ILLUSTRATION BY SANDI FALCONER • PHOTOS COURTESY OF COREY MINTZ

Corey Mintz is the author of How to Host a Dinner Party and host of the Taste Buds podcast.

Every superhero has an origin story, and so does every comic-book collection. Mine grew out of a conversation at recess one May afternoon in 1984, when my friend Anooj asked what I was getting for my ninth birthday, which I would celebrate later that week. Every Saturday, I watched the cartoon Spider-Man and his Amazing Friends, waiting for a repeat of my favourite episode, featuring a team of heroes called the X-Men. Anooj informed me that there was a comic that was just about the X-Men and that they also starred in another comic called Secret Wars, which featured the most brilliant idea a nine-year-old could imagine: A magical being makes every superhero fight every villain for no particular reason.

I was hooked.

From that point on, I went to the comic-book store every week, my collection growing inside a drawer in the bedroom I shared with my brother, later migrating to a closet shelf, then a box designed for comics, which multiplied over the years into 17 boxes holding about 2,500 comics.

Three decades later, I got married.

Whether you divide our opposing tribes along lines of aesthetics (tidy versus sloppy), values (spartan versus packrat) or class (snobs versus slobs), there is no denying the world is divided into neat people and messy people. We don’t change teams. But we do intermarry. And we have to learn to live in peace.

And whether you are Napoleon and Louis XVIII signing the Treaty of Paris (1814), Lucy and Ricky drawing a line down the centre of the apartment (I Love Lucy, Season 1, Episode 8, 1951) or Darkseid and Highfather placing their children in each other’s care to prevent war (New Gods #7, 1972), all of history’s greatest armistices are about division of territory.

So it was with my comic books.

Corey Mintz lives in a Toronto loft apartment with his wife, Victoria.

Victoria rests on the couch. Discussions about how to use the shared space – and what to do with Corey's large comic-book collection – took on a growing importance in their marriage.

Victoria and I live in a loft apartment, with one large open space for our kitchen, living room, dining area and gym.

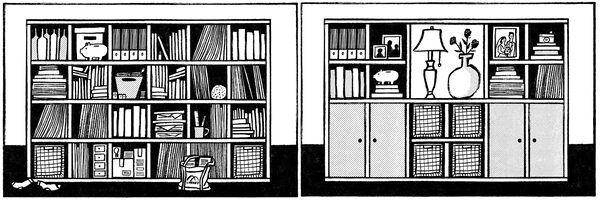

Our bookcase is nothing special. It’s the same collection of IKEA Kallax interlocking units that everyone has – except that thanks to our high ceilings, we’ve got 72 of the cubby-hole cubes. Until recently, my comic books took up 17 of them.

In addition to comics, there are spaces for cookbooks, wine, my rubber-band ball, her ballet slippers, spare light bulbs, a canister of compressed air, board games, photos of our grandparents, a box of candy bars my wife doesn’t know about and camera gear, among other things. While she has shelves for purses and gym equipment, my possessions clearly dominate. She’s never minded, since about the same amount of wall space is taken up by her open walk-in closet, three clothing racks all in a row.

IKEA Kallax interlocking units are stacked high on the walls of Corey and Victoria's home.

Over time, though, I started to notice strange activity on the shelves. When Victoria finished a book, she would bring up another half-dozen from a bookcase in the lobby of our building, where people dump their old novels. She’d choose one to read, then wedge the rest into open spaces on our shelves. Gradually, each square became double-parked, with random unread books – other people’s junk – filling up our space.

Meanwhile, the drawer under the bathroom sink filled with bottles of creams and lotions – some highly valued and used every day, others almost empty and abandoned. The shelf underneath the coffee table, meant for remote controls, swarmed with nail polish bottles.

Every time Victoria proposed a new item for our home – a second-hand treadmill and steamer I would come to use regularly – I opposed. I knew I would eventually give in, but I needed to stem the tide of detritus flooding our home. She countered by proposing we put our dining room chairs in storage, or perhaps get rid of them altogether, along with the dining table.

One day she came home with a fourth clothing rack in a box – a “day rack” to be used exclusively for assembling the week’s outfits. I suggested that if she wanted to highlight clothing, subtraction might work better than addition; that getting rid of overstock would have a more positive effect than enlarging the showroom.

She did not want to hear that. But at the time we were fostering three kittens, so it wasn’t a good moment for her to argue in favour of bringing more things into the home. And I didn’t argue with her because my mission is always to stay married, which means not fighting every conflict as it arises, trusting that some things aren’t worth it, that sometimes they take care of themselves.

Two of the couple's foster kittens get up to mischief beside a rack of clothes.

Last year, we took a trip to Italy. In a twist as shocking as discovering Magneto is the father of Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, a few days after we returned home, Victoria removed a third of her clothes from the racks and donated them to Goodwill. To this day, the fourth rack remains in its box, on the floor where she first placed it. With fewer items on the racks and floor space cleared by the elimination of shoes that the kittens had peed on, she remarked on how she could clearly see the clothes she truly loved, how much more it all resembled the curated display of a well-lit store.

I chose this moment to tell her that I was planning to get rid of some comic books. This would free up space on our bookcase, but I cautioned that it was not simply to be refilled with random junk.

Later, when my friend Max came to town, we made a night of going through the collection, pulling out the comics from each box and subjecting each to the core question of home-organizing guru Marie Kondo, “Does it spark joy?” before adding them to a discard pile. We tacked on a few qualifiers of our own. Would I ever read it again? Would I recommend it to someone else? Would I be embarrassed if someone saw it on my shelf? Does it have genuine sentimental value? Does it have monetary value?

The problem was that they all had sentimental value. I had been collecting these things since I was 9. But whether it’s the rice pasta in the pantry or a near-complete run of Kamandi, The Last Boy On Earth, you know when you have no use for something.

Many of the rulings were obvious. Runs of Fantastic Four and Spider-Man from the 1960s, stuff I continued to reread over the years, were going to stay. Much of the rest was on the chopping block. We deliberated over the small details.

“This is a great comic,” Max said, holding up the first issue of Jack Kirby’s Black Panther. I countered that since I gave up my back-issue crate digging years ago, I was never going to buy the other 12 issues; besides, it was now easy to read complete stories through collected editions or online subscriptions. I felt protective of some Art Adams comics – until Max pointed out that perhaps my 13-year-old self only ever liked the women drawn with impossibly tiny waists and large breasts. Embarrassed, they went immediately to the discard pile.

When in doubt, I invoked two precedents established by author/podcast judge John Hodgman: It’s reasonable to save objects purely for sentiment, but apartment dwellers must limit this to no more than the volume of a shoebox; and the difference between a collection and a hoard is that a collection is used or displayed.

In the end, I cut about 900 comics, 35 per cent of my collection. Every time I excitedly told someone about my culling of the herd and the shelf space it would create, they were enthralled at the jackpot I was sure to reap. Many former comic buyers think they’re sitting on a paper gold mine, but our collections aren’t worth anything. At least not what we are led to believe.

Shortboxes of Corey's comics are stacked on the floor. At the top is an issue of Mister Miracle #1, written and drawn by legendary artist Jack Kirby.

Growing up in the 1980s, I repeatedly heard an urban legend about a guy whose mom threw away a fortune in comic books when she cleaned out his old room, the basement, attic or garage. There was some basis of truth to this. Because for the first 40 years of the medium, comic books were disposable. Kids rolled them up, stuffed them in their back pockets, read them, traded them and tossed them aside – only the true obsessives saving them to reread. Part of the reason there are so few copies of Superman’s first appearance from 1937 is that a lot of “golden age” comics didn’t survive the paper drives of the Second World War, when newsprint was recycled in a conservation effort.

As with coins or stamps, there is value in rarity. So there was always someone on the lookout for hard-to-find comics. But organized collecting didn’t start until the late 1960s, when Marvel readers, just trying to track down a five-year-old issue of Spider-Man to complete their runs, began to notice used book dealers commanding high prices for even “silver age” comics. Around this time, conventions evolved out of the “rummage sales” held in church basements and libraries. A far cry from today’s glitzy affairs, where movie studios launch their marketing campaigns to fans dressed in costumes, nascent conventions were held in hotel ballrooms and were often the only opportunities for collectors to buy and sell, as well as meet each other.

In 1970, the first edition of the Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide was published, soon to become a collector’s bible, with its detailed evaluations for fair-, good-, near-mint- and mint-condition comics.

By the late seventies, the legend of the lost collections grew, as many baby boomers returned from college to find their parents had emptied their bedroom closets, stacks of Avengers and Daredevil comics dispersed for pocket change through yard sales.

That’s why, when I was growing up, everyone knew someone who shared a version of the squandered-fortune story, often with a touch of misogyny mixed into the tale of a cousin or uncle who could have bought a house if his foolish mother hadn’t thrown away his buried treasure (somehow, despite the odds, I’ve never heard a version in which it’s the dad who cleaned out the basement or garage).

These legends, and a fundamental misunderstanding of how market scarcity works, spurred collectors to “bag and board” every 75-cent issue of Teen Titans, sheathing them in protective plastic sleeves and strips of cardboard. Comic-book stores over-ordered, believing they would continue to sell back issues to collectors for years to come. In the 1990s, the floundering comic publishing industry seized on this misconception by producing variant covers of new editions so readers would buy multiple copies as investments.

If you’re a financial trader or a chef, you know that adding volume to a stock dilutes its value. But try telling that to a 13-year-old who thinks they’re buying a blue-chip stock at a dollar a share. Either way, if you’re currently sitting on a bunch of Punishers from the nineties, they are destined for the 50-cent bin.

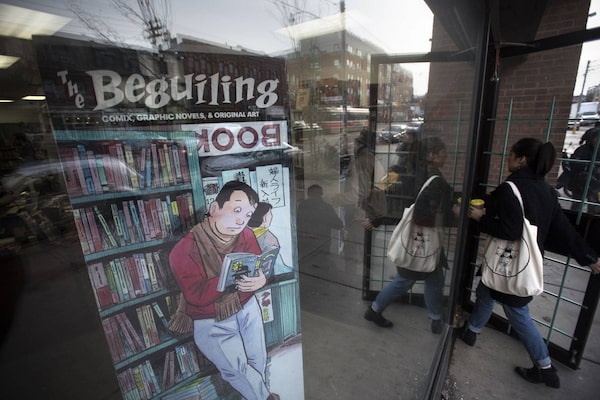

Still, even though I knew the collection wasn’t worth much, I’d told the staff at The Beguiling comic-book store that my “go pile” contained a significant amount of 1970s Jack Kirby material, so they offered to take a look.

Usually, the shop just offers sellers a price, in cash or store credit. Providing me a peek behind the curtain, they shared a spreadsheet, with a separate column for grading (an estimate of physical condition, on scale of one to 10), potential retail price for resale, the percentage of that price offered to me based on the likelihood of selling the item (18 per cent for the first Kamandi versus 30 per cent for Black Panther), the price offered to me, then a final column for important notes such as “first appearance of Darkseid” or “death of Gwen Stacy.”

I was thrilled to see any money, satisfied simply to have the junk off my hands. Even the lowest-value stuff, at five cents apiece, was better than having to drag it to Goodwill myself.

“In a city like Toronto,” says Peter Birkemoe, owner of The Beguiling, “the limits of space are what end up causing comics to be sold, not the need for money.”

Corey went to The Beguiling comic-book store in Toronto to offload his 'go pile' of books.FRED LUM/The Globe and Mail

Six spaces freed on our bookcase, I made a tactical error. With the overconfidence of Lex Luthor, I boasted to my wife of how I’d vanquished the shelf space. Rather than immediately reorganizing and finding a use for each slot, I revelled in their emptiness before leaving on a work trip.

When I returned, Victoria was also away on her own work travel. Three of the shelves had been filled with random items – a travel neck pillow, scrunched up plastic bags, loose batteries and unread books that had previously cluttered her bedside table.

Victoria works for UNICEF and was at that moment in Uganda, at a refugee settlement near the border with South Sudan. It was not the right moment to message her about my need to keep the bookcase organized.

Instead, I got to work on the shelves. I bundled all the cords for computers, phones, cameras, storage drives, microphones, etc. into a box. I moved the pasta roller to where it should be, in the kitchen, to make space for a toolbox. Wrapping paper, bows and tape got folded into a lunchbox and placed next to the one with office supplies.

As I went over the shelves again, I noticed how throwing out something I thought was precious made it easier to throw out everything.

It became easy to earmark more items – books, comics, DVDs – for the donation pile. But I couldn’t touch Victoria’s belongings. You can’t throw out someone else’s property. What you can do, however, is show them how much you are getting rid of, then open up a box that contains cords and charging pods for cameras that she hasn’t seen since her undergraduate years. And if you have a partner who has devoted the past decade of her life to visual storytelling, you can trust the science of “show, don’t tell”: The visual impact of so much forgotten and obsolete junk will convince her that she can make more cuts, too. And eventually, you will both delete enough items that you are more comfortable in the home you share.

Our shelves look nice again. The dining room and kitchen tables are clear, no longer repositories for whatever came into the home that week. They’ll be messy again. Because we are human. And at the end of the work day, we are too tired to dogmatically adhere to Marie Kondo’s cleanliness doctrine. New piles of junk will grow. It’s my job to prune those piles to keep them from becoming mountains.

Tidiness is an everyday affair. One does not have a neat home, one keeps a neat home.

And if you are like me, the Felix to your partner’s Oscar, there is only one way to have a clean home: Clean it. Sweep, mop, dust, wipe, scrub, tidy, organize, reorganize. Do that and your home will be neat. It helps if you like cleaning and/or podcasts.

Here’s what you don’t do to achieve a clean home: nag, guilt, pressure or in any way ask your partner to change or feel bad about who they are. That’s who you decided to be with. And love cannot be conditional on our demands that people change.

We both knew who we were marrying. And while both of us have changed dramatically into more thoughtful and patient versions of ourselves, learning to compromise on big-ticket life items, she’s never going to start squeezing the toothpaste from the bottom of the tube and I’m never going to stop caring. So every time I find a five-day-old, lipstick-marked can of strawberry daiquiri in the fridge, with two sips left, I think of how she kisses me goodnight. Every time my toes touch crumbs in the bed, I remember how she says “I love you” as she leaves for work in the morning. And every time a new book, energy drink or pair of shoes arrives in our home, I remember how she arrived in my life and made it infinitely better.