Stowe, right, was an original member of the Don't Make a Wave Committee (which would later become Greenpeace) along with Paul Côté, middle, and Jim Bohlen, left.Greenpeace

Dad’s smile is a ghostly grimace. We’re all of us faking it, wooden with dread. If the blast sparks an underwater quake, which generates a tsunami, the Greenpeace will be right in its path. Not to mention radiation exposure if the bomb shaft fractures, freak fall “williwaw” storms, or the questionable seaworthiness of the jury-rigged boat. The partners of the crew are having the worst time of it – for my family it’s “just” our friends going off to war. They’re pacifists, but there’s no such expression as “going off to peace” and what else can it be called when the battle lines are so clearly drawn? We – a volunteer muddle of flower children, journalists, engineers, Yippies, artists, community activists and students plus a teacher, social worker, lawyer and a doctor – are going up against them, the U.S. military industrial complex.

There is a clear enemy.

Or so we think.

Until 15 days later, when Commander Floyd Hunter of the U.S. Coast Guard cutter the Confidence boards the Greenpeace in Akutan, Alaska. By going ashore in Akutan and failing to make formal entry with customs, the crew is in violation of the Tariff Act of 1930. Captain John Cormack listens politely to Cdr. Hunter, while behind his back, three Coast Guardsmen pass a message to the Greenpeace crew:

“Due to the situation we are in, we the crew of the CONFIDENCE feel that what you are doing is for the good of all mankind. If our hands weren’t tied by these military bonds, we would be in the same position you are in if it were at all possible. GOOD LUCK. We are behind you 100%.”

Greenpeace's high-flying banners over the decades: On Halifax's Angus L. Macdonald Bridge in 1990, in a balloon above the Taj Mahal in 1998 and more than 1,000 feet up the CN Tower in 2001.The Canadian Press, AFP/Getty Images, Reuters

Greenpeace's actions have sometimes put them in harm's way. In 1985, French spies bombed the Greenpeace flagship, the Rainbow Warrior, before it could sail from Auckland harbour for a nuclear test site at Muroroa Atoll. A photographer drowned on board.AFP via Getty Images

A decade after the Auckland tragedy, the Rainbow Warrior II was back at Muroroa, where France planned to resume tests. Here, Phillip Papuka of the Solomon Islands steers an inflatable vessel away from the ship on July 6, 1995, three days before French navy commandos seized it and detained its crew.Steve Morgan/Greenpeace/The Associated Press

On Sept. 15 of this year, in muted pandemic fashion, Greenpeace celebrated a milestone 50th anniversary. It was a profoundly bittersweet moment. With 3.3 million supporters worldwide and offices in more than 55 countries, the little ragtag group has become arguably the biggest eco-justice organization on the planet, a success story by any reasonable standards. On the other hand, Jennifer Morgan, executive director of Greenpeace International, spoke for all of us when asked what lies ahead: “I guess the goal would be that Greenpeace doesn’t exist anymore.” As the world floods and burns, there’s no joy in correctly predicting climate crisis – only a desperate desire to stop it.

In times like these, it’s essential to reconsider any preconceived ideas about the enemy. This year, the organization has been re-examining itself: revisiting the past, considering the successes and failures of five decades and trying to plan for a future that no-one can predict. As I spin down memory lane with others from the founding days, the voice of my late father booms in my ears: “The people must take back the power over their lives!”

Yadda yadda, I used to think as a teenager. How could a group of pacifists fight the mighty U.S. military industrial complex? I’d shrink back against the wall of Birks jewelry store at Georgia and Granville in the hub of downtown, as the rest of my family, and fellow Quaker activists Jim and Marie Bohlen, and Bill Darnell sallied forth to hand out petitions and sell buttons. Lance Bohlen, my age, shrank back with me and I sensed a kindred spirit with the same horror of approaching strangers on a street corner. But when we sold a few buttons and made a few dollars toward saving the world from nuclear madness, the way he pulled himself up to his full six feet showed that he felt as chuffed as I did. At those times we were brave. I liked the feeling of being brave.

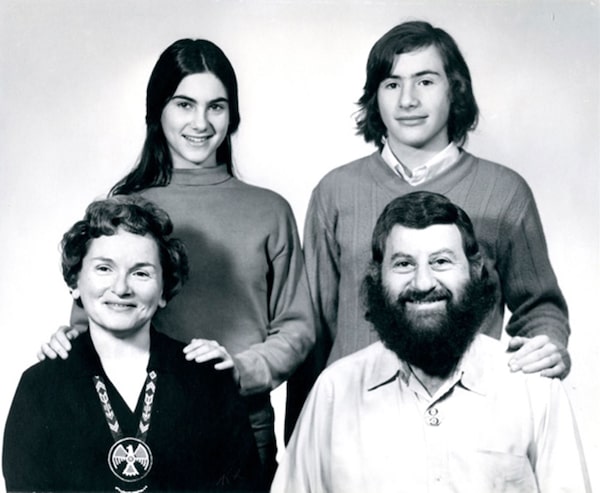

The Stowe family, clockwise from top left: Barbara, her brother Bobby, father Irving and mother Dorothy.Photo by Ken McAllister/courtesy of Barbara Stowe

Our home in West Point Grey functioned as the first Greenpeace office, but after my father died in 1974 of pancreatic cancer, the organization moved out. My brother and I moved out too – Bobby went to Eastern Canada to study physics, and I went to New York (where no one had ever heard of Greenpeace) to dance. I was trying to communicate something ineffable, something that offered respite from the troubles of the world. I longed for that respite.

Then, in 1986, when a friend drew me into the Vancouver Peace Flotilla, and with fellow activists we witnessed the breakdown of the same boundaries between “them” – the military – and “us,” a pacifist contingent. In kayaks, canoes and sailboats we rode out to greet U.S. warships as they arrived in Vancouver, and our signs proclaimed that while the navy was welcome, nuclear missiles were not. The sailors, resplendent in white uniforms, stood on multiple decks in an impressive formation that brought to mind a well-disciplined corps de ballet. Many flashed us peace signs, and as they came off the ship I approached one, not without trepidation, to ask why he flashed the “vee.” He grinned and spoke first: “We don’t want to be sailing with nuclear missiles either.”

A walrus sits on ice in the Chuchki Sea between Alaska and Russia in July of 1999 as the Greenpeace icebreaker Arctic Sunrise sails in the distance. Scientific expeditions such as this one gathered evidence of how climate change was affecting ecosystems.Daniel Beltra/Greenpeace via REUTERS

At left, Patrick Wall of Greenpeace puts dye on a harp-seal pup in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1982; at right, activists demonstrate on Parliament Hill in 1992 to oppose overfishing off the Grand Banks. Greenpeace's stands against seal hunting and industrial fishing sometimes put them at odds with communities whose livelihoods depended on those activities, such as Indigenous People in the North.UPC, Reuters

In the summer of 2007, John Hocevar, oceans campaigner for Greenpeace USA, initiated the “Bering Witness” tour. Despite scant contact with Greenpeace since the early days, I found myself joining a 26-person crew on the Esperanza for three weeks. The newest boat in the now-international organization’s fleet, a former Russian navy ship with five Zodiacs and a helipad, was a far cry from the rickety Phyllis Cormack with her lone dinghy.

This was just the beginning of the shocks in store. My deeply ingrained perception of “the enemy” was about to be challenged anew.

The mission took us to coastal communities to record locals’ experience of what factory fishing and bottom trawling were doing to the marine environment. Greenpeace wanted to work in partnership with these communities to pressure government to create marine heritage zones and institute other preservation measures.

Greenpeace Alaska campaigner George Pletnikoff – native to this territory, and a former Russian Orthodox priest – came aboard at Dutch Harbour to lead the mission with John. It had taken Greenpeace a year to persuade George to take the job, and as we sailed through the Unangan islands the Russians had renamed the “Aleutians,” we’d soon see the reason for his reluctance.

At Adak, a U.S. military base slated to be closed, two young mothers brought seven children to “Open Boat.” With recreation facilities shutting down, visiting our ship was a rare break from boredom, and Greenpeace colouring books were welcomed. That parents whose livelihood depended on the armed forces would freely expose their children to pacifist influence surprised us. In the Boop café (named for Betty Boop), a Filipina working behind the counter asked, “Are you with the Greenpeace boat? Do they have any job openings?” Servicemen stopped us on the street to invite us to a barbecue, and ask if Greenpeace was hiring.

None of these people were the enemy.

We went to St. George, one of the four Pribilof Islands that sit magnificently isolated in the middle of the Bering Sea, and as we puttered to the dock in Zodiacs we caught a brief glimpse of the life of the roughly 120 humans who populated this place. An Unangan man stood on a green hillside, smiling at Mr. Pletnikoff, putting a closed fist over his heart, and George responded in kind.

Meanwhile a boy running down the hill was shouting: “George! George!” He was so excited he tripped and fell, but picked himself up and kept running as George waved back. A younger child on the shoreline plucked something from the water, and the running boy, reaching him, tried to grab it. “I want that sea urchin for my crab traps!” he said.

A woman gently chastised him. George later introduced her as the boys’ mother but I was only half present, still digesting that for children here, sea creatures were no curiosity but an essential ingredient of their culture and daily survival.

A big bear of a man with curly black hair and the warm brown skin of the people who’d lived on these islands for thousands of years, George had superb comic timing that kept us all laughing.

But as the hour of a tribal council meeting approached he turned sombre. The people of St. George were deeply suspicious of an organization that had campaigned hard against seal-hunting, a mainstay of their culture and crucial to their survival. They were especially suspicious of their former parish priest-turned-environmentalist who was now considered by many to be “the enemy.”

After sitting through the tense tribal council meeting in the morning, we went to an evening community assembly in a packed hall. The air was icy with hostility. George set up a big screen and showed video footage of the tracks the bottom trawlers had scraped into the ocean floor. A woman sitting beside me leaned over and whispered: “It looks like a road.”

Then George screened interviews the campaigners had shot in other coastal communities. In one clip, an Indigenous woman spoke of how she knew, from the quantity of fish her mother was drying and storing, that the time was coming when “our people will starve.” She sobbed, unable to continue. The room had been steeped in a mistrusting silence, but now the energy shifted as a mutual empathy and grief began to break down the edges of the boundary between “them” and “us.” When the film finished, George turned on the house lights and began a Q & A, and the boy who’d run to greet him at the dock raised his hand. “Is our culture dying?” he asked.

George’s whole body sagged. “Don’t you worry about that,” he said, but it was obvious what it cost him. “You let us worry about that.”

As the Q & A progressed, it seemed the community was beginning to believe that Greenpeace was not here to criticize Indigenous hunting practises, but to support Indigenous culture and forge an alliance based on environmental preservation, until a middle-aged man raised his hand. “What about me?” he asked. “I work on one of those bottom trawlers. It’s my livelihood.” He was looking at me. My insides roiled. George had introduced me as the daughter of Greenpeace founders, and I stumbled through a lame response thinking, there is no answer to this question.

The answer came after the meeting, when he approached George to warn him to expect a difficult reception from the people of St. Paul, the next island we’d stop at, and suggest how to appeal to the community there. I realized he was supporting our campaign even though it threatened his livelihood. Years later, still trying to process this, I told a relative who put it in perspective: “He’s bigger than his job.”

A cement pad, buckled by an underground nuclear test, and a derelict Second World War cargo plane are seen on Amchitka Island in 1971. Thirty-six years later, Greenpeace members would see Amchitka again on the Bering Witness tour.The Associated Press

Unfettered capitalism, consumerism and a disconnect from nature has created the current climate crisis, with its increasing catalogue of disasters. Naomi Klein nailed the necessary road ahead with a vision for a sustainable future when she said: “The task is clear: to create a culture of caretaking in which no one and nowhere is thrown away, in which the inherent value of people and all life is foundational.”

The gap between where we need to be and the current road that, if followed, will destroy us was illustrated – along with a partial answer to the question “who is the enemy?” – by a sign we saw when Captain Pete Willcox brought the Esperanza alongside at Constantine Harbour, on now-deserted Amchitka Island. This was our final destination, the last port of call before heading back to Dutch Harbour.

The day before we’d dropped anchor on the other side of the island and beach-landed in an eerie silence. Where were the sea otters that once played around these shores, in what used to be the only designated sea otter sanctuary in the world? Where were the puffins and red-legged kittiwakes, the teeming colonies of fur seals and sea lions that populated the coasts of other islands we’d stopped at? Amchitka appeared deserted, and not just by the military but all living, breathing creatures.

We hiked through muskeg to the shores of Cannikin Lake – the 30-acre body of water the US Atomic Energy Commission accidentally created by exploding the bomb code-named “Cannikin” and, as one fisherman at St. Paul had put it, “blowing the chit out of Amchitka.” Six lakes on the island disappeared then, only to reconfigure themselves by some strange dark magic, reappearing in the deep cavity above the borehole where a substantial part of the island had imploded.

On the boggy shore of Cannikin Lake, I knelt and peered into the ground cover – there was plenty of that, true, a thick green spongy carpet, barring the occasional barren patch – and parted the vegetation with my fingers until finally I found something moving. It was small and black and I didn’t want to get too close.

“Look,” I called to the ship’s doctor, Clive, a fervent naturalist. “What is that? A spider?”

He bent down. “Yes.” Several engineers crowded in to see. One, Slava, held out his wrist to the spider. “Bite me,” he said, referencing Spider-Man, and we all laughed darkly.

Now, the following day, on the other side of the island, we stood on a weather-worn dock looking at a small sign that announced: “Office of Legacy Management.” It had an atomic symbol on the left-hand side and two fir trees on the right. In the middle, on a stylized image of a white, winding road, stood a man, holding the hand of a small child. The implication was clear: The Department of Energy’s Office of Legacy Management was a caring, protective arm of a government that had paved a safe and trustworthy path to the future.

Only something was wrong. This father was turned fully away from his child, looking in another direction, disconnected, out of touch. His hold on the child’s hand appeared tenuous, as if he was about to let go or had forgotten the child was even there. This was the true legacy of nuclear weapons that blow things, people, worlds apart. This was an institution going down the wrong road, driven by a dangerous, arrogant, blind, paternalistic, patriarchal disregard.

A logo for the Office of Legacy Management shows a parent and child on the road together, suggestive that the U.S. government agency has made a path for generations to come.Courtesy of Barbara Stowe

In one of this summer’s global Zoom calls with Greenpeace staff, Ana Toni, former board chair of Greenpeace International, spoke passionately about the need for the organization to work harder to engage with people whose work impacts climate change negatively, to see if there’s anything Greenpeace can do for them.

Of course she was by no means implying that Greenpeace could possibly supply jobs for every worker who might want to change direction – whether they be military personnel such as those we’d met on Adak, men toiling in the tar sands of Alberta or loggers of old growth forest in Vancouver Island’s Fairy Creek who might be conflicted about the effects of their work. Greenpeace, supported by donations, not governments, doesn’t have the resources to offer many new jobs. But one thing the organization does do is to model another vision of “work.” Because as the effects of climate change hit home, increasingly the public is willing to support environmental and social justice advocacy groups, trusting them to employ campaigners and scientists and engineers to do what governments are not doing, to create green technology and pressure industry to change before it’s too late. Creating “Greenfreeze” refrigerators, training thousands of volunteer firefighters in Russia, all this is now essential labour. Countries will always have armies. Greenpeace offers a different kind of defence work.

Sipping Alaskan Summer beer in a bar with my shipmates on St. Paul, the island we stopped at after St. George, we listened to a hulking fisherman bemoan the damage factory fishing and bottom trawling has done to the marine habitat. “Greenpeace is 20 years too late!” he roared, pounding a meaty fist on the bar, making glasses jump. A minute later he grunted, “I may not always like what Greenpeace does, but if it wasn’t for them, there’d be no boreal forests in the Amazon.” Later still he added: “My buddies and me refused to work on Amchitka. It’s radioactive.”

When jobs destroy people and the environment (a false separation, the two are inextricably linked) we need systemic change. And in 2021 the need for systemic change couldn’t be more urgent. As climate justice activist Aneesa Khan has pointed out: “Climate change isn’t something in the future. That narrative is fundamentally flawed, because there are millions impacted and so many displaced already.”

Climate action through the years: At top, a Greenpeace activist dressed as a polar bear suntans on Parliament Hill in 2007, with a sign referring to the Kyoto Protocol on greenhouse-gas emissions; at bottom, Montrealers take part in a climate protest this past Sept. 24.Tom Hanson and Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press

My father’s words, “The people must take back the power over their lives,” reverberate ever more strongly as the climate crisis escalates. In 2014, on Burnaby Mountain, I watched police arrest Bill Darnell – the man I call “Uncle Bill,” the quiet man who sat in meetings in our living room when I was a teenager, the man who greened peace – for non-violent protest against the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project. Two years later, moved by the action he and his fellow arrestees – including a Canadian soldier and a 13-year-old girl – took, and by the eloquent oratory of the Tsleil-Waututh elders, and by the many reasons so many people were standing against this project – I zip-tied myself to the Kinder Morgan tank farm gate with Greenpeace founder Rex Weyler to oppose the same project.

My brother joined us. It was standing room only at our first court appearance, the room packed with many more arrestees than there were seats. Bobby and I hadn’t held hands since we were children, but as Justice Kenneth Affleck lectured us all for violating the injunction he’d awarded to Texas oil giant Kinder Morgan, we instinctively reached out to support each other.

At our second appearance, Indigenous defendant Kat Roivas schooled His Lordship in colonialism: “You may be a lord but you are not my lord,” and defendants started rising, hands in the air, blessing her in the traditional First Nations manner. I rose too, nervous and defiant, knowing we might be cited for contempt. There are some things that even a reluctant radical will put that most valuable of all assets, personal freedom, on the line for.

Greenpeace co-founder Rex Weyler, sitting beside Barbara Stowe, is arrested by RCMP officers after he tied himself to the front gate of the Kinder Morgan facility in Burnaby, B.C., in 2018.Ben Nelms/The Globe and Mail

This spring, almost 50 years after the Phyllis Cormack sailed for Amchitka Island, five of us from the founding days received an extraordinary e-mail. Robert Keziere – whose photographs in The Greenpeace to Amchitka (co-created with Robert Hunter) brought the crew’s experience vividly to life – had received permission to forward a narrative written by Steve Todd.

It was Mr. Todd, we learned, who’d initiated that subversive note of support in 1971. After a nudging from his youngest son, he’d put his experience down on paper.

His sons knew the tale from bedtime stories Mr. Todd had culled from his Coast Guard career. All the stories had titles like, “When Dad got sick,” or “When Dad saved the Captain,” and the longest and most requested story was: “Sometimes it’s okay to break the law.”

Mr. Todd’s reaction on seeing the boat gave us the moment through his eyes: “It was very exciting to finally see exactly what the highly tracked and much publicized vessel looked like. I was the officer of the deck on the anchor watch and knew that the Captain intended to board the Greenpeace by evening to deliver the customs warning.” He thought about sending the crew, “a kind of a thank-you note, so to speak. After all, who could appreciate what they were doing more than us, Coast Guards who had been in the Alaskan weather and out on these waters every day and knew the risks they were taking to make an honourable voyage.

“I turned to mention this to Ken Grushoff, the first class ET, and he said to me, ‘Todder, I will get right on that!’ ”

Crewmate Andy Hrizuk dictated the message that 18 men signed.

When Mr. Todd and his crewmates found out that the note had become international news, “The high anxiety commenced for me! I left the Confidence and made my first and only phone call out of Alaska, to my dad and said, ‘I might be going to Portsmouth [naval prison].’”

His father had done something similar in the Second World War, following his conscience, and replied, “You gotta do what you gotta do.” These were reassuring words.

Later that night, over gin and tonic, Mr. Todd and Mr. Grushoff agreed that if they had it to do over again, no matter the outcome, they would have made the same choice.

It was public knowledge that 17 of the men who’d signed the note had been fined $15 to $100 or received suspended busts. But it was news to hear that, as the only officer to sign, Mr. Todd had been punished more severely.

Found guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, he received three days restriction and a Letter of Reprimand. “Pretty much a career-ending service record document.”

And after three days, he was put back on the job. Which raises the question of subversive support from those higher up the chain of command. But the most startling revelation in Mr. Todd’s text was this. The day the Atomic Energy Commission exploded Cannikin, “The seas came up 50 feet. ... We ran before the sea north for 50 miles plunging our bow into the mountainous waves ... the whole ship shuddering as we rose up rolling and burying the air castles and taking green water over the flight deck. I thought how providential that the Greenpeace was not in this sea.”

By serving Capt. Cormack with the violation order that forced him to turn back, had the U.S. Coast Guard, an arm of the U.S. military, actually saved the lives of the entire Canadian Greenpeace crew?

Had the enemy saved its nemesis?

No. Not its nemesis. Because it was never “us against them.” There are hidden allies, points of solidarity between apparent opposites. In 2021, it’s Greenpeace’s job to increase this solidarity. The fact is that the 3,532 staff the organization employs would gladly seek other employment if only there were no need for the goals laid down in the original constitution, goals Greenpeace is still pursuing today.

Progress has been made toward those goals. The first, to stop nuclear testing worldwide, was addressed in microcosm when the U.S. quietly cancelled the Amchitka test series several months after the Greenpeace set sail, and in macrocosm on Jan. 22, 2021, when the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons came into force. Credit for the latter, landmark achievement goes to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, but groups like Greenpeace, which have been campaigning against nuclear weapons for decades, have had a significant impact. All hands are needed on deck. As for the second goal, “preserve the environment,” this, too will come down to solidarity. Millions of young people, led by Greta Thunberg, have joined student strikes for climate action, and as settlers join forces with Indigenous activists and get woke, the combined resistance to the forces that are destroying us become stronger. Recently, Bill Darnell, on evacuation alert this summer as fires ravaged forests near his home town of Vernon, B.C., patiently echoed once more the blindingly obvious: “There is no longer any ‘soon’ for climate action. There is only ‘now.’ ”

From the archives: A Greenpeace family story

From the archives: A Greenpeace family story

Globe and Mail journalist Justine Hunter is also the daughter of a Greenpeace co-founder, the late Robert Hunter. In 2015, she visited a Kwakwak’wakw community to stand in his place in a ceremony – and let go of her grief

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.