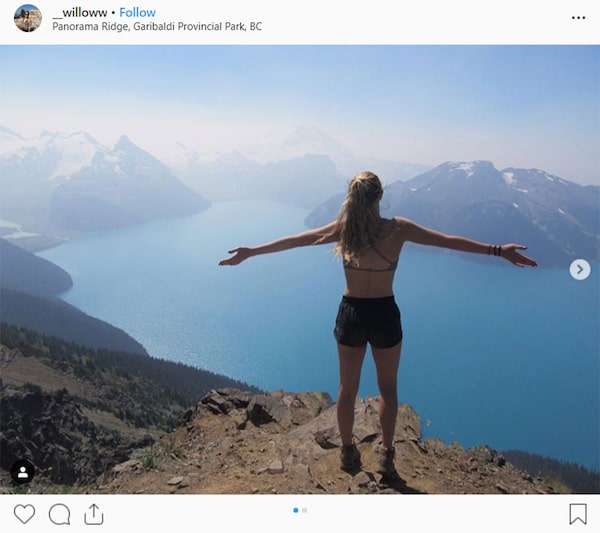

It takes a 30-kilometre round trip hike to reach Panorama Ridge in B.C.'s Garibaldi Provincial Park, but Instagram has plenty of posts from those willing to make the journey for a perfect view.Instagram (@seni_sk, @meganeastwood, @courteneymichelle)

Mélissa Godin is a multi-media journalist who reports on gender, climate change and human rights. She is a Rhodes Scholar, a National Geographic Explorer, and a GroundTruth Project Fellow.

A few weeks ago, my friends and I tried to reserve a camping spot at Garibaldi Provincial Park in British Columbia, only to discover that it was completely booked until early October.

For the past few summers, I have made a yearly pilgrimage to Garibaldi Lake, reserving my camping spot five minutes before arriving at the head of the trail. Although Garibaldi is one of B.C.’s pristine provincial parks filled with glacier lakes, windy hiking paths and snow-capped mountains, it can be difficult to access. Getting to the picturesque Panorama Ridge is a 30-kilometre journey round-trip, which even for avid hikers can be quite tiring. And yet, this summer, the trails were busier than I have ever seen them. Hordes of people wearing everything from hiking boots to platform heels climbed the path to the lake to get their well-earned photo next to the crystal blue water.

The number of visitors to the outdoors has hugely increased in the province. This year, B.C.’s parks have been visited 4,928,500 more times than they were in 2014-15. For outdoorsy British Columbians, this increase is extremely evident: Quarry Rock in Deep Cove is now monitored by a ranger to ensure that only 70 people are on it at a time and it is next to impossible to get a parking spot in front of Joffre Lakes.

The increase in visitors is in part a result of initiatives by the provincial government to boost tourism to B.C. According to The Walrus, Destination BC – a provincial tourism agency – receives $51-million a year to promote the beautiful outdoors. Their strategy involves paying social-media influencers to popularize various parks around the province.

Many in the outdoor community are upset that their favourite spots are now packed with visitors and frown upon anyone that geotags their hiking locations. Experienced hikers argue that Instagram has resulted in people going outdoors for the wrong reasons. Frustrated by the rise of “insta” tourists, an anonymous 31-year-old man from Idaho created an Instagram account called Public Lands Hate You. At the time of writing, his bio reads “people ‘doing it for the gram’ are prioritizing profit, fame, and ‘rad pics’ over the health and future of our favourite places. Who else is fed up?”

A post on the Public Lands Hate You account calls out hikers for ignoring signs and going off-trail to get pictures of wildflowers.Instagram (@publiclandshateyou)

According to these critics, people are going outdoors to get the perfect photo for Instagram rather than to appreciate the quietness of the forest or the sweet smell of red cedar trees.

To an extent, people such as the man behind Public Lands Hate You are accurately identifying a change in the way people behave in nature. I was shocked last summer to arrive at the third Joffre lake to find a woman lying on a rock, posing in a silk dress. Photos of parks are being posted at an unprecedented rate and Instagram influencers are capitalizing and commercializing nature. As a result, it is fair to question whether people are going outdoors for fresh air or for the likes on Instagram. But in other ways, the growing popularity of nature may be a result of the outdoors becoming more accessible.

In Canada’s recent history, some of the country’s most beautiful parks have largely been enjoyed by the middle and upper classes. A tour guide at Banff National Park told me that the area was originally frequented by rich Europeans who paid upward of $35,000 for a month of vacation in the great Canadian wilderness.

Today, many of Canada’s most beautiful outdoor landscapes are more readily available to the rich who live in proximity to these places or can afford to vacation in them. In Vancouver and its surrounding areas, for instance, many of the best hikes are situated between the North Shore and Whistler – two of the most expensive cities in Canada. The people who have access to these free hikes – who can squeeze it in before or after work – are those who live in these affluent areas. “Where do you ski?” is the ultimate class question in Vancouver, with the rich typically gravitating toward Whistler, where a one-day lift ticket costs upward of $100.

A ski day in Whistler.Instagram (@evanmceachran)

I developed all my outdoor skills while participating in mandatory camping trips with my private school. Each student was expected to buy loads of gear that cost their parents a small fortune. Every September, we – a group of smelly, privileged preteens – would set out into the forest with heavy backpacks and polyester clothing. We learnt how to purify stream water and hang our bags of food in nearby trees. When we became young adults, we knew where and how to camp: We had camping stoves and dry bags in the back of our closets.

This is not to say that class is the sole indicator of whether someone will be “outdoorsy”: There are many low- to middle-income communities throughout Canada that regularly engage with nature. On the whole, however, Statistics Canada found that “households’ participation in outdoor activities close to home increased as the annual income increased, from 56% for those with annual incomes of less than $20,000 to 88% for households with annual incomes of $150,000 or more.”

For people who do not grow up participating in outdoor activities, going into the wilderness – which in British Columbia, is filled with bears and cougars – can be quite intimidating. It can also be dangerous for people who do not understand mountain safety.

But Instagram – which provides the exact location of trail heads and provides hiking tips to users – makes the outdoors more accessible. I recently overheard a woman on the St. Mark’s Summit Trail tell her friend that until a few years ago, she didn’t know these trails existed: She had assumed only avid outdoor folks with the right gear could do hikes. Instagram not only gave her information about where these trails were but also changed her vision about who could do them. While people may be discovering the outdoors because of Instagram, they are not necessarily going outdoors for Instagram.

Of course, Instagram is not lowering the prices of ski passes or the cost of outdoor gear – it is not changing the demographics of who lives in proximity to some of Canada’s most popular outdoor destinations. But in its own limited way, Instagram may be demystifying the outdoors.

The increase in outdoor tourism may also be a result of major infrastructure projects that have made the outdoors more available to people of varying physical abilities. The Sea to Sky Gondola in Squamish, built in 2014, for instance, was designed to accommodate wheelchair users. Before the gondola, the views from Mount Habrich could only be seen after a 7.5-kilometre hike. Now, people of varying ability levels can enjoy the jaw-dropping views of the Howe Sound. This summer, I visited Banff National Park and was impressed by how disability-friendly the park was: at Lake Louise, I watched two wheel-chair users race around the boardwalk along the shores of the glacier lake. Although many parks remain out of reach for people with disabilities, projects such as the Sea to Sky gondola provide an interesting example of how the outdoors could be made more accessible.

The Sea to Sky gondola has its own Instagram account. 'Weekends are for adventures with family and friends,' reads this post sharing a photo from user @iamgp360.Instagram (@seatoskygondola)

Increasing the accessibility of the outdoors and national parks to the Canadian public can have public-health benefits: It gets people outside, exercising and breathing in fresh air.

Many, such as the man behind the Public Lands Hate You account, argue that the increasing number of people visiting the outdoors will result in ecological damage. But as Joel Barde says in The Walrus, there are ways in which ecological damage can be mitigated, such as turning parks into “training ground for new hikers.” Having more people engage with the outdoors and gain a greater appreciation of nature could also be a powerful tool for getting people to care more about climate change and conservation.

Although there are many unanswered questions about how the increased number of outdoor visitors should be managed, the solution is not to judge new hikers for wanting to take photos. They too are able to recognize the beauty of a glacier lake and want to see it for their own eyes, and yes, get that forbidden selfie.

The increased popularity of the outdoors is not simply a superficial, Instagram-driven phenomenon. Sure, people may spend a lot of time taking photos. Maybe a small group of people are going outdoors with the sole goal of getting the perfect shot. But perhaps people are going outdoors because suddenly, it seems like they can.

Increasing the number of people that can access the outdoors and national parks should be part of our project of building a more equal Canada. In a young country such as Canada that is still looking to define itself, the outdoors – and our relationship to it – is seen as central to our cultural identity. One does not need to look far to find evidence of this. Until recently, our $5 bill depicted a group of people playing hockey on a pond rink. When I was last at the Calgary airport, a massive photograph depicted the back of a young, blonde woman as she paddled in one of Banff’s crystal blue glacier lakes.

Although many Canadians opt out of outdoor activities as a matter of preference, others are not given a chance to decide whether the outdoors will be part of their Canadian experience. Maybe Instagram is helping give them that choice.

Instagram (@_willoww)