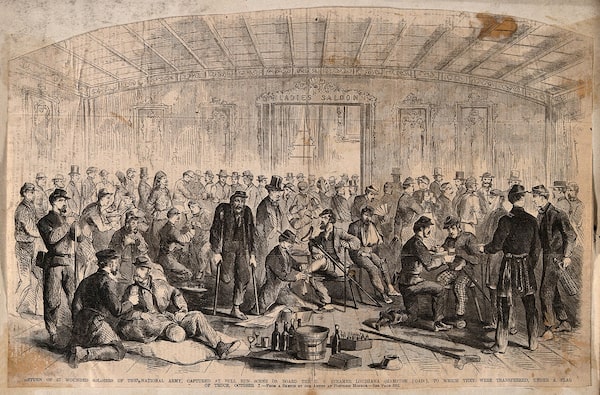

An artist's sketch from the American Civil War era shows 57 wounded Union soldiers being treated on board a steamer ship, the Louisiana, after their capture at Bull Run.Wellcome Collection

Brandy Schillace is the editor-in-chief of The BMJ’s Medical Humanities journal and the author of three books, most recently Mr. Humble and Dr. Butcher: A Monkey’s Head, the Pope’s Neuroscientist, and the Quest to Transplant the Soul.

The summer of 1862 baked under a stifling sun. The American Civil War raged on, Union and Confederate troops felling one another with the improved Minié muskets firing conical balls that shredded tissue on contact. In the span of four years, roughly 750,000 troops would die of wounds, infection, disease. Some lay for hours next to their fallen comrades, unable to reach medical attention. Others would be carried to disorganized field hospitals and stacked in makeshift beds in an indecipherable mass of human casualty.

Such chaotic scenes were hallmarks of battlefield medicine from Europe to North America. A new system was required, a way of sorting patients for admission. It would be practised at scale for the first time in August, 1862, by the medical director for the Union army. It would come to be called triage.

The word triage, at its most basic, means merely to sort. Originally from the French and first utilized during the Napoleonic wars (though not yet coined as such), the sorting of patients into groups meant treating those most seriously wounded first. But what if supplies ran short? Did it make sense to use precious materials on a soldier already bleeding out, in shock, or so grievously wounded as to be beyond saving?

At the First Battle of Bull Run, union surgeon C.C. Gray made a difficult decision: “We were obliged to select some [soldiers] for immediate removal as it seemed possible to save them,” he wrote. Under fire, against long odds, physicians began “the paralyzing task of sorting the dead and dying from those whose lives might be saved.”

Civil War medics would carry the wounded in Perot wagons like this one, shown at an exposition in Philadelphia in 1876.Wellcome Collection

Medicine had just taken on the task of deciding whose lives they would attempt to save — and who they would merely make as comfortable as possible on their way to death.

We tend to forgive historical record, and most of us would agree that battlefield medicine occasionally must make ugly choices. We think of Western civilian medicine as immune from such crises, but in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals face a catastrophe of unprecedented proportions.

COVID deaths worldwide have passed five million (by conservative estimate), with 250 million cases of the disease filling beds in hospitals and using up supply chains. While Canada has seen far fewer deaths – 29,000 by last count – there have been more than a million cases , and numbers were again on the rise at the end of summer.

Though rates have once again stabilized, the recent surges in Alberta and Saskatchewan, in particular, led to a scarcity of beds. Over the past 18 months, elective surgeries had to be cancelled and many continue to be pushed off by staff and supply shortages.

Medical professionals have engaged in the sorting of patients since the 1860s, but never have the stakes been so high. It’s little wonder that triage has triggered such powerful public response.

At top, a hand-painted stereo card (an early form of 3-D photograph shows wounded Union soldiers in 1862 at Savage's Station in Virginia. At bottom, medical staff monitor a patient in a triage tent in Martinique, a French overseas territory, this past August.James Gibson/U.S. Library of Congress; ALAIN JOCARD/AFP via Getty Images

“Death Panels” are coming, say the headlines (most recently from Idaho, both rural and COVID-stricken). The phrase was resuscitated (if not coined) by Sarah Palin, former Alaska governor and one-time vice-presidential hopeful, in an attack on government health care. She and other Republican party leaders claimed that teams of experts would decide who lived and who died -- just like in Canada. Canadian health officials quickly debunked the claim, which they rightly considered ludicrous.

Earlier this year, the grim spectre of death panels returned, this time in Quebec, after the release of COVID crisis protocols. Should ICU wards reach 200 per cent of their capacity, a team will be responsible for triaging incoming patients and determining who will be turned away. So far, Quebec has not enacted these measures, but we can foresee their possible outcomes already, in Starr County, Tex.

There is but one hospital in Starr County, serving a population of 64,000. In July, cases began a precipitous rise. “We are not ICU capable,” said Corando Rios, a nurse who became infected while treating patients, “but we are doing ICU work.” A county health board issued critical care guidelines to help health providers allocate scarce resources. It also recommended a committee for determining who has the best chance of survival — and who can go home to die.

No one wants to send their patients away, explained Jose Vasquez, a health official, but the hospital could not keep functioning otherwise; “the situation is desperate […] the numbers are staggering.” Beds, respirators and staff are simply insufficient to treat every case — and as the system clogs and breaks down, there are fewer resources for other emergency situations: a heart attack, a cancer screening, and even diabetic care are all potentially threatened.

The blame sometimes falls upon the care workers themselves, even nurses like Mr. Rios, quarantined in his home. “We are doing the best we can,” he said; the pandemic has created its own kind of battlefield medicine, its own kind of scarcity.

The province of Saskatchewan hosts more than one million people, and Saskatoon, with a population of 273,000, dwarfs Starr County. And yet, rural hospitals in Saskatchewan have been closing since before the year 2000. As part of its “wellness approach to health,” the Saskatchewan government in 1992 announced the closing and conversion of 52 small rural hospitals as part of a shift from “institutional care to community based care.” There are now only 81 hospitals total to treat a population of 1.17 million, one hospital for every 13,000 people, clustered around large city centres. As COVID numbers climbed in September and October, facilities could scarcely handle the sudden influx of sick and contagious patients. Triaging patients offers the means for organizing people and resources under these difficult circumstances, but as in Texas, extreme shortages may force doctors to make very difficult choices.

A COVID-19 ward at Starr County Memorial hospital in Rio Grande, Texas, shown in the summer of 2020. When the pandemic hit, this hospital was the only one in a county of 64,000.Christopher Lee/The New York Times

For Quebec’s crisis triage protocol, a committee including three physicians (at least one specialized in intensive care) and an ethicist decide your fate. They receive anonymous data about your condition. If you have only a very small chance of benefitting from ICU care, then you will rank lower than a patient with greater chances of recovery from the treatment. The outcome is not meant to put patients on the streets, but rather to remove them from advanced treatment hospitals to palliative care facilities. For severe cases of COVID, however, this is inevitably a death sentence. The multimember teams and anonymity supposedly ease the stress of the decision, but questions remain about whether or not civilian doctors should carry the burden of those decisions, especially when the criteria themselves remain subjective. As Eugene Bereza, a medical ethicist at McGill University, explains, “You’re asking [doctors] to do something that is contrary to what they believe in and are trained to do.”

The guidelines intend to exclude discrimination, to arrive at a fair assessment of a patient’s chances, and to sort them in a way that allows the most lives to be saved. And yet, problems remain. The criteria might ensure no decisions are based on race, ethnicity or financial security. At the same time, age — or “life cycle” — will be a factor. “What we’re saying,” says Dr. Bereza, is that those “who have had their life to live, so to speak, will be less prioritized than someone in their 20s, who haven’t had an opportunity to go through those life cycles.” Other considerations have to do with how long a patient might take to recover, prioritizing a “one week” stay over a “two month” stay to conserve beds in ICU. And though disability is not meant to be a factor, activists remind us of medicine’s history of determining disabled lives less worthy of saving. The American Association of People with Disabilities sent a letter to Senate majority and minority leaders at the very beginning of the pandemic, asking that Congress prohibit triage based upon “anticipated or demonstrated resource-intensity needs,” survival rates, or assumed quality of life. If triage suggests those with long-term care needs are less likely to receive intensive care, it already discriminates against those living with disabilities, and most especially those already using ventilators.

It might be appropriate in times of disaster “to delay non-essential care [and] not be obligated to provide quantitatively futile care” — but bioethicists from the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard, Bioethics Center of Colorado, O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law and others have pointed out that crisis triage arises only in “forced-choice scenarios,” when not everyone can receive care. “By permitting clinicians to discriminate against those who require more resources, perhaps more lives would be saved,” admits Ari Ne’eman, a disabled-rights activist, but the ranks of the survivors would by biased toward those without disabilities; “Equity would have been sacrificed in the name of efficiency.” Similarly, as patient-rights activist Paul Brunet recently said, Section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms of Canada could be interpreted to mean that ”everyone has the right to live and to be treated adequately in emergency situations.” The Quebec protocol is not yet necessary, they claim. It ought never to be necessary.

A Red Cross volunteer shows a doorway between beds at a mobile hospital in Montreal in April, 2020.Christinne Muschi/Reuters

Health providers use triage all the time; they must. The system devised on the battlefield has become today’s emergency room, a place for determining who must be seen immediately and who can wait for an hour until a doctor is available. Most of us have been on the receiving end, waiting in stark rooms for our turn (often complaining about how long it’s taking). Most of us have probably employed triage ourselves as parents or teachers sorting out which child is actually hurt from those who are crying along with them. Triage deserves our appreciation, for taking what once was a grisly, tumultuous and often futile attempt to save lives into our modern system of medicine; it has always been most concerned with giving and preserving lives. The greatest difficulties surrounding triage in the face of COVID has less to do with how and when its implementation arises, and more to do with its end goals. If all patients can be treated, it makes sense to treat them in the order most likely to save more lives. But if only some patients will be treated, then triage threatens to become a judgment. Which life is worth saving? “At its core,” writes Mr. Ne’eman, “these debates are about value” — the value of human lives.

Battlefield medicine had to make judgments about who to save and who to let perish, but this is not a war — and it’s not 1860. Physicians are civilians, not soldiers, and while modern medicine cannot save everyone, it has the opportunity to give everyone a fighting chance. Critics of COVID ICU triage rightly question the ethics and efficacy of any protocol that puts human lives at stake. It should be a last resort, preceded by equally unusual but less dire options, from bringing doctors out of retirement to giving provisional practising diplomas to nurses and therapists (also practised in the Civil War), to the building of temporary medical facilities (deployed during polio and flu pandemics). We have the privilege of great resources, even under pressure as they are, and we have the benefit of many years’ triage training for the purpose of saving lives. While we hope there will be no more surges, land borders have opened as of Nov. 9, and holiday travel is just beginning. We must ask ourselves how we can better handle the next crisis – whether from COVID or future epidemics – when, and not if, they come.

Front lines of the hard times

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Juno-winning musician Joel Plaskett performed a song about front-line health workers on a livestream with The Globe and Mail from his studio in Dartmouth, N.S. Take a listen.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.

Editor’s note: (Nov. 15, 2021): A previous version of this article suggested that Section 7 of the Canadian Charter said, "Everyone has the right to live and to be treated adequately in emergency situations.” In fact, that quote was an interpretation by patient advocate Paul Brunet. A previous version also stated that there have been more than a million hospitalizations in Canada; rather, there have been more than a million COVID cases.